Piracy is the looting, theft or confiscation of property in the maritime waters and the practice of attacking and robbing ships at sea. Many elements have contributed to the rise of maritime piracy internationally and in the Netherlands. The threat posed by pirates on the high seas is no stranger to the maritime industry. In addition to stealing goods, it is known that pirates kidnap crew members to demand a huge ransom. A safe marine environment is essential for the smooth flow of world trade and for maintaining international peace and security. Pirates, kidnappings and armed robbery all pose a direct threat to merchant ships and crew members, leading to transnational crimes at sea. Maritime piracy also includes organised crime groups to trade arms, drugs and kidnapping sailors for ransom. International companies have long argued that poverty and unemployment in coastal groups are the root causes of piracy, excessive world trade and restrictions on world trade. Other causes of maritime piracy maritime capacity, the acquisition of social status, social support and corruption, and the presence of armed groups, (Cantino et al., 2017). This includes the coastal lines and marine vessels in Southeast Asia, the Gulf of Guinea, the Gulf of Aden, Latin America and the Caribbean. An overall assessment of the root causes of piracy can be summarised in the root financial causes and the root social causes. The basic reasons for maritime piracy can be excessive revenue opportunities, very low flight costs, very low opportunity costs and financial risk. The main social causes of piracy are the maritime potential and traditions of the region, the possibility of acquiring social status through piracy, the occurrence of complaints and the existence of public support for piracy (Chaix, 2017). In addition, the political causes of piracy in the seas and sea lanes include corruption within the state, as in the case of West Africa and Nigeria, which has a high presence of armed groups, low state capacity, and has vast regional disputes.

Poverty among the coastal communities is a major cause of maritime piracy. As a result, piracy in Southeast Asia encompasses a diverse group of people, methods, and motivations. Poverty, unemployment, poor infrastructure, and state isolation have left the local population exposed to the effects of environmental degradation, conflicts, overfishing, and economic crises, all of which are regarded to be contributing to the growth in piracy. As a result of the maritime traditions developed in the region, many fishers turned to piracy as a means of livelihood. Pirate gangs, both organised and unorganised, are popular in the area; however, they typically recruit unemployed youths and desperate men with a varied variety of targets made possible by closeness to shipping routes and overfishing restrictions and market access made possible by ties to organised fishing (Collins, 2016).

Government corruption neglects coastal communities. For example, in the Gulf of Guinea and on the coasts of West Africa, communities are poor and complain about piracy, institutional corruption, inequality and environmental degradation inherent in the system. It is accepted that this is the principal driver of theft in the area. Martin Murphy stated that the Niger Delta is snacked because political performers and their employees have taken a great deal of their oil overflow and left too little for the people. As a result, pirate gangs and rebels often attack foreign tankers and platforms for fuel purposes. Despite the economic impact, society generally supports this activity, especially because illegal actors spend money on government support (Dahalan et al., 2010). As such, these attacks are seen as an attempt to remedy some of the inequalities caused by corruption due to the massive public protests against the oil industry.

The piracy in the Gulf of Guinea is natural piracy caused by poverty and unemployment first emerged among the poor in Nigeria’s coastal and port security community. Because the state failed to stop this activity, piracy became more organised and a growing threat to the large commercial shipments in and out of the country. The existence of pirates is tolerated in many societies, as a series of complaints about the country’s income inequality, persistent corruption and disastrous oil industry which has been major causes of maritime piracy (Trouillet et al., 2019). Young people are drawn to these gangs for many reasons, including promises of money, power and status. Corruption, organised crime and links with insurgent organisations open the door to organised robberies in the market, making it a very simple business model for development. In particular, allegations of corruption are a form of political protection under the rule of law. To date, the national deterrence efforts have generally failed, or piracy has spread to other vulnerable areas of the country, highlighting the need for greater regional cooperation (De-Buitrago, & Schneider, 2020).

Pirates of the Gulf of Aden result from a combination of misfortune and opportunity. On the other hand, toxic destruction and anger from poaching are the main drivers of piracy. On the other hand, Somali piracy goes beyond that initial statement as organised piracy groups thrive in a state of decay, and the rule of law is completely absent. Due to limited economic prospects, especially among young people, unemployed fishers and former police officers, promises of welfare and social status are rarely kept. This economic model based on frustration and greed is now well organised, with coastal regions, local economies, corrupt officials, and financial firms playing an active role in sustaining this process. This will undoubtedly be a major challenge for international stakeholders investing in sustainable, long-term solutions to Somali piracy.

Piracy off the coast of Somalia began in the early 1990s and may be related to the collapse of the Barre administration (Denton & Harris, 2022). The country’s systematic business model involving stakeholders from all disciplines has matured, and the mandatory software is now around $200 million, making it the second-largest source of revenue in the country, with only broadcasts from the Somali diaspora.

Cladynamics also plays a very important cause in piracy in the Gulf of Aden, particularly on the Somali coast. Tribal dynamics also play a role in these relationships. Pirate groups were also organised according to loyalty and clan hierarchies as important determinants of population size (Hagmann, 2016). The majority of Puntland’s officers are from the same Majirteen sub-clan main pirate group in the region. Although not directly involved in these activities, these officers could benefit from distributing the ransom money among clan networks (Tominaga, 2018). This dynamic adds another layer of complexity to the coexistence of avoidance and condition, making it difficult to eradicate the connection between them.

