Executive summary

There has been substantial interest in the person-centered care (PCC) model of nursing care. This model is characterized by patient or person sovereignty, in which the patient is the focus of care with their voice incorporated in decision-making and other healthcare processes. Patients and families play a significant role in determining actions, with the care plan reflecting the values and goals of the patient. This model is associated with improving the outcomes of

Respect for patient views, fast delivery of information, transparency, highly accessible care, well-coordinated care, collaboration, and prioritization of patient well-being are key attributes of the PCC model. This model leads to improved outcomes and quality of patient care. Other major benefits associated with the model include increased financial margins with reduced expenses, improved resource allocation, and higher productivity and morale among the staff.

The PCC model implementation makes a business case in mental health nursing. It is estimated that £2.5 trillion is incurred yearly on mental health and is projected to increase to £6 trillion by 2030.

In the hypothetical case, the program cost per patient per month is determined to be £300, with the program per patient per year being assumed to be £36000. The base utilization per patient per year is estimated to be £42,000, which will decline by an average of £17,000 per year if the new proposal is implemented. The service adaptation’s return on investment (ROI) will be 370%.

Background

Adopting a person-centered approach to community-based service and health care delivery is effective and appropriate for all groups of people. This model of care delivery is covered in international policies, practice recommendations, and national policies for its impact and capacity to improve the quality of care (Santana et al., 2021). However, patients with mental health illnesses are likely to receive the greatest immediate and long-term benefits from the adoption of this model, which is both holistic and collaborative. This case particularly exists since people with mental health illnesses have healthcare needs that are multi-faceted, diverse, and more costly than what the case is with other population groups.

According to health (2020), poor mental health is estimated to cost the world about £2.5 trillion annually and is projected to increase to £6 trillion by 2030. Similarly, Knapp and Wong (2020) provide valuable insights into the current and projected expenditures on mental health. As the researchers note, the world’s average expenditure on mental health care delivery is £2.5 per annually (Knapp & Wong, 2020). These expenditures on mental health care range from £0.1 to £21.7 per person depending on the region and only makeup only 2.0% of the global health expenditure. The meager investment in mental healthcare is one of the reasons for the gap between the needs in mental health and the delivery of interventions and poor outcomes.

In the UK, there is a case for increasing investments in mental health care. It is estimated that the cost of mental health to the economy is 117.9 billion each year (Knapp & Wong, 2020). These costs incurred in treating mental health and dealing with related outcomes take 5% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). Further, it is shown that about three quarters (72%) of the costs incurred are because of the loss of productivity among people with various types of mental health disorders, as well as the amount expended in paying for informal carers who play a huge role in availing the care and support for the persons with mental health problems.

Due to the scarcity of healthcare resources, there is a need to conduct economic analyses to optimize health and well-being. As Davidson et al. (2019) note, health and well-being maximization can be achieved through the use of effective and evidence-based approaches to decision-making, which can aid in identifying and deploying the best available resources. It is now almost obligatory to conduct economic evaluations when planning for a health service adaption or implementation of innovation. In the UK, there should be a formal cost-effectiveness evaluation and health technology or intervention appraisal to determine its effectiveness before implementation (Knapp & Wong, 2020). This paper focuses on adopting and implementing a patient-centered care (PCC) model in the care of people with mental illnesses.

Business Case Solution

The idea is to implement the PCC model in treating patients with mental illnesses. Key elements of the PCC model of care are that it promotes shared decision-making and active participation among providers, patients, and families in managing and treating conditions using a comprehensive and customized plan of care (Brickley et al., 2020). Key characteristics of this model are that values and mission are attuned to patient goals, family is welcome in the care setting, with family and the patient play a huge role in decision-making (Santana et al., 2021). The views of the patients and families are respected, there is fast delivery of information, transparency, and care is accessible, well-coordinated, and collaborative. Priority is given to the patient’s well-being. These elements of the PCC model lead to improved outcomes and quality of patient care. The major benefits of the model include increased financial margins with reduced expenses, improved resource allocation, and higher productivity and morale among the staff (Brickley et al., 2020). The model also leads to enhanced reputation and satisfaction scores.

