Introduction

In ancient Greece, there were around one thousand city-states. Still, the most essential polis was Athina (Athens), Kórinthos (Corinth), Sparti (Sparta), Thiva (Thebes), Égina (Aegina), Siracusa (Syracuse), Argos, Ródos (Rhodes), Erétria, and Elis (National Geographic Society 3). Each city-state was in charge of its own affairs. When it came to governing philosophies and interests, they were diametrically opposed to one another. At the time of the fall of Sparta, it was ruled by two kings as well as an earlier council. It put a high value on maintaining a strong military, while Athens placed a high value on education and the arts. Every male citizen in Athens had the right to vote, which resulted in a democratically elected administration. Rather of fielding a huge army, Athens chose to keep its fleet (National Geographic Society 3).

The article presents a historical account of Athens as one of the ancient Greek cities. It emphasizes its position, characteristics, and urban history. Additionally, the page provides maps and illustrations illustrating the city’s relative position and its interior structure at various eras. The approach employed in this study is employing relevant scientific sources to substantiate the facts and assertions.

Athens City Site

Athens, Greece’s capital and most significant city, is primarily acknowledged as Europe’s oldest capital city, having been a functional town for 5,000 years. Athens was named for the goddess of learning and warfare. It is still one of Greece’s most important cities, featuring UNESCO World Heritage sites and historic structures such as the Parthenon. In the first millennium B.C., Athens was one of Ancient Greece’s most important towns and the world’s earliest named city. According to (Platt 6), the city lies in Southern Europe, and it is well-known for its cultural accomplishments in the 5th century B.C., which laid the groundwork for modern civilization. It was Greece’s most influential and biggest state capital. The Greater Athens region is 165 square miles (427 square km). On the European continent, Athens is situated in Greece at 37.98 latitudes and 23.72 longitudes. The city is situated on the rocky slopes of Acropolis, which served as a natural defensive position in ancient times (Vanderpool and Ehrlich 3).

The city of Athenian City was located about 20 kilometres from the Saronic Gulf, in the heart of the Cephisician plain, a lush country surrounded by rivers. Mount Hymettus lies on the city’s east side, while Mount Pentelicus is on the north side. Furthermore, the city is located in the Attic lowlands of the Greek mainland, surrounded on three sides by mountains. Mount Parnis, Pendeli, and Hymettus are the most significant. Beautiful public baths and construction stores may be found in Agora, Athens’ social and economic centre, situated approximately 400 meters north of the Acropolis. Aside from that, Athens has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate. The city’s climate is compounded by the neighbouring mountains, which induce temperature inversion.

Figure 1: The position of Athens in ancient Greece 500 BC

Features of the City

When approaching from the Middle East, Athens is the first European city, with its big buildings and modern businesses. The East’s impact on the food, music, and raucous street culture is striking whether entering Athens from the west or elsewhere in Europe, according to (Vanderpool and Ehrlich 5). However, it is incorrect to suggest that Athens is a combination of East and West: it is Greek, and more specifically, Athenian. After all, it was the city that gave birth to Western civilization thousands of years ago. To this day, Athens is still a significant player on the international scene.

Both natural and artificial marvels distinguish the city of Athens. Around 400 B.C., Athens was founded. People who lived in the region created monuments and structures still standing today during its long history. As reported by (History.com Editors), the Parthenon is one of Athens’ most well-known Greek buildings. The Parthenon is situated on the Acropolis, a hill that provides a panoramic view of the city. In Greek mythology, the Parthenon was built in honour of Athena, the goddess of battle and wisdom. The Athenian Acropolis utilized the Parthenon as a temple and a site of devotion, with images and colossal sculptures of Athena wearing full gold armour. The Parthenon is a unique edifice in Athens since it was erected after the triumph of Athens against the Persians in 480 B.C (History.com Editors). It is a symbol of democracy. The structure was constructed to honour Athens’ cultural, economic, and political prowess. Construction of the Parthenon began in 447 BCE and was completed in 438 BCE.