The economic benefits of piracy are another factor that drives maritime piracy worldwide. The economic benefits of piracy to local communities are also disputed. The Oceans Beyond Piracy report found that the growth of the local pirate economy was accompanied by sharp increases in inflation for basic goods, gasoline and housing. However, they acknowledge the difficulty of distinguishing between the specific effects of piracy and other prosecutions in Somalia. In contrast, the Chatham House study found that rice prices in local markets in Somalia fell due to piracy (Hasan & Hassan, 2016). On the contrary, the report found that the benefits of piracy are mostly felt in district capitals and other urban areas suspected of sponsoring such attacks, compared to coastal communities participating in such activities. Satellite imagery of the growth and development of the community illustrates this investment in downtown piracy. Despite these conflicting views, the relationship between pirate gangs and society needs to be better understood to find a solution against ground piracy.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, coastal unemployment and high levels of corruption are the main causes of piracy. Corruption, which is widespread in Latin America and the Caribbean, is another factor that could contribute to the spread of piracy in the future. Although there is a documented link between the two, criminal activity usually thrives under some of the most corrupt governments in the region. In Venezuela, for example, crime was rampant under Hugo Chavez. Domestic crime had increased from 4,550 in 1998, when Chávez was elected, to 19,113 in 2009. According to the Latin Barometer survey, 64% of Venezuelans cited crime as the most important problem the country has to solve, the largest number of countries surveyed.

Piracy is also associated with taking pride in controlling a coastal area or territory. The merchant ship Naviluck, for example, was assaulted by three boats packed with men in early 1991, a few miles off the Somali coast, who slaughtered members of the ship’s crew, set her on fire, and sunk it. The terrorists did not attempt to steal goods, kidnap hostages, or demand a ransom. Coastal people, who are typically hostile to foreign ships, are more inclined to take matters into their own hands.

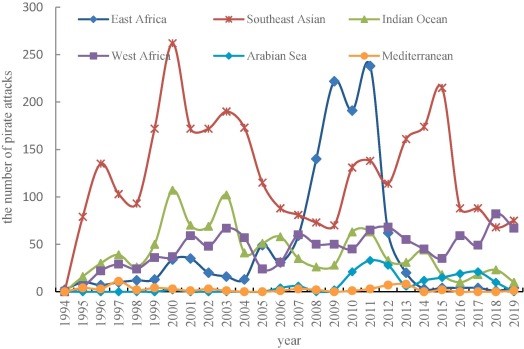

Figure 1; The analysis of maritime piracy occurred in Southeast Asia by using Bayesian network – Science Direct

These organized hacking hotspots change frequently. This is because these bands are attracted to low-cost areas. Therefore, their area of responsibility changes when “the police increase patrols, arrest gangsters, move pirates to more profitable waters, or stop their activities altogether. These changes often correspond to a local trigger. For example, between 1993 and 1995, piracy flourished in the HLH triangle between Hong Kong, Luzon and Hainan. This was due to the interference of Chinese port authorities. Pristrom et al. (2019) argue that piracy, like smuggling and corruption, can be an unofficial source of income for the military and law enforcement.

In conclusion, pirates, hijackings and armed robberies directly threaten merchant ships and their crew, leading to international crime at sea. Maritime piracy also includes organized crime groups that trade in arms and drugs and kidnap sailors. International companies have long argued that poverty and unemployment in coastal groups are the main causes of piracy, excessive world trade and world trade restrictions. Other reasons include maritime capacity, social status, social support and the presence of corruption and armed groups. The root causes of piracy can be excessive revenue opportunities, very low flight costs, very low alternative costs and financial risks. The basic reasons for maritime piracy can be excessive revenue opportunities, very low flight costs, very low opportunity costs and financial risk. The social causes of piracy include maritime potential and regional traditions, the possibility of gaining social status through piracy, dissatisfaction and public support for piracy. Moreover, the political causes of piracy at sea and transportation routes include internal state corruption, as in West Africa and Nigeria.

References

Cantino, V., Devalle, A., Cortese, D., Ricciardi, F., & Longo, M. (2017). Place-based network organizations and embedded entrepreneurial learning: Emerging paths to sustainability. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research.

Chaix, S. (2017). Beyond Catch and Release: An Analysis of the EU Naval Force’s Disruption and Deterrence of Somalian Piracy. Available at SSRN 3221447.

Collins, V. E. (2016). Somali pirates: victims or perpetrators or both?. In Towards a Victimology of State Crime (pp. 80-100). Routledge.

Dahalan, W. S. A. W., Kisahi, A. B., Sevanathan, S., & Nasir, M. (2020). The Challenges of Prosecuting Maritime Pirates. Sriwijaya Law Review, 4(2), 221-237.

De-Buitrago, S. R., & Schneider, P. (2020). Ocean Governance and Hybridity: Dynamics in the Arctic, the Indian Ocean, and the Mediterranean Sea. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 26(1), 154-175.

Denton, G. L., & Harris, J. R. (2022). Maritime piracy, military capacity, and institutions in the Gulf of Guinea. Terrorism and political violence, 34(1), 1-27.

Hagmann, T. (2016). Stabilization, extraversion and political settlements in Somalia. Nairobi: Rift Valley Institute.

Hasan, S. M., & Hassan, D. (2016). Current arrangements to combat piracy in the Gulf of Guinea Region: an evaluation. J. Mar. L. & Com., 47, 171.

Pristrom, S., Yang, Z., Wang, J., & Yan, X. (2016). A novel flexible model for piracy and robbery assessment of merchant ship operations. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 155, 196-211.

Tominaga, Y. (2018). Exploring the economic motivation of maritime piracy. Defence and peace economics, 29(4), 383-406.

Trouillet, B., Bellanger-Husi, L., El Ghaziri, A., Lamberts, C., Plissonneau, E., & Rollo, N. (2019). More than maps: Providing an alternative for fisheries and fishers in marine spatial planning. Ocean & Coastal Management, 173, 90-103.

write

write