Abstract

This project studies the possibilities of alternative consumption models, notably rentals, resale, and sharing, in developing a more aware and ecological attitude to fashion consumption. The primary question is whether these techniques can reduce the environmental impact of rapid fashion, shift societal attitudes toward clothing ownership, and provide economically viable alternatives. The study investigates essential topics related to sustainable fashion practices using a mixed-methods approach that includes a thorough literature analysis and primary research methods such as surveys and interviews. The literature review explores scholarly publications, including works by Kawamura and others, to identify such issues as rapid fashion’s environmental consequences, consumerism’s psychological effects, and new collaborative consumption models. Primary data interpretation entails examining survey responses and interview insights to investigate consumer awareness, sharing attitudes, and economic factors. Incorporating secondary sources contextualizes preliminary findings, resulting in a holistic comprehension of the modern fashion world. This study’s findings reflect a critical synthesis of observations, focusing on the consequences for the fashion business and sustainable consumer behaviors. Logical and reasoned recommendations go beyond mere ideas, addressing the intricate interactions of environmental, social, and economic issues. The research intends to add to the ongoing discussion about rethinking fashion consumption by advocating a paradigm shift toward more thoughtful and sustainable fashion clothing use. The report is accompanied by visual graphics, improving the conveyance of essential themes while maintaining a professional presentation level.

Contents

Introduction

The environmental and ethical effects of fashion consumption have become serious concerns in an era of fast fashion trends and the industry’s constant expansion. “Can Rentals, Resale, and Sharing Promote More Mindful, Sustainable Use of Fashion Clothing?” is the research topic this study sets out to investigate. This investigation was spurred by the pressing need to confront the environmental harm caused by rapid fashion and the expanding understanding of the socioeconomic factors associated with fashion ownership. The main goal of this study is to determine whether rental, resale, and sharing modes of consumption act as catalysts to promote a more conscientious and ecological approach to fashion. This inquiry explores the potential for shifting the direction of fashion consumption toward long-term socially and economically sustainable behaviors in addition to ecologically mindful ones. The main concerns regarding the environmental effects of rapid fashion are at the center of this inquiry. Three major issues that need to be addressed immediately are the excessive use of natural resources, the production’s carbon footprint, and the buildup of textile waste. Crucial components of the research also include the societal ramifications of individual fashion item ownership and the financial sustainability of alternative consumption models.

The field of sustainable fashion practices, which aims to balance the need for environmental preservation with the never-ending desire for new trends, is larger than the study done here. The fashion industry is going through a paradigm change toward more ethical and responsible practices despite being frequently attacked for its part in contributing to exploitation and pollution. In light of this, investigating substitute consumption patterns becomes essential to conceiving a more sustainable future for the fashion industry. A mixed-methods strategy addresses the complex components of the research subject. The research uses secondary research techniques like a rigorous literature review, enhanced by Kawamura’s insights and other academic works, to develop a thorough grasp of the theoretical terrain. Supporting quotes taken from Kawamura and other influential theorists will justify the responsive research methodologies employed by this study. The survey research method will be employed to capture the perspectives of key stakeholders like environmental activists, industry experts, and the needs. This allows for a deeper understanding of the views relating to fashion consumption and the feasibility of personally substituting models. An ethical approach was undertaken throughout the research, ensuring respect for participants’ rights and privacy. The following sections interpret the data and analysis from secondary and primary research, thus offering a comprehensive overview of the potential held within clothing rentals, resale, and sharing toward facilitating more mindful and sustainable fashion clothing consumption.

Literature Review

The contemporary fashion business is in a critical state, being forced to rethink strategies to address evident environmental and social commitments. This literature study examines the ever-evolving subject of sustainable fashion consumption, particularly rentals, resale, and sharing. Over the past years, the fashion industry has undergone a remarkable transformation as consumers, professionals, and industry leaders have started to agree that fashion must be consumed more responsibly. The contemporary fashion business model is in crisis due to growing concerns about environmental sustainability and ethical responsibility.