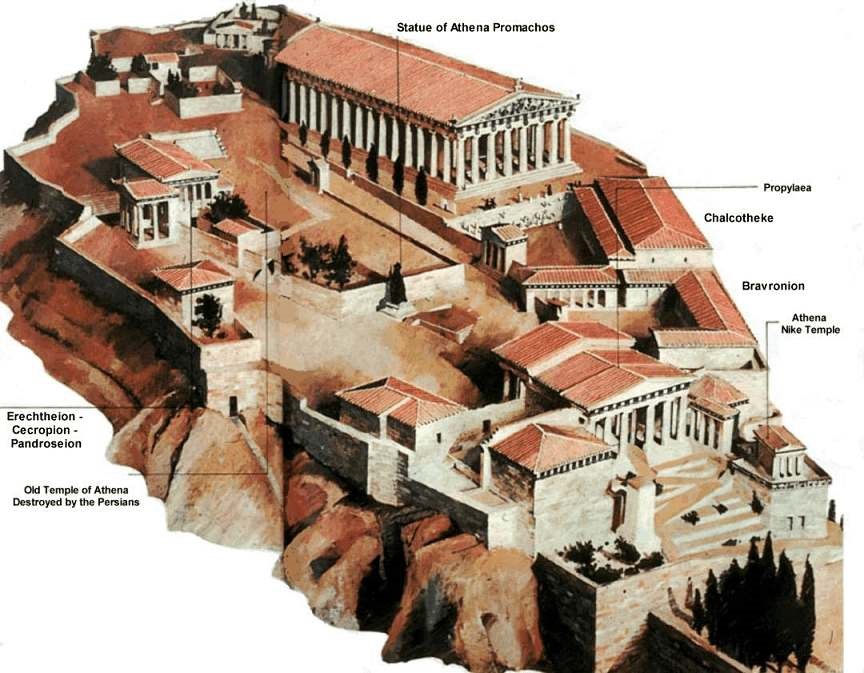

The Acropolis is another noteworthy landmark of the city of Athens. The name Acropolis derives from the Greek word Acropolis, which means “edge city.” The Acropolis of Athens is the most renowned of the several Acropolises that mark Greece’s cities. Athens’ Acropolis was constructed in the second part of the fifth-century B.C.E (Ehrlich). The structure was built on a high point and was often utilized as a site of defence and sanctuary from the enemy during wartime. The Acropolis of Athens was built on rocky land at the summit of a hill. There were ruins of various old structures, which are historically and architecturally significant. Although the Acropolis and the Parthenon seem identical, the fundamental distinction between the two structures is that the Acropolis is the hill on which the Parthenon temple is constructed. As a result, Acropolis refers to the hill, whereas Parthenon refers to the ancient structure. According to (Ehrlich), during the building of the Acropolis, the Athenian government had many enslaved people who contributed significantly to the workforce. The Acropolis is well-known for its many historical significance. For example, the tower served as a royal residence, a fortification, a religious centre, a legendary dwelling for the gods, and a tourist attraction, all of which contributed to its fame in Athens.

