Traditionally, broadcast and print media have provided materials that impact how audience forges their identities, including gender, class, sexuality, and distinction between us and them. Specifically, the media images influence how people view their world and the values they cherish. Stories that emanate from the different media products create resources and symbols through which people make a common culture and sub-culture (Nyarko, 2022:3). A critical analysis of the specific sub-culture in the media is an exciting topic of this essay, mainly how media influence the emergence of the Riot Grrrl subculture movement. The portrayal of the Riot Grrrl in magazines/newspapers will be particularly interesting in the essay because it seeks to analyze the representation of this sub-culture and its stereotypes. As Downes (2012) explains, the emergence of punk culture provided women with a cultural space to transgress sexual and gender hegemony. Nevertheless, the punk culture that gave prominence to male performers undermined women’s contribution. The Riot Grrrl emerged in reaction to women’s marginalization, suppression, and alienation in the media/punk music culture (Downes, 2012). However, the reception and perception were not rosy in the patriarchal society. Indeed, society perceived the subculture as deviant because it failed to accept women’s exclusion in punk music and the group’s focus on taboo topics. As Downes (2012) explains, the music produced by the group was branded negatively because it challenged the existing gender stereotypes. Often, the media framed the subculture as dangerous and scary (Downes, 2012). This aligns with the moral panic by Cohen and peers in which the media and journalists identify aberrant behaviours and mobilize concerns (Walsh, 2020: 841). Consequently, this paper will analyze how the mainstream newspaper represented Riot Grrrl in relation to mobilizing society’s concerns about the queer sub-culture as a threat to the dominant societal values.

Newspaper articles about Riot Grrrl were non-existent before the 1990s when the subculture emerged in response to the exclusion in the punk music scene. As Dunn and Farnsworth (2012) explain, punk emerged in the 1970s with reference to the music scene in the US. It describes several bands, including Voidoids, Ramones, and Richard Hell, among others. However, punk music gained global attention after it emerged in the UK. The antics of the punk music style borrowed heavily from the predecessor subcultures such as rockability, rude boys, and skinheads (Dunn and Farnsworth, 2012: 137). In addition, punk music was conditioned by the dominant class politics and thus served to mock the crumbling of the UK society. It quickly spread throughout the world. It reflected particular diversity because it did not reflect the male gender, as was the case with rock music. Instead, punk music emphasized diversity with respect to males and females. In 1977, it was commonplace to see females playing bass, which was a complete break from the rock. But after years, punk culture, as with other subcultures, was influenced by patriarchal tendencies and values, and this became unfriendly to women, especially on the West Coast, where all-male bands like Black Flag were preoccupied with expressing masculine punk energy (Dunn and Farnsworth, 2012: 137). Ultimately, the punk music culture became anti-women with the violence. Indeed, extant literature indicates that women ceased going to punk bands because of violence. Eventually, women found themselves pushed to the periphery of the punk music culture. In the 1990s, frustrated women formed the Riot Grrrl movement in collaboration with their feelings from Olympia and Washington, DC, who were drained of having their voices silenced by the all-male punk music culture (Wright, 2016:53).

As a group established separate from the punk subculture dominated by males, the Riot Grrrl rebelled against patriarchy in society. Rather than resigning to the prevailing societal trend where women became unseen, the group of like-minded women formed their sub-culture fueled by their representation in the media or male-centric punk music scene. Allison Wolf, Kathleen Hanna, and Molly Neumann founded Riot Grrrl to challenge normative ideas, sexism, and misogynistic tendencies found in the punk culture. As the subset of the feminist movement, the Riot Grrrl movement also sought to speak up against oppressive societal values such as telling girls they are weak and dumb. Thus, the Riot Grrrl subculture challenged conventional beliefs about girls and femininity. Since most of the founders had initially been members of the punk music subculture, which was known to use performance as a protest tool, the Riot Girl saw music as a powerful avenue to express themselves on various issues, including sexuality, rape, abortion, domestic violence, and body image that had been represented differently by the mainstream media (Wright, 2016:53). In their musical composition, the Riot Grrrl thematizes issues and struggles in the society while encouraging their audience to take an active role in women affairs. For example, the “Rebel Girl” song by the group encourages women to catalyze gender revolution (Wright, 2016:54).