As the environmentally detrimental effects of fast fashion are becoming increasingly apparent and ecological footprints increase, as well as ethical controversies take on much more significance, a reevaluation of current models is needed. In order to suggest sustainable alternatives for fashion consumption, themes and common issues will be grouped to provide insight from academic publications. This literature review aims to comprehensively understand the different opportunities and issues surrounding sustainable fashion consumption by critically analyzing a wide range of articles.

Renting, selling, and sharing clothes are sustainable examples that fight back against traditional consumer practices. As fashion and identity suggest, this paradigm shift involves ecological and highly complex psychological dimensions. Economic dimensions and possibilities for collaborative consumption to change society are also researched in this literature review, which draws from academic sources to give a good overview of the specific dimensions the fashion industry is already living.

Evolution of Sustainable Fashion

Concerns of ecology and ethical implications of the traditional fashion industry, led by fast fashion, have resulted in sustainable fashion as an alternative to fast fashion strategies. The fashion industry has moved from a relatively linear and more stable fashion consumption pattern to fast fashion.

The process was a linear production, consumption, and disposal model. This is often referred to as fast fashion, under broad ethical problems and environmental degradation, said Kusá et al. (2020). The rapid production rate leads to increased pollution while also increasing the use of natural resources by an unsustainably large amount of textile waste, according to Kusá et al. (2020). People similar to Kusá et al. (2020) have been why people today know about how wasteful of resources the short fashion trend is and how harmful it is to the environment and the people.

A change of image! It is not in vogue when thinking eco-friendly. However, there is an upward shift of consciousness regarding ethics and the environment. Those fighting it out and encouraging viable alternatives to the current environmental mess that the fashion world heavily contributes to, from consumers and activists to industry insiders. Similarly, sustainability has become cooler than one specialized discussion. Friendlier environmental responsibilities, fairer ethically produced clothing, and mindful consumerism with a cyclical approach are your keys to sustainably prioritized. Eco-materials, sustainable processes, honest labor, and waste reduction. All are building up a fashion career in environmentally friendly brands and projects, working to build a better, fairer, and more sustainable future.

Brands and designers are already starting to put long-life and ethical considerations first and have a mindset of sustainability built into their ethos; this means sustainable fashion is not just a fad but a systematic change that starts with challenging the dominant theories of traditional fashion Kusá et al. (2020),. Sustainable fashion was initially assumed to be confined to niche markets; however, now, because of consumer demands for accountability, transparency, and environmental options globally. Thanks to technological breakthroughs, sustainable fashion has been launched and is just emerging again due to greener practices. Improvements have aided these practices in materials science, manufacturing techniques, and supply chain management.

The fashion industry’s transition to sustainability is a dynamic and continuous process. It has achieved several advances, but several problems of ignorance still exist. It needs to obtain support and constant innovation to find the proper balancing point between sustainable practices and the necessities of a consumer-driven market. The catchword of sustainable fashion is a commitment to rethinking the relationship between producers, customers, and the environment to make the world more ethical. In other words, the fashion industry is heading towards a dramatic shift involving considerably more responsibility and honest business.

Fast Fashion and Its Environmental Impact

Fast fashion, defined by its short production calendar, low-cost apparel, and fast-changing trends, has become a popular topic in the conversation about sustainable fashion. This section provides information from classic case studies and more recent research and dives into the environmental impact of the fast fashion trend.

Like everything around us, fast fashion destroys the environment when creating these products. With mass production as another name for fast fashion, it requires a lot of natural resources, primarily electricity and water. Focusing on mass production, it points out how it affects the water supply and is highly energy-intensive to get things done (Niinimäki et al., 2020). Furthermore, because so many clothes are being made, dyeing and finishing causes water pollution, which harms the local communities and the ecosystems.

Furthermore, a considerable amount of waste is generated due to rapid production. According to Jacometti (2019), the fashion industry sends significant amounts of clothes to landfills after just a few years. The landfill issue is one thing this highlights, but it also shows how resources are wasted when constructing garments with such short life spans. In the long run, the fast fashion industry’s linear- ‘take, make, dispose’- approach is too costly business-wise and for the rest of the environment.