According to health (2020), there is a strong investment and business case for investing in mental health. For every £1.0 invested in anxiety and depression treatment and management, there is a £4.0 return in terms of increased productivity and improved health. Thus, there is a need for high levels of collaboration and partnership among various stakeholders such as civil society organizations, the private sector, development banks, United Nations agencies, and academic institutions to invest, mobile, and disburse funds that will aid in mental healthcare transformation.

Several theoretical and empirical studies provide evidence that makes a case for investing in mental health care. Essentially, the failure to invest in robust and evidence-based strategies for prevention, health promotion, early intervention, and treatment can result in massive economic losses related to the need for social support, income assistance, and disability (Thorn et al., 2020). In addition, failing to invest in mental health can lead to high costs incurred due to high levels of morbidity and mortality and a decline in workforce participation that adversely affects the country’s GDP.

Chisholm et al. (2016) analyzed to determine the return on investment (ROI) of increasing the levels of investment in the treatment and prevention of anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders. Using projection modeling, the researchers looked at the effects of treating anxiety and depression, considering the economic outcomes of presenteeism, absenteeism, and returning to work. The study yielded a benefit-to-cost ratio of 2.3 and 3.0 to 3.3 and 5.7 for depression and anxiety, respectively. Similarly, Layard and Clark (2020) make a business case for treating mental health using Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), which costs an average of £650 per person. According to Layard and Clark (2020), the adoption of IAPT is “free,” and the government incurs nothing given that 1.0% of the working population relies on disability benefits due to depression and anxiety, which costs a minimum of £60 per person per month. Thus, based on this evidence, investing in treating mental health disorders can produce massive financial benefits in terms of savings.

A study by Brettschneider et al. (2020) provides evidence about the PCC model’s effectiveness in implementing cognitive behavior therapy in persons with depression and other common mental health illnesses. The study by Brettschneider et al. (2020) entailed a systematic review of 22 articles in which the researchers revealed that adopting the model resulted in incremental cost-utility ratios. In particular, Brettschneider et al. (2020) reveal that the implementation of CBT following the PCC model can lead to an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of between £1,599 and £46,206 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Studies have specifically highlighted the cost-effectiveness of the PPC model in different areas of care. For instance, Pirhonen et al. (2020) investigated PCC’s effectiveness. They have to have higher levels of cost-effectiveness from a 5-year and a 2-year perspective than usual care. In particular, using Monte Carlo simulation, the cost-effectiveness of PCC from a two-year perspective was between 80% and 99%, while that from the 5-year perspective was between 75% and 90% (Pirhonen et al., 2020). A study by Thorn et al. (2020) had similar findings as those by Pirhonen et al. (2020) regarding the cost-effectiveness of implementing PCC. In particular, the adoption of this model of care resulted in an £18,499 cost-effectiveness ratio, with 51% being cost-effective when considering a £20000/QALY willingness to pay threshold. Thus, considering the PCC is cost-effective and is shown to improve outcomes, it should be adopted and implemented.

Financial Plans

Pump Priming

In the hypothetical case, the program cost per patient per month is determined to be £300. Therefore, the program per patient per year is assumed to be £36000.

Ongoing Costs

The estimated baseline funding for the PCC is £42,000 per patient annually. These costs will be incurred in staffing and other activities related to normal learning in a healthcare facility. In particular, the costs will be incurred by nurses’ outpatient encounters with the patients and hospital admissions. The costs will entail expenditures on hospital readmissions, paying for hospital stays, emergency department (ED) services, and Skilled nursing facility (SNF) facility days.