Once its ideas began to spread and become popular, mainstream magazines and newspapers showed interest in covering Riot Grrrl stories. However, the mainstream newspapers’ representation was in negative light. As Ingram (2015:3) explains, the Riot Grrrl felt that the mainstream newspapers ignored their individuality and group motivations were simply reduced to fashion statements, nothing else. For example, a 1992 article published by USA Today described Riot Grrrl simply as female fans clad in Pucci-print minis (Ingram, 2015: 3). In another article published by USA Today, the journalist said it was horrified by a group of punk girls who she considered unintelligible (Mantila, 2009: 5). The journalist went ahead to describe their appearance as awful, aggressive, and bossy behaviour that threatened her. A close reading of the USA Today news article indicates that the journalist is biased. She did not seek to interrogate what the Riot Grrrl was doing but only focused on their bossy behaviour and unintelligibility. It is simply a crude generalization of the Riot Grrrl subculture designed to horrify readers the same she is horrified (Mantila, 2009: 5). This negative portrayal of the Riot Grrrl group sought to create the perception that the group threatened the societal values and this needed taming. This representation ignores that while the Riot Grrrl subculture emerged from punk music, they were not punk girls; it was about supporting all girls.

Additionally, the Riot Grrrl used music as the medium for sharing and voicing their concerns and issues. From the outset, the Riot Grrrl used their music to voice their concerns about taboo topics such as women’s empowerment, as illustrated by the song “Double Dare Ya“, which asked listeners to become or do what they wanted (Mantila, 2009:5). In response, such songs, the group faced increased mainstream media scrutiny with biased news coverage. As illustrated by the USA Today article, the mainstream news articles distributed damaging misinformation intending to discredit the Riot Grrrl and trivialize their ideas by calling them screaming brats using names such as the slut to market their bodies (Mantra, 2009: 6). The realization of the danger posed by the mainstream media, the Riot Grrrl said it could not allow other people or newspapers dominate their images.

The rejection of how the mainstream represented them was informed by the independent Do-it-yourself values inspired by second-wave feminism, which meant using other means of communication. In other words, the Riot Grrrl was not uninterested in hearing the mainstream newspapers about what the group represented or was doing. Consequently, the group embraced self-representation to make themselves visible to society without relying on the mainstream media that trivialized them as angry girls and revolutionary girls who threatened society (Schilt, 2003: 6). The Riot Grrrl fear was based on the understanding that in the era of mass consumption, the media produced products for audience. Accordingly, the Riot Grrrl felt the need to regain control of their representation from the mainstream media. Thus, the alternative form of communication became critical to Riot Grrrl in expressing their ideas as captured by their goals. According to their manifesto, the group emphasized the importance of creating content in their publications or fanzines that could allow girls to feel included and make their meanings (Dunn and Farnsworth, 2012: 141). Specifically, the Riot Grrrl emphasized the need to control their means of production to make their meanings and confront the status quo that trivializes, ignores, chokes, silences, stereotypes, and invalidates women/girls (Dunn and Farnsworth, 2012; Wright, 2016).

Consequently, the group embraced the do-it-yourself ethos that was popular with punk members, transforming them from mass media consumers to cultural production agents (Dunn and Farnsworth, 2012: 144). The Riot Grrrl subculture used fanzines to tell stories ignored or overlooked by the mainstream newspapers. In fact, the fanzines provided a vital space for the members to freely express ideas of their subculture and discuss issues of rape, exclusion, harassment, sexism, and other experiences. It allowed them to control how they presented ideas and representations to the world. For the Riot Grrrl subculture, to whom doing away from the misrepresentation and stereotypes about their belief was of most significant importance, fanzines only ensured their voice was heard without being corrupted by the mainstream media. In fact, the subculture advocated for media blackout to prevent inaccurate representation of their belief and values by the mainstream media (Wright, 2016: 55).