A further important consideration in the fast fashion environmental cost is the delivery of goods contributing to carbon emissions and the carbon footprint. The industry is international, meaning that we produce the clothing in one region and wear it in another, which requires a lot of shipping and transportation. A significant contribution to climate change is increased greenhouse gases. Academics and environmentalists believe we will soon need a more localized and sustainable approach to fashion manufacturing and delivery to reduce these environmental impacts.

In addition, chemicals are used in various textile production processes, including dyeing and finishing operations. Thousands of recognized hazardous chemical substances threaten human health and the constituents of the primary environment. Discharging chemicals into bodies of water harms the organisms that reside in the water and can damage the ecosystems that the water leads to. Therefore, academics advise the fashion industry to meet the various chemical management standards and advocate for the industry to reform the production process to make it consistent with environmental safety.

Fast fashion affects the environment negatively: the chemicals that seep into the surroundings whenever they are used during production, the carbon emissions, the production of waste, and the use of resources. Researchers express that it is imperative to mitigate these effects if sustainable fashion business is the intent and five as quickly as possible. Different models that can be an alternative to fast fashion to limit the damage it causes to the environment are renting, reselling, and sharing.

Psychological Dynamics of Fashion Ownership

Fashion ownership is critical to understanding consumers’ psychology and determining their motivation and behavior. Works by scholars in recent years have considered the intricate relationship between the person, the clothes she wore, and what society expects from her. Effectual attachment to clothes presented some interesting points of view: by emphasizing the concept of \textit{“extended self”}, an idea of the type of clothes able to be an integral part of who people were, Maxey (2022) stressed the relevance of clothing respect of personal identity: this productive, as well as not only standardly functional, bonding is a typical attitude that merely represents a person’s memories, goals and a general sense.

Maxey’s theory of fashion psychology (2022) investigates the impact of different social surroundings on consumer behavior. The complex “social identity” process through clothes, personal interests, sociocultural concepts, fashion trends, and the necessity for social approval dictate people’s choices of what to wear.

Consumer decision-making in fashion is closely tied to one’s perception of social status and self-worth. In fashion ownership, the appeal to be oneself and establish a sense of belonging is enormous. Furthermore, the recent sociocultural emphasis on individualism and inclusiveness has made these interactions all the more complex.

In the era of social media, people are a part of the fashion story, not just the consumer. How a person presents himself on sites such as Pinterest or Instagram enhances the psychological ownership in fashion, where the “ideal self” given online is mainly linked to fashion aspirational choices. This encourages constant purchasing because it creates an identity that needs to be visually pleasing and socially validated.

It is critical to consider the mental ramifications of fast fashion and how that influences a person’s state of being. The Maya Society of Today piece contemplated how turbo-trends influence people to be unhappy and expectant of a constant bombardment of new objects. People often waver internally about the lasting effects of buying something—balancing the environmental implications of their fashion choices with the need to express themselves.

This portion discusses the way fashion shapes individual and collective identities. This shows how psychology influences a consumer to care for their claim of fashion. This breaks under sharing, renting, and model resale and discusses psychology and sustainable fashion practices by looking at potential current educational efforts.

Collaborative Consumption Models

Besides the conventional consumption pattern, people are more likely to practice collaborative consumption, also known as the sharing economy. Collaborative consumption can support ecological principles, which are currently widely recognized. The definition of collaborative consumption is available in Arrigo (2019). It refers to the shift from ‘ownership focused to one of utilization and access.’ It has shown that garment libraries, peer-to-peer sharing platforms, and shared wardrobes are the new alternatives to traditional shopping. In this part, we will look at the introduction of collaborative consumption, including how it formed, how effective it is, and the challenges faced while executing.

Thrift stores, such as thredUP and Depop, have become haunted spots of the fashion industry. The resale market thrives because secondhand goods can last longer than the new ones purchased, which causes a long-lasting and more environmentally friendly solution to the fast-fashion disposable beast. Arrigo (2019) states that due to an increased awareness of the impacts of clothing production on the environment, there will be a considerably general interest in secondhand shopping.