Potential Returns/Savings

The impact of the new adaptation will be established by comparing the financial implications of the base and the new adaptation. The base utilization per patient per year is estimated to be £42,000. This amount is expected to decline by an average of £17,000 annually if the new proposal is implemented. Thus, the service adaptation’s return on investment (ROI) is 370%, which will be the return that will be realized from the integrated system. A summary of the returns from the initial case is summarized in Table 1.

| PCC’s cost per year per patient | ||

| Baseline utilization | ||

| Outpatient encounters | 12.2 | |

| Skilled nursing facility days | 7.0 | |

| Emergency department visits | 1.89 | |

| Hospital length of stay | 6.5 | |

| Hospital readmissions | 0.17 | |

| Hospital admissions | 1.33 | |

| Baseline costs | ||

| Hospital Stay | £3,500 | |

| Outpatient encounter | £125 | |

| Skilled Nursing Facility day | £300 | |

| Emergency department visit | £2,400 | |

| The overall cost for baseline utilization | ||

| Percentage changes because of PCC | ||

| Number of outpatient encounters | 0% | |

| Number of skilled nursing facility days | -20% | |

| Number of emergency department visit days | -10% | |

| Hospital length of stay | -10% | |

| Hospital cost per day | -10% | |

| Number of hospital readmissions | -33% | |

| Number of hospital admissions | -33% | |

| Overall utilization costs in post-PCC | £25,353 | |

| Cost savings | £16,933.00 | |

| Return on investment | 370% | |

The present PCC program will seek to increase efficiency (in terms of cost reduction) while enhancing the levels of program effectiveness, which is to lower the rates of hospital admission, readmission, and length of hospital stay. The program’s worthwhile returns will be realized by reducing the costs incurred per patient. Although diverse factors affect the return on investment, the program per person per month and admission rates are assumed to be the most influential factors. Table 1 shows the ROI variations for monthly patient costs and admission reduction rates.

| Program per patient per month | ||||

| Admission reduction | £500 | £400 | £300 | £200 |

| 40% | 211 | 288 | 418 | 677 |

| 30% | 170 | 237 | 350 | 575 |

| 20% | 129 | 186 | 282 | 473 |

| 20% | 88 | 135 | 214 | 371 |

Implementation and Evaluation Plans

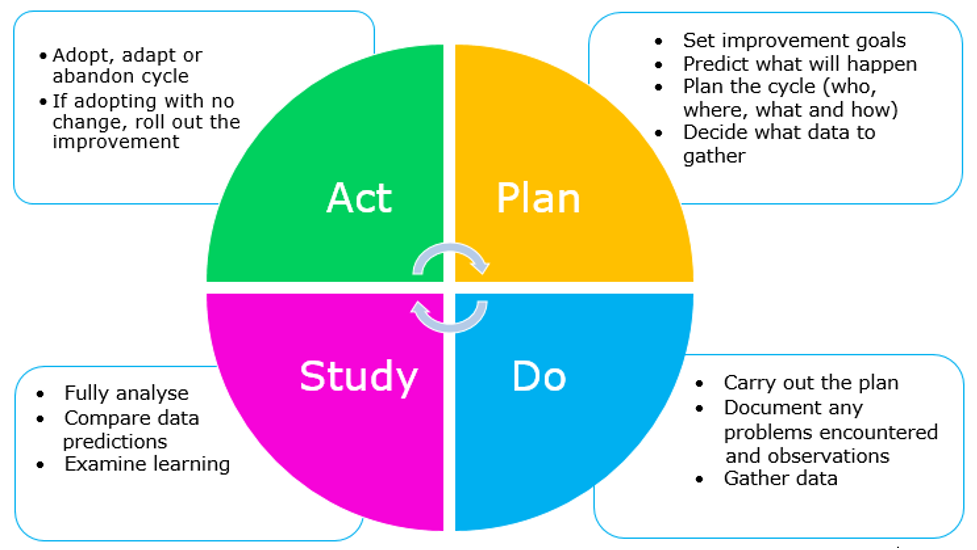

The implementation of the PCC model in the delivery of mental health care will be implemented following the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycle. This model is selected since it offers a highly effective approach to implementing change through the development and testing stages (Christoff et al., 2018). A key advantage of this model is that it helps overcome and repulse the risks associated with immediate action. Relying on the model will aid by encouraging testing out small improvements, building on the insights obtained from the small scale, before going for the large-scale implementation. Thus, adopting the model will give the stakeholders enough time to see the feasibility of the proposed change, making the change process less disruptive and safer for both the patients and clinicians.