Despite Riot Grrrl’s effort on the Do-it-yourself ethos of second-wave feminist media production, mainstream journalists continued to pay attention to their activities. Extant literature suggests that since 1992, several mainstream news articles, including Newsweek and Rolling Stone, have focused on group activities (Dunn and Farnsworth, 2012: 141). However, it is argued that the coverage of Riot Grrrl in these mainstream news articles negatively impacted the movement, with some representing them as preposterous girls parading around with only innerwear. The mainstream news articles often failed to conduct serious interviews with Riot Grrrl members. Instead, the journalists used the information from the fanzines and misreported it. Some Riot Grrrl’s members underscore this point; for example, Kathleen Hanna maintained that while the group wrote about sexual abuse, the media never reported such (Dunn and Farnsworth, 2012: 142).

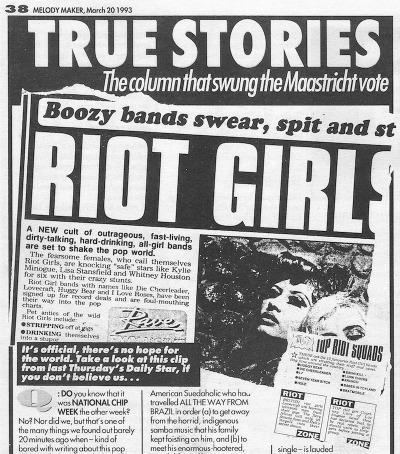

Consequently, the representation of the Riot Grrrl subculture in the mainstream newspaper/press is critical to assess in this essay to determine whether it was negative or positive. The need to decide the Riot Grrrl representation in the mainstream press is founded on the rationale that this subculture, as defined by Hebdige (1979; 3), threatened the dominant culture as a resistance object. Therefore, it is expected that Riot Grrrl would be met with intense disapproval by the mainstream press that represented the dominant culture. Taking this notion into consideration, the first image from the mainstream press that will be considered for analysis is the Melody Maker, 20 March 1993 article. The image of some Riot Grrrl members in black and white features a headline that describes the group as a bossy band that spits. The Melody Maker, that represented the dominant culture, captured the features of subcultural rebellion in the group by describing the movement as “A new cult of outrageous, fast-living, dirty-talking, hard-drinking, all-girl bands are set to shake the pop world”(Melody Maker, 1990). This stereotypical description of the Riot Grrrl exaggerates their alleged misbehaviour, such as talking dirty and binge drinking. It seeks to represent them as mindlessly and dangerously rebelling against the subculture. The Melody Maker claims that the Riot Grrrl group foul-mouthed their way into the pop chart using antics such as excessive drinking and stripping off at the performance.

Figure 1: Melody Maker (1990)

As with the several mainstream presses of that time, the girls pictured in black and white colours are portrayed as rebellious to the mainstream culture. One must admit that the Riot Grrrl rebelled against the dominant society and used music to convey their ideas, which were received negatively by the media, which represented the dominant culture. This explains why the mainstream newspapers, as seen in Figure, 1labeled them promiscuous and dangerous to society. Batt (2014:59) underscores this point by noting that the ideas Riot Grrrl represented were seen as a threat to capitalism and society. The ideology that challenged the status quo was a threat to the mainstream media, which depended on status for its existence and functioning. Therefore, stereotyping Riot Grrrl subculture as the idea to be feared by newspaper readers was an effective way for the mainstream press to prevent others from engaging themselves with the Riot Grrrl (Batt, 2014: 59). Similarly, stereotypical representation of the Riot Grrrl members as promiscuous by stating that they stripped of the gigs substantiates the conception of them as the danger to the society. The objective is to enable society to shrug them aside, thereby rendering their campaign/challenge to the dominant culture ineffective because no one would be involved in them beyond what the mass media reported about them. Historical accounts suggest that the decision by the mainstream media was informed by the decision by the Riot Grrrl to reject overtures from the mainstream media and fashion moguls who had sought to utilize the revolutionary spirit of the girls in the subculture that had become popular (Batt, 2014:60). For example, when Kathleen Hanna and Bikini refused the to offer Spin Magazine interview opportunity, the journalists who represented the mainstream media embarked on the campaign to turn the entire Riot Grrrl into a subculture with negative connotation as seen in figure 1 to dent the validity of the group message and activities.