Renting is another noble motive of collaborative consumption. Many companies, such as Rent the Runway, allow customers to rent clothes for a fraction of the price for wear on only one occasion. This method saves the need to have an abundance of wardrobe pieces. Rental subscriptions are beginning to rise for that exact reason, especially in this climate of upgrading tastes. The consumer no longer has to lease an outfit and spend too much on shipping it back. It is as simple as choosing which clothes a user likes, paying the monthly fee, and voila, there is a new set of clothes in their possession.

Nonetheless, these models of cooperation imply great efforts. One major obstacle is that consumers’ mentalities are deeply attached to traditional concepts of “ownership.” The strength of the Second Hand VICE or sharing platforms is significantly limited by the negative connotation associated with secondhand clothes or people’s resistance to sharing personal goods. The mental resistance can only be reasonably overcome by changing the perception of pre-owned and shared fashion products through adequate communication targeted toward awareness.

Additionally, another significant component in the picture of successful collaborative consumption is which models make economic sense. Collaborative consumption must be mindful of financial and environmental feasibility so that, as much as possible, it aims to be sustainable. In this vein, businesses must overcome challenges such as maintaining inventory logistics for rental services or quality control for used goods.

The prolonged focus on collaborative consumption by the fashion industry signifies a broader cultural shift towards more conscientious consumption. The more this conversation happens, the more it reinforces the need for businesses, governments, and consumers to enact change to create a more sustainable future. The changes collaborative consumption can bring to how we relate to ownership and engage with fashion can take a crucial role in tamping down our rampant purchasing behaviors.

Economic Viability of Sustainable Fashion

The financial implications of adopting sustainable fashion practices have become evident in the industry to both stakeholders and consumers. Academic publications and business studies will be explored in this section to understand the financial repercussions of renting, selling, and sharing.

Most people think of sustainable fashion as an investment in the health of the industry and of the environment in the long term. According to Ray and Nayak’s (2023) research, fashion companies can save money and run more efficiently by becoming more sustainable. These firms can become economically sustainable by making their production processes more streamlined and reducing waste, their environmental impact, and the resources they use.

A positive aspect of using resale platforms is profitability. Bakkenist and Lammers’ (2021) research on resale programs claims that the secondhand market has dramatically increased because of applications like Depop and The RealReal. Furthermore, used clothing is rapidly gaining popularity as more consumers understand the financial value of preowned items (Bakkenist & Lammers, 2021). This allows clothing manufacturers to use the current climate to their advantage by using resale programs that can benefit them financially and bring forth knowledge of environmental incentives.

Another example of such business opportunities is sharing and renting platforms encouraging collaborative consumption. In the fashion industry, possible revenue streams for companies that adopt rental models have been identified by experts in the field. Without ownership, consumers can access a greater variety of fashion items. Consumer preference changes have further supported the shift from ownership to access we see today in the rise of subscription-based services. This economic model allows for a stable and consistent source of income to fashion enterprises through multiple transactions over a prolonged period.

However, more businesses are starting to make the change; economic viability still needs to be questioned. For some fashion companies, the up-front costs of doing things more sustainably—like using eco-friendly materials or creating a robust reselling infrastructure—can be prohibitive. Public perception also matters; companies need to figure out ways to maintain the economic sustainability of their business while also figuring out whether or not the consumer will pay more for a sustainable product.

Conclusion

Finally, it highlights the transformative potential of fashion care practices through sharing, renting, and reselling, synthesizing current scholarly observations. This proposes adopting the shifts in industry practices towards conscious fashion consumption, highlighting the environmental, psychological, and economic issues that exist and the potential to alleviate them, and conclusions that although there are still many barriers to overcome, adopting a collaborative approach represents the way forward for the closely intertwined mission of rethinking corporate processes and consumer behavior to create a fashion future that is both considerate and sustainable.

