Introduction

The Indian healthcare sector, characterized by the coexistence of different forms of ownership and various medical system distribution, is confronted with a significant problem related to health workers’ emigration (Karan et al., 2021). The Indian healthcare system applies allopathic practices and indigenous systems like Ayurveda and homeopathy to try out people’s vast heterogeneous healthcare requirements. This is, however, marred by the skewed distribution and low density of health workers, as reported recently in a report from the World Health Organization (WHO) (Karan et al., 2021). According to the report, India will need 1.8 million doctors, nurses, and midwives with a target of finding at least some support for these professions before it can reach its minimum threshold by 2030, whereby every country should have about 44.5 health workers out of every population base formed from an aggregation figure made up that is measured over each set (10,000) (Karan et al., 2021).

Additionally, the shortage of trained nurses is among many problems, with the primary cause being a limited number of establishments that impart nursing training and the increasing trend of Indian nurses migrating to other countries. This means that India has become a significant force in the global nursing workforce, as every year, approximately 25,000 trained nurses leave for opportunities beyond its borders (Thompson and Walton-Roberts, 2018). India is high on the list of migrant nurses’ origin countries, especially seen in data provided by destination nations. For example, Thompson and Walton-Roberts (2018) state, “the National Council of State Boards of Nursing” in the US, a major destination for internationally trained nurses, had India, along with the Philippines, on top among countries sending away high amounts of nurse applicants to applying for US nursing registration exams.

Argument: This essay argues that the migration of health care providers to India calls for analyzing two major approaches—investing in human capital and ethical hiring. Through evaluating global cases and contextualizing Indian healthcare provision, this analysis testifies to their perceived efficacy.

Investment in Education and Training

A significant investment in education and training is one of the vital primary responses to mitigate negative implications stemming from health worker migration in India (George and Rhodes, 2017). This includes physicians and nurses, critical elements of the health care team. In nursing, qualifications required for government service highlight the value of education and experience. As noted by George and Rhodes (2017), in India, a nurse working in the government sector should have either a Bachelor of Science degree along with practice for half a year or a diploma, also known as general medical nursing, but more importantly accompanied by Social contribution towards solving national issues. This reinforces the need for standardized and accredited education that meets the demands of healthcare workers.

Moreover, India’s 2017 National Health Policy identified the need to reinforce the current medical education system and suggested developing mid-level healthcare providers to solve physician shortages (George and Rhodes, 2017). This is a well-calculated strategic opening to broaden the base of healthcare professionals beyond what has traditionally been defined, in line with global efforts to diversify health delivery (George and Rhodes, 2017). The increase in medical schools plays a central role in solving physician shortages. Rizwan et al. (2018) noted that medical education has been increasing around the globe, with over one-third of all health schools located in countries like India. China’s approach to reform initiatives, such as merging schools and increasing enrollment, has been fruitful since more medical school students are produced (Rizwan et al., 2018). Similarly, projections show that India will reach the recommended WHO ratio of one doctor per 1,000 people with an estimated 1,493,385 registered doctors by 2024 (Rizwan et al., 2018). This growth has the potential to increase physician accessibility in the country.

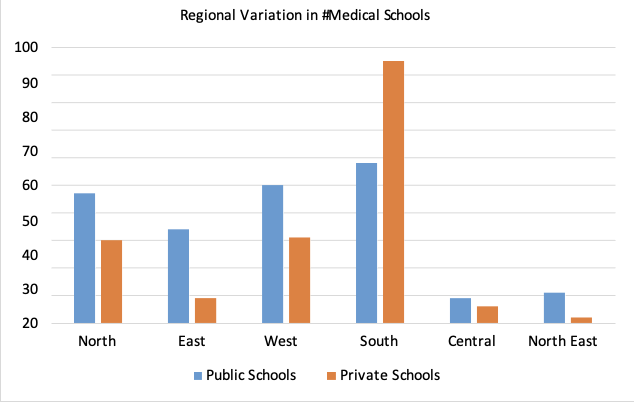

Fig 1: “Number of medical colleges across regions of India” (Ravi, Gupta, and Williams, 2017)

To some extent, the investment in education has shown promising results by minimizing health worker migration in India. New institutions, especially in less developed states and distant places, have proven higher retention of healthcare professionals in local areas (Karan et al., 2023). This geographical pattern coincides with effective patterns demonstrating the positive relationship between local training and eventual retention. Still, it is crucial to focus on the quality of educational institutions in such areas as remote ones so that their workforce will be skilled and competent (Karan et al., 2023). Indeed, the strategy’s success depends not only on institutional enlargement but also on parallel processes. Measures such as raising public health spending, attracting talent to the nursing workforce, and preparing healthcare settings to absorb the increasing supply are critical complementary steps.

Counter-argument: Challenges in Expanding Medical Education in India

Although the Indian government has succeeded in increasing the number of medical school graduates, there are serious problems associated with expanding medical education, as many private and even for-profit schools have been created (Rizwan et al., 2018). India leads the way in implementing private medical schools, which constitute a large proportion of the 356 new medical schools established recently, but this policy raises questions about quality education. Specifically, 194 of these 356 medical schools are private (Rizwan et al., 2018). These private schools are primarily driven by the need to make money through students’ enrollment, which may affect their focus on quality education.

According to Rizwan et al. (2018), medical education, mainly its privatization, introduces several problems, including scarcity of postgraduate opportunities, for instance, residency and fellowship programs. Funds for training programs are stretched beyond capacity by the government, intensifying the problems associated with setting up a strong healthcare workforce. Also, the profit-oriented paradigm can result in substandard educational standards, as Rizwan et al. (2018) revealed. Many private medical schools need recognition by governmental or accrediting bodies, so the lack of quality in education is questionable. In addition, the need for regular testing for admission to such programs further raises questions about whether these institutions generate highly qualified and capable healthcare professionals (Rizwan et al., 2018). Therefore, although the spread of medical training is a measure of addressing that shortage in health worker numbers, it must be realized just how crucial large-scale private and even for-profit institutions are to ensure those figures stay high on quality.

Additionally, ensuring equal access to education remains challenging (Thompson and Walton-Roberts, 2018). While the government partially subsidizes college education in India, seat availability might be limited for certain groups, such as lower-middle-class students, and reservations based on caste limit opportunities often (Walton-Roberts and Rajan, 2020). In such circumstances, many individuals aspiring to become healthcare professionals are forced to settle for nursing degrees from pricier private colleges, ultimately impinges on the availability and affordability of quality education (Thompson and Walton-Roberts, 2018).

Ethical Recruitment Policies

Furthermore, ethical recruitment policies are a significant way of counteracting