Figure 2: Ancient Buildings on the Acropolis

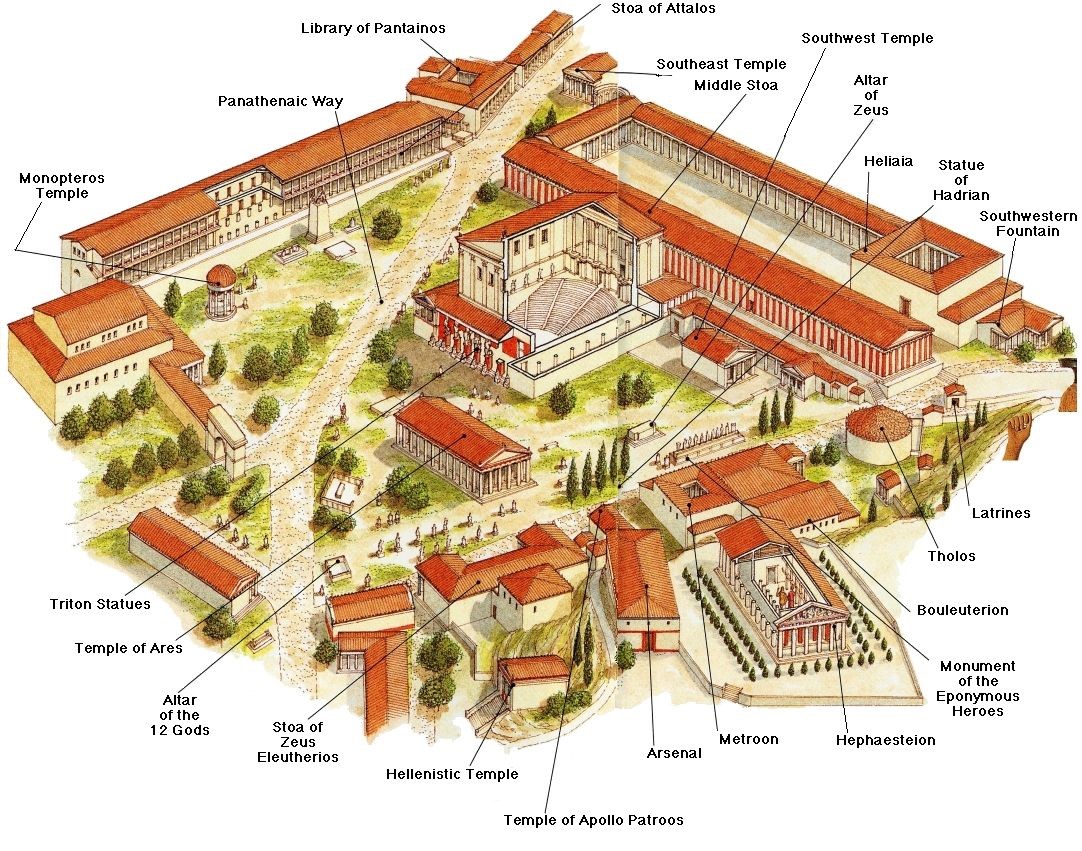

The Agora, often known as “the Ancient Agora of Athens,” is another important landmark of Athens. The word Agora refers to a “public meeting area.” The Ancient Agora was a centrally positioned public community in Athens that hosted all types of public activity (Ehrlich). The public area served as a gathering place for the community to debate philosophical, political, and other forms of public events. As a result, the Agora played an essential role in developing constructive ideas in Athens society. However, during the 6th and 1st centuries B.C.E., Agora had an essential role in the city, serving as a forum for public discussion, a market, a site of worship, and the court and the centre of the government. Because of the free thoughts and conversations about the community’s political elements, the Agora supported democracy in Athens (Ehrlich).

Figure 3: Overview of Athenian Agora

Ancient Athens’s Urban History

Urbanization, which comprises architectural history, urban geology, commercial history, social history, and urban sociology, defines Athens’ historical nature. Between 3500 and 3200 B.C., ancient Athens engulfed a small region of around 2km from west to east. The city’s early occupants built huts at Olympeion and on the South and North slants of the Acropolis, which were utilized as hiding places during enemy attacks and wars (Cohen 90). People in the city utilized caverns as safe-havens, while the hills allowed them to track down foes from afar. The hills, which served as hiding places and provided spring water to the residents, was the fundamental cause for the permanent settlement in Athens. The communities were sparsely inhabited and spread out throughout Acropolis’ south and north slopes. During this time, Mycenaean society was headed by a powerful ruler named ‘Wanax,’ whose palace was built on a cliff (Palaima).

Later, from 1050 to 700 B.C., Athens suffered the downfall of Mycenaean civilization due to a chaotic and evil era that resulted in depopulation (Khan Academy 5). Athens recovered and began marching west of the Acropolis to the Nymphs’ Hills. While the Kingship rule was abolished, the communities were merged under a single political authority. The old structures and shrines were destroyed when Persians set fire to them. The Athenians restored the city and reclaimed their dominance after victory against the Persians. They built circular buildings and thirteen gates that encircled the whole hamlet. The wall separated the Karameikos into two districts: the inner and outer Karameikos (Mirkovic 150). The erection of the demolished wall bolstered the people’s defence.

However, between 323 and 86 B.C., Athens lost her political power but retained its cultural and aesthetic qualities, earning it the title “Hellenistic Athens.” The city was altered by capable monarchs like Eumenes II and Attolos, who ordered it via methodical urban design, clearly separating social sections from open spaces (Khan Academy 10). The Romans ruled the city of Athens. After the Hellenistic period, the Romans awarded Athens various advantages, including the city’s designation as a distinguished cultural city under Athens’s authority (Mirkovic 149). Athens attempted to overthrow the Romans, but Sulla, a Roman general, punished them severely. The Athenians were left helpless once the Romans invaded the city, out of limits for Roman opponents. The city was subsequently restored by Roman emperors, such as Emperor Augustus. He erected a new market that provided merchants and artists space for workshops and stores to sell their wares.

Following the fall of the Roman government, the Byzantine period rose to power, allowing the city to continue regular activities and thrive as an intellectual hub. Like the Tetraconch in Hadrian, the earliest Christian churches were built in the fifth century, and religion thrived (Jarus). The cultural and economic life of Athens, on the other hand, was devastated mainly by Emperor Justinian, who outlawed philosophical schools. Later, the city grew into villages under Latin administration, which lasted more than two centuries. During this reign, the Frankish Tower, the city’s tallest building, and the Belvedere were built (Jarus).