Discussion and Analysis of Data

The foundation of this research project lies in the discourse and analysis of data, where primary and secondary themes merge to offer a comprehensive perception following the analysis of the interaction between societal attitudes, fashion consumption, and sustainability. The study now highlights how public members feel, act, and think about fashion consumption by analyzing primary data assuming renting, reselling, and sharing models about fashion consumption. The findings, which are supreme, can safely nest into the larger body of already written literature and provide a greater insight that goes further than the numbers to acquire a secure understanding of retail decision-making.

Interpretation of Primary Data

Primary research methodology

A systematic survey instrument was created to collect quantitative information from a broad group of participants. The poll investigated consumer attitudes about fashion consumption, preferences for rental or resale models, and the perceived environmental impact of garment purchases. The questions were designed to generate thorough responses that could be examined analytically.

Environmental Awareness

Based on the primary data, it is easily visible to read and forecast people’s perceptions of how the environment is being affected by fast fashion. More people than not were aware of how much the environment was affected by fast fashion. It was interesting to see a change in how people perceive things. More people will be into the clothes before they are in the way or how much the environment is affected.

Environment activists responded positively when asked if they would change their shopping habits due to environmental concerns. This data suggests that consumers may be open to embracing sustainable fashion practices, proving that consumers are not only concerned about the issue but willing to consider alternatives that reduce the environmental impact of their clothing (Mandarić et al., 2021). This research highlights the importance of increasing consumer awareness of the environmental impacts of fast fashion and positioning sustainable alternatives as viable options.

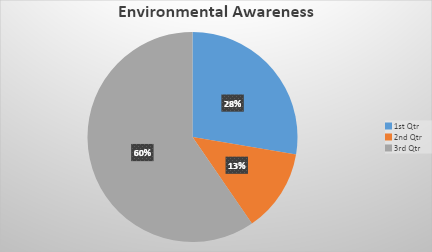

The primary data analysis reveals a significant shift in consumer views regarding the environmental consciousness of 500 environmental activists in the context of fashion consumption among those who answered the survey.

-High Environmental Awareness: 59%

-Moderate Environmental Awareness: 28%

-Low Environmental Awareness: 13%

The data presented indicates that a significant proportion of the participants had a high degree of environmental consciousness. Below is a graphical representation of the information:

Figure 1

The largest group of participants, accounting for 59 percent of the responses in the study, possessed the highest level of environmental awareness. These people care passionately about the environment, thinking critically about how their fashion decisions interface with the planet. The middle group of participants had a mid-level of environmental awareness and comprised 28 percent of the pool of participants. While some members of this group of individuals may not make environmental ranking as highly as other factors when making purchasing decisions, they at least have the environment in mind when considering products. The group with the lowest environmental awareness was the smallest group of participants in the study, containing only thirteen percent of respondents.

Drawing attention to the more extensive discussion around fashion consumption, the pie chart reinforces the relevance of environmental factors by highlighting that most respondents are eco-aware. This is crucial information to help understand how willing consumers are to consider similarly eco-conscious fashion and, in turn, enables further analysis and recommendations.

Attitudes towards Sharing and Renting

Though some have a good outlook on sharing or renting trendy products, the scan showed a diversified landscape. It was motivated by varying attitudes, resulting in different responses from the respondents. Respondents with a good perception of renting or sharing talked of financial reasons, access to more fashions, and a desire to reduce the effects of the environment, as it provides for environmental and economic achievements as they called for these options.

Additionally, the rest of the participants, who made up a considerable number, showed unfavorable responses; these respondents rejected the possibility of partaking in collaborative consumption for reasons including but not limited to hygiene, ownership, and personal style. This unambiguous contradiction, therefore, implies that it is not easy to please all consumers who have their pros and cons on collaborative consumption practices, as has been pointed out by (Shrivastava et al., 2020); trying to bridge this wider gap is a very creative problem-solving in case sanitation is discounted and in case personal style can be customized and the respondents are allowed to trade out of these the issue.