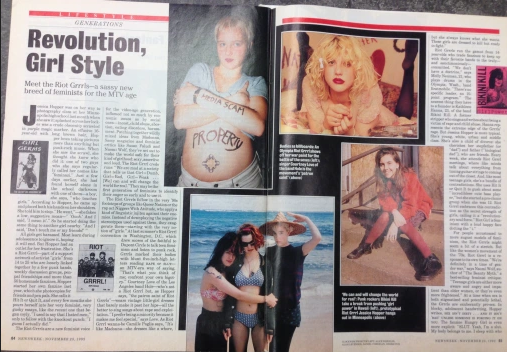

It can be argued that the mainstream media and culture could not reach Riot Grrrl leaders like Kathleen Hanna, who had given the press a blackout. Hence, the mainstream formulated their ideologies of the subculture as deviants, as illustrated by the figure below from the Newsweek article titled “Revolution, Girl style” (Chideya, 1992). It is said that, like other mainstream media journalists, Chideya faced challenges reaching out to Kathleen Hanna. Still, shockingly, she wrote the article quoting Kathleen in a lengthy interview with Jessica Hopper, who she described as one of the Riot Grrrl activist girls connected together by the punk bands and fanzines. According to Chideya (1992), the Riot Grrrl was a feminist group inflamed by social issues such as harassment and incest and sought to ensure the world was safe for assertive and sexy girls. The article feature scantily dressed members of the Riot Grrrl, which the members supposedly use to sing about issues such as rape. This might be inaccurate because it was based on the journalist’s ideology rather than the comprehensive interview with Riot Grrrl leaders and members. Shockingly, Chideya describes Hanna as the former stripper who wrote and sang on issues of issues related to rape. She portrays Hanna as representing the extreme rage of their subculture, while Hopper is a moderate white girl who respects both his biological father and stepfather. Here, Hopper seems to neutralize the threat posed by Riot Grrrl leaders like Kathleen Hanna. Chideya concludes the article by whipping emotions about the threat Riot Grrrl poses, even to President Clinton’s daughter, if she moves to Washington. She might also become a member of the subculture too.

Figure 2: Newsweek (1992)

The second image from the Newspaper article shows that despite Riot Grrrl’s effort to block media coverage, it is interesting that some mainstream newspapers represented the subculture. As explained by Hebdige, once the popular press discovers a subculture, the ideological form is labelled as deviant (Jacques, 2001: 46). The ideological threat or moral panic that mainstream media create about the subculture is neutralizing or trivializing it or transforming it into meaningless exotica (Jacques, 2001: 46). In figure 1, the mainstream media sought to trivialize threat posed by Riot Grrrl subculture by referring them to group white and middle-class girls such as Hopper. The threat posed by Kathleen Hanna, the Riot Grrrl leader trivialized by representing her as a former stripper who focused on child abuse and rape (Chideya, 1992). This trivialization of the Riot Grrrl subculture as a group of misguided youth explains why the group resisted mainstream media. Members of the subculture condemned the mainstream press for its unacceptable representation of girls for uncharacteristic femaleness.