The Ottoman Empire arose following the fall of the Roman Empire. It impacted the social development of ancient Athens, despite the absence of traditional division patterns in the city. Although the Albanian and Greek orthodox populations outnumbered the Muslim population, a large proportion of Turks lived in the central area, as shown by several mosques (Cohen 86). The boundaries between social and urban regions were not based on religion allowed Christians to rent Muslim inhabitants’ houses, enabling Muslims and non-Muslims to dwell peacefully together in the city. During the conflict between the Venetians and the Ottomans, the ancient monuments and the wall that encompassed the city were destroyed. However, the city developed and was split into eight districts due to this expansion. For lack of cemeteries in the city at the time, the Greeks were buried in churchyards, while the Muslims were buried in the vicinity of mosque complexes. Additionally, since the land use was not defined, workshops, graves, and houses were thrown together in one location.

Before the start of the Greek War in 1821, Athens had grown to a population of almost 10,000 people, making it the most populous city in Central Greece (Cohen 87). Despite being chosen as the Greek State capital, the city was devastated during the conflict. The new Athens emerged under the influence of Romanticism, merging ancient heritage with the European city. By 1880, the city’s population had increased, and infrastructure improvements had been made. Water supply, roadway asphalting, the Attica Railways, and lighting were all part of the significant infrastructure at the time. Roman and neoclassical architectural styles were used in Athens’ structures. When Athens was designated as the Greek state capital, several unlawful structures were built. The Anafiotika and Proastio villages, for example, were compelled by population growth and the presence of peasants. The ancient Greeks of Athens were master architects, as shown by ancient structures such as the Parthenon are still standing after centuries.

Figure 4: After the ancient ages, the morphology of Athens

Conclusion

In conclusion, the development of the city of Athens was aided by a variety of circumstances, including its geographic location and the presence of democratic institutions in the city. For example, the city was built on rocky hills that served as defensive areas where the Athenians could hide from their enemies’ attacks; as a result, the city was considered protective during times of warfare. There were open spaces in the city where all public concerns could be debated, and as a consequence, democracy was a prominent practice in the city, resulting in outstanding leadership. With the several governments that existed in ancient Greece, Athens was among the oldest and most important cities in Europe throughout the first millennium. The Parthenon, the Acropolis, and the Agora were only a few of the stunning natural and constructed structures that distinguished the city. Beginning in antiquity and continuing through industrialization, the city of Athens has seen substantial transformation and expansion. Consider, for example, how the city underwent substantial changes in architecture, economy, social, and urban history that led to its evolution. In addition, the city placed high importance on cultural accomplishments, which helped to contribute to the city’s rapid development.

Work Cited

Cohen, Elizabeth. “Explosions and Expulsions in Ottoman Athens: A Heritage Perspective on the Temple of Olympian Zeus.” International Journal of Islamic Architecture, vol. 7, no. 1, 1 Mar. 2018, pp. 85–106, 10.1386/ijia.7.1.85_1. Accessed 22 Feb. 2020.

Ehrlich, Blake. “Athens – the Acropolis | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2020, www.britannica.com/place/Athens/The-Acropolis.

History.com Editors. “Parthenon.” HISTORY, A&E Television Networks, 2 Feb. 2018, www.history.com/topics/ancient-greece/parthenon.

Jarus, Owen. “History of the Byzantine Empire (Byzantium).” Live Science, Live Science, 21 Dec. 2013, www.livescience.com/42158-history-of-the-byzantine-empire.html.

Khan Academy. “Ancient Greece, an Introduction.” Khan Academy, 2016, www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/greek-art/beginners-guide-greece/a/ancient-Greece-an-introduction.

Mirkovic, Alexander. “Who Owns Athens? Urban Planning and the Struggle for Identity in Neo-Classical Athens (1832-1843).” Cuadernos de Historia Contemporánea, vol. 34, 2012, pp. 147–158, revistas.ucm.es/index.php/CHCO/article/download/40066/38495.

National Geographic Society. “Greek City-States.” National Geographic Society, National Geographic Society, 15 Mar. 2019, www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/greek-city-states/.

Palaima, Thomas G. “The Nature of the Mycenaean Wanax: Non-Indo-European Origins and Priestly Functions.” Repositories.lib.utexas.edu, Université de Liège, Histoire de l’ art et archéologie de la Grèce antique; University of Texas at Austin, Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory, 1995, hdl.handle.net/2152/63630. Accessed 7 Mar. 2022.

Platt, Josephine. “A History Lesson on Europe’s Oldest Cities.” Culture Trip, 11 May 2020, theculturetrip.com/Europe/articles/a-history-lesson-in-Europe’s-oldest-cities/. Accessed 7 Mar. 2022.

Vanderpool, Eugene, and Blake Ehrlich. “Athens | History, Facts, & Points of Interest.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 17 Aug. 2018, www.britannica.com/place/Athens.

write

write