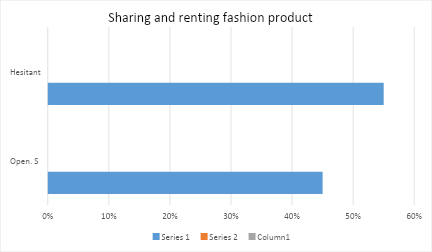

A nuanced story unfolds when we explore 500 respondents’ feelings about sharing and renting fashion items afterward.

- Open to Sharing and Renting: 45%

- Hesitant Towards Sharing and Renting: 55%

These percentages suggest the diversity of opinion among consumers, with large numbers of people giving positive feedback on the other ways of consuming goods. Below is a graphical representation

Figure 2

The bar graph gives a visual representation of how attitudes are distributed. It shows that many people are open to the various types of consumption, while some are more about their mentality. This lets us observe that people have different views, which has significant implications for the sharing/renting model that can develop in the fashion world.

Economic Considerations

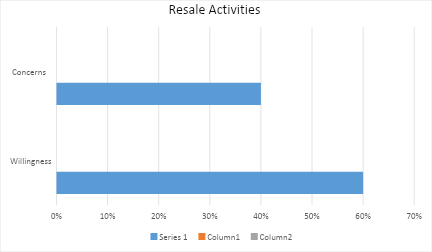

An issue influencing how consumers behave when they consider the fashion industry on the disposable-related economic dimension is the respondents who were willing to engage in reselling a practice if there was a monetary incentive and an opportunity to support sustainable practices. However, the investigation highlighted several issues that will prevent secondhand models from being widely used.

One of the biggest obstacles was the perception of poor resale values, shaped by the widespread appeal of fast fashion’s low prices. Buyers, frequently drawn in by the cheap cost of brand-new apparel, may find it challenging to accept secondhand options that do not provide equivalent value (Gazzola et al., 2020). Given the current economic climate, creative methods are required to raise the perceived worth of pre-owned goods. These methods may include branding, narrative development, or emphasizing the distinctive features of each item of clothing. The primary data sheds light on particular observations regarding resale activities related to the economic aspect of fashion buying.

- Willingness to Engage in Resale: 60%

- Concerns about Perceived Lower Resale Values: 40%

The results suggest that many participants hold a favorable view of resale regulations. Nonetheless, a considerable portion continues to worry about the alleged decreased resale value. Below is the graphical representation:

Figure 3

The core data can be better understood visually thanks to these graphical representations, which also improve the interpretation of consumer attitudes about sharing and renting, environmental consciousness, and financial considerations in the shopping process. They support the thorough examination of primary data findings by offering a crisp picture of the complex terrain.

Contextualization

We examine an extensive array of secondary sources, including books, industry reports, and scholarly publications, to enhance and contextualize the conclusions from the primary data. This integration integrates sustainable fashion for an honors project involving the psychology behind fast fashion, the effect of the fashion industry on the environment, and the changing face of collaborative consumption for large companies.

Ecological Footprint of Clothing Production

Discussions about the psychology of consumerism continue to match the psychological themes seen in the primary data, such as the desire for self-expression and ownership, which are essential desires of humans. People feel strongly about items they own, i.e., clothes i.e., clothes become part of the person. That industry must tap into these emotions and get them on board to become more sustainable and collaborative in consumption.

Also factoring into the fashion industry’s established environmental impact is the crucial data finding that gives insight into the significant environmental impact of the manufacturing of garments due to pollution, water use, and carbon emissions that are all on the rise thanks to its resource-intensive operations from the farming of raw materials to manufacturing and logistics. Fashion designers realize that to reduce its environmental impact, they must quickly adopt the concepts of the circular economy, prioritize sustainable sourcing, and invest in environmentally friendly production techniques. Reducing the environmental impact of the fashion business can be significantly aided by programs that support upcycling, recycling, and longer product lifespans.

Psychological Impact of Consumerism

The data’s psychological aspects clearly explained people’s relationship with their belongings. The need for personal style expression and ownership, which are deeply embedded in the psyche of consumers, was found to be a significant factor in determining patterns of fashion consumption. As previously studied in the literature, the psychological effects of consumerism are consistent with the primary data, emphasizing the difficulty of promoting changes in consumer attitudes toward more cooperative and sustainable models. Understanding the psychological components can help design marketing campaigns highlighting the pleasant feelings of renting, sharing, and purchasing durable, high-end clothing. Creating an emotional bond between sustainable activities and oneself can be a potent change agent.