In this case, the PDSA cycle will implement change and improve the existing care processes. Other key areas in which the PDSA cycle can be applied are that it plays an essential role in helping the project stakeholders understand what needs to be achieved and serves as a model for continuous improvement. Before embarking on the change or improvement process, it is required that one understands what one wants to achieve (the aim), how to evaluate and monitor progress, and what changes need to be made to realise the expected changes. In the present case, four steps will be followed in implementing the PCC model.

The first step’s focus will be clarifying the aim of the proposed changes and improvements. This project will be about adopting and implementing the PCC model of care in mental health care. Thus, the multidisciplinary team that will be involved in the care of patients will have to set measurable goals. Especially the goal that will need to be achieved is: introducing the PCC model to be used in at least 95% of patients with mental illness. This step will determine the approaches and methods of measuring change and evaluating the program. It is necessary to establish a robust strategy for determining whether improvement or change has occurred. The team will collect data about various variables, such as patient and clinical outcomes related to the impact of following the PCC model. Both qualitative and quantitative approaches to gathering, analyzing, and presenting data, such as questionnaires, interviews, statistical process control (SPC) charts, and run charts, will be used in the program evaluation.

In the second step of the cycle, the plan will be implemented, with the problems, successes, and opportunities recorded. Data collected and analyzed in this step will be used to abandon, adapt, or adopt the proposed change, done in the third step (S). Key activities that will be run in the third step entail describing what will have happened and how the results were measured. Lastly, in the fourth step (A), modifications and improvements for the subsequent phases will be made based on the results that will have been obtained.

Critical Reflection

Throughout the module and the entire nursing training, I have learned a lot and acquired important skills and competencies needed for nursing practice. The lectures, placements, service-based learning, assignments, and a diverse range of other opportunities offered me excellent learning opportunities.

Working in teams was another excellent experience I had throughout my nursing training. I can relate my experience to Tuchman’s group development stages, which entail forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning (Guttenberg, 2020). Each step had erratic behaviors, feelings, team, and needs. For instance, at any moment I worked together with other persons in teams, I realized that the start of the team building process was characterized by politeness, the need for safety, feelings of uncertainty, excitement, and optimism. This experience would change with team members tending to start arguing amongst themselves, as well as the feelings of increased tension, defensiveness, and resistance. However, everything would stabilize with all the members agreeing to work as a team. The experience I had working in teams helped me learn a lot of valuable insights about the role of leadership and management skills. It also helped me in the significance of teamwork and collaboration, especially in caring for people with mental health illnesses.

The entire nursing training and other experiences I had in specific modules helped me appreciate the role of teamwork. Teamwork in mental and overall nursing health care is crucial in improving patient care, safety, and outcomes (Sandelin et al., 2019). Mental health nursing faces myriad challenges, such as patients refusing medication, high levels of aggression, patients’ unpredictable behaviors, and the patients’ denial of the mental illness (Foster et al., 2019). This challenge makes nurses experience burnout, compassion fatigue, and other challenges that may lower the quality of care and patient safety. Through my experiences, I realized that having a robust and highly effective care team can help overcome these challenges. Some of the qualities of a highly effective care team are that it should have excellent change management, adaptability, effective communication, conflict resolution, and guidance or leadership and management skills. The team members I worked with had these qualities, which made the experience awesome.

Among the diverse skills needed for effective teamwork and mental health nursing, management, and leadership skills are particularly important. Some instrumental leadership and management skills a nurse needs are flexibility, integrity, strategic thinking, the ability to motivate others, delegation, emotional intelligence, conflict management, and effective communication (Sandelin et al., 2019). The experience I had helped me realise that I possess these qualities, which play a crucial role in helping me in working in teams. I also realized that I prefer transformational leadership, a leadership style inclined to cause a change in a social system or individuals (Goh et al., 2020). Making a case for and leading change, as is the case with the PCC model program, requires one to have transformational leadership skills. I also believe that laissez-faire, strategic, and democratic leadership styles can be crucial in ensuring successful teamwork and collaboration in mental health and general nursing practice.