In conclusion, the Riot Grrrl subculture that young girls founded, fed up with the exclusion of the punk music subculture, as well as sexism in the dominant society, has been discussed. Using their punk music knowledge, the young girls used music lyrics and Do-it-yourself values to voice concerns over issues such as body image, sexual abuse, and rape, among others. Mostly, the subculture was dominated by white middle-class girls who, right from the outset, decided to resist the mainstream press. Despite the effort to resist media through the participatory culture and Do-it-yourself publishing through fanzines, the mainstream press continued to pay attention to Riot Grrrl activities. In line with the Hebdige conceptualization of subculture, once the mainstream press discovered Riot Grrrl subculture in the ideological form, it moved to label it as deviant, outrageous behaviour by the white girls. As seen in Figure 1, the mainstream press alarmingly represented Riot Grrrl as a threat to the traditional culture because it involved promiscuous girls who stripped off for gigs and engaged in binge drinking. This aligns with Cohen’s idea of moral panic that media create by manipulating the threat posed by the subculture to the dominant culture. This was the case with Riot Grrrl, who threatened the dominant culture represented by the media. In addition to creating moral panic, the mainstream press dealt with the ideological threat posed by the Riot Grrrl by trivializing the threat that the subculture posed to the dominant culture. For example, figure 1 shows how the journalist described Hopper as a moderate white middle-class girl with a warm relationship with her biological and stepfather. This description sought to transform the subculture into a meaningless spectacle of the young white girls. In other words, the mainstream media neutralized the difference between the subculture and the dominant culture.

References

Batt, A. (2014). Bubblegum girls need not apply: Deviate women the punk scene. The Undergraduate Journal of the Athena Center for Leadership Studies at Barnard College, 2(1), pp. 52-62.

Buckingham, D. (2007). Riot Grrrl meets the media: Recuperation and resistance. Available at: https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/real-girl-power-representing-riot-grrrl/riot-grrrl-meets-the-media-recuperation-and-resistance/. Accessed 16 March 2024.

Chideya, F. (1992). Revolution, girl style. Newsweek. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/revolution-girl-style-196998. Accessed 16 March 2024.

Downes, Julia (2012). The expansion of punk rock: riot grrrl challenges to gender power relations in British indie music subcultures. Women’s Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 41(2) pp. 204–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/00497878.2012.636572.

Dunn, K. and Farnsworth, M. S. (2012). We are the revolution: Riot Grrrl press, girl empowerment, and the DIY self-publishing. Women Studies, 41, pp. 136-157. DOI: 10.1080/00497878.2012.636334.

Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The meaning of style. London: Routledge.

Ingram, S. (2015). Riot Grrrl zines and online magazines: a study of the self-publishing used by feminists 1990-2015. The Journal of Publishing Culture, 4(1), 1-9.

Jacques, A. (2001). You can run, but you can’t hide: The incorporation of Riot Grrrl into mainstream culture. Canadian Women Studies, pp. 46-50.

Mantila, S. (2019). Ugly girls on stage: Riot Grrrl reflected through misrepresentations. University of VAASA, Available at: https://www.butler.edu/academics/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2022/01/communication_studies_by_kate_siegfried.pdf. Accessed 16 March 2024.

Melody Maker (1993). Riot Girls. Available at: https://www.tumblr.com/plasticplant7/83015005574/riot-girls-a-new-cult-of-outrageous-fast-living. Accessed 16 March 2024.

Nyarko, J. A. (2022). Culture and media technology evolution. SSRN. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4209642. Accessed 16 March 2024.

Schilt, K. (2003). A little too ironic: The appropriation and packaging of riot Grrrl politics by mainstream female musicians. Popular Music and Society, 26(1), pp. 5-16.

Walsh, J. P. (2020). Social media and moral panics: Assessing the effects of technological change on societal reaction. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(6), pp. 840-859. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877920912257.

Wright, L. (2016). Do-it-yourself girl power: An examination of the Riot Grrrl subculture. James Madison Undergraduate Research Journal, 3(1), pp. 52-56.

write

write