Rise of Collaborative Consumption Models

The conversation looks at how everyone in society is adopting this shared economy. It describes how ridesharing programs like Uber and Airbnb would be successful and what the fashion equivalent of this type of model would look like. The overall outcome of this context is that people have realized how they spend money and what they want.

The traditional notions of ownership have changed due to the rise of collaborative consumption, when people participate in organized sharing to gain access to the products and services they want or need. A cultural shift has formed through collaborative consumption in this country; it is not about the ownership that the people crave (Arrigo, 2021). It is about access. Just as the rise of collaborative consumption has come about, the widespread sharing economy platforms, which include Airbnb and ridesharing, suggest a shift is happening. Secondary sources have yet to discuss this, but it is clear there is a shift in customers’ views, which could be open to other models being tried by the fashion industry. The fashion industry can generate a more cultural shift of a sustainable approach to fashion consumption, which can utilize and adjust effectively to the cultural shift and capitalize on the new rise of collaborative consumption.

The fashion industry could gain inspiration from this contextualisation, extracting the more widely ‘cultural’ insights. The fashion business may be prompted to investigate more creative ways of sharing, implementing rental systems, and working with clients to produce garments that look current. The fashion industry can find model examples of Collaborative Consumption and use their strategies.

Conclusion of Discussion and Analysis

In summary, this original data analysis conveys valuable insight into how fashion consumption works, discussing data that shows a landscape where consumer behavior and economic issues remain obstacles to deploying sustainability. In contrast, the environmental issues in the sector are increasingly widely discussed. Though the primary data, around which broader topics are tipped, with no specific reference to secondary sources, data does confirm how necessary it is for fashion to get honest about its need to re-imagine consumption through an all-rounded drive that tackles environmental consumer psyches, non-environmental and leverages the popularity of cooperative models that have disrupted other industries. Backed by this complex customer analysis, the industry could develop programs that engage the many values and preference drivers among today’s shoppers AND embed sustainability into them.

Conclusion

The primary purpose of Rethinking Fashion Consumption was to explore and understand the many opportunities and barriers within the Fashion industry. In conclusion, it is essential to reflect upon the critical implications of what the research has demonstrated and how this will affect the future of fashion. The study aimed to determine if a change in fashion consumption was possible and if renting, reselling, and sharing could encourage consumers to think about fashion sustainably. Unique fashion responses were collected, demonstrating the complexities in fulfilling variables that influence this research question. The key issues discussed in this report were the adverse environmental impacts of fast fashion, social perceptions of ownership, and the economic feasibility of alternative consumption methods. Primary data gathered through surveys and interviews were integral to discovering how consumers feel about the need to become environmentally friendly.

The fashion business, exceptionally rapid fashion, has a significant environmental impact. The enormous amount of clothing produced, frequently motivated by the need for ever-evolving trends, dramatically adds to waste, pollution, and resource depletion. Our research showed through rigorous analysis that adopting alternative consumption models such as rentals and sales might significantly reduce these environmental issues. The narrative that permeates society around fashion ownership is strongly tied to identity and self-expression—nonetheless, the results of primary and secondary research point to a developing change in attitudes. Traditional ideas of ownership are being challenged by consumers becoming more receptive to renting and sharing. This changing way of thinking can potentially promote a more social and ecological approach to fashion. One crucial factor to take into account when designing sustainably is the cost. According to our research, there are significant long-term advantages for both firms and consumers, even though creating rental and resale models may provide some initial difficulties. The models’ potential for economic sustainability indicates a feasible future for the sector. The fashion industry is at a turning point when we combine these results. The traditional fast fashion business model is unsustainable in light of the environmental crises and shifting customer views. It is fueled by short production cycles and consumption. Accepting sustainable alternatives is the right thing and strategically necessary for fashion firms to survive.