Although I have learned and acquired many skills throughout my nursing training, I still need to work hard and take even more initiative in learning soft, technical, and technological skills that will enable me in my practice as a nurse. Leadership, effective communication skills, and relational skills are particularly instrumental skills that I will want to learn. I will use mentorship, self-learning, and attending seminars to learn and acquire various skills to enhance my competence and build capacity for nursing practice.

Reference List

Brettschneider, C., Djadran, H., Härter, M., Löwe, B., Riedel-Heller, S., & König, H. H. (2015). Cost-utility analyses of cognitive-behavioural therapy of depression: a systematic review. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 84(1), 6-21. https://doi.org/10.1159/000365150

Brickley, Bryce, Ishtar Sladdin, Lauren T. Williams, Mark Morgan, Alyson Ross, Kellie Trigger, and Lauren Ball. “A new model of patient-centred care for general practitioners: results of an integrative review.” Family Practice 37, no. 2 (2020): 154–172. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmz063

Chisholm, D., Sweeny, K., Sheehan, P., Rasmussen, B., Smit, F., Cuijpers, P., & Saxena, S. (2016). Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(5), 415-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30024-4

Christoff, P. (2018). Running PDSA cycles. Current problems in pediatric and adolescent health care, 48(8), 198-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2018.08.006

Davidson, L. (Ed.). (2019). The Routledge handbook of international development, mental health and well-being. Routledge.

Foster, K., Roche, M., Delgado, C., Cuzzillo, C., Giandinoto, J. A., & Furness, T. (2019). Resilience and mental health nursing: An integrative review of international literature. International journal of mental health nursing, 28(1), 71-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12548

Goh, P. Q. L., Ser, T. F., Cooper, S., Cheng, L. J., & Liaw, S. Y. (2020). Nursing teamwork in general ward settings: A mixed‐methods exploratory study among enrolled and registered nurses. Journal of clinical nursing, 29(19-20), pp. 3802–3811. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15410

Guttenberg, J. L. (2020). Group development model and Lean Six Sigma project team outcomes. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLSS-09-2018-0101

Health, T. L. G. (2020). Mental health matters. The Lancet. Global Health, 8(11), e1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30432-0

Knapp, M., & Wong, G. (2020). Economics and mental health: the current scenario. World Psychiatry, 19(1), 3-14.

Layard, R., & Clark, D. M. (2015). Why more psychological therapy would cost nothing. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1713.

Pirhonen, L., Gyllensten, H., Fors, A., & Bolin, K. (2020). Modelling the cost-effectiveness of person-centred care for patients with the acute coronary syndrome. The European Journal of Health Economics, 21, 1317-1327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01230-8

Sandelin, A., Kalman, S., & Gustafsson, B. Å. (2019). Prerequisites for safe intraoperative nursing care and teamwork—A qualitative interview study: operating theatre nurses’ perspectives. Journal of clinical nursing, 28(13-14), 2635-2643. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14850

Santana, M. J., Ahmed, S., Lorenzetti, D., Jolley, R. J., Manalili, K., Zelinsky, S., … & Lu, M. (2019). Measuring patient-centred system performance: a scoping review of patient-centred care quality indicators. BMJ open, 9(1), e023596. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023596

Thorn, J., Man, M. S., Chaplin, K., Bower, P., Brookes, S., Gaunt, D., … & Salisbury, C. (2020). Cost-effectiveness of a patient-centred approach to managing multimorbidity in primary care: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ open, 10(1), e030110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030110

Wharaurau. (n.d.). Plan do study act cycle (PDSA) [Video]. Whāraurau. https://wharaurau.org.nz/quality-improvement/pdsa

write

write