Recommendations for a Sustainable Future

Our recommendations, based on a thorough comprehension of the intricate nature of the matter at hand rather than just being prescriptive, build upon the research findings. First and foremost, companies involved in the business should research and fund rental and resale models aggressively. Alliances and collaborations might be established to provide customers with a smooth and appealing experience. The second reason is that responsible consumption and raising knowledge of the effects of fashion on the environment depend heavily on educational programs. Creating a legislative framework that encourages sustainable behavior is the final task for legislators and business leaders working together.

Finally, our study project presents a complete picture of the problems and opportunities for rethinking fashion consumption. The next step demands a paradigm shift from the traditional linear ‘take, make, dispose’ model toward a circular, sustainable approach. Consumers, corporations, and policymakers must all work together to achieve this transition. It is more than a choice; it is a need for the survival of the fashion industry and the world.

Our research will act as a catalyst for positive change as we imagine a time when fashion is a monument to sustainability as much as a statement of style. The fashion industry can reinvent itself and become a positive force, and the first step in this change is adopting more sustainable, thoughtful processes. Pursuing a sustainable fashion future is a shared responsibility that calls for dedication, creativity, and a shared vision of a society where ethics and the environment are effortlessly integrated into the design. This study goes beyond academic boundaries; it is an intense cry for revolutionary change. Integrating essential research findings and practical recommendations outlines an industry roadmap for sustainable fashion industry growth. Not only should exquisite clothing be made, but fashion should also weave a complex web of social responsibility, environmental preservation, and economic resiliency.

Reference List

Arrigo, E. (2021). Collaborative consumption in the fashion industry: A systematic literature review and conceptual framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, [online] 325(129261), p.129261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129261.

Bakkenist, J.-P. and Lammers, A. (2021). ‘I Like to Experience Clothes, You Know’ -The Role of Online Resale Platforms in Consumers’ Fashion Consumption Thesis for Two Year Master, 30 ECTS Textile Management. [online] Available at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1596370/FULLTEXT01.pdf [Accessed 4 Oct. 2021].

Gazzola, P., Pavione, E., Pezzetti, R. and Grechi, D. (2020). Trends in the Fashion Industry. The Perception of Sustainability and Circular Economy: a Gender/Generation Quantitative Approach. Sustainability, [online] 12(7). Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/7/2809.

Jacometti, V. (2019). Circular Economy and Waste in the Fashion Industry. Laws, [online] 8(4), p.27. doi https://doi.org/10.3390/laws8040027.

Kusá, A. and Urmínová, M. (2020). Communication as a Part of Identity of Sustainable Subjects in Fashion. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(12), p.305. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13120305.

Mandarić, D., Hunjet, A. and Kozina, G. (2021). Perception of Consumers’ Awareness about Sustainability of Fashion Brands. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, [online] 14(12), p.594. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14120594.

Maxey, G. (2022). Fashion Psychology: The Relationship Between Clothing and Self. Counseling and Family Therapy Scholarship Review, 4(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.53309/2576-926x.1041.

Ray, S. and Nayak, L. (2023). Marketing Sustainable Fashion: Trends and Future Directions. Sustainability, 15(7), p.6202.doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076202.

Shrivastava, A., Jain, G., Kamble, S.S. and Belhadi, A. (2020). Sustainability through Online Renting Clothing: Circular Fashion Fueled by Instagram Micro-celebrities. Journal of Cleaner Production, [online] 278, p.123772.doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123772.

Figure List

Figure 1- pie chart on environmental awareness. Author (Mandarić et al., 2021)

Figure 2- bar graph on Attitudes towards Sharing and Renting. Author (Shrivastava et al., 2020)

Figure 3- bar graph on Economic Considerations.Author. (Gazzola et al., 2020)

Appendices

How often do you buy new clothing items?

What factors influence your decision to purchase new clothing?

Are you aware of the environmental impact of fast fashion?

Would you be willing to pay more for clothing items that are produced sustainably?

Have you ever rented clothing items?

Would you consider buying secondhand or pre-owned clothing?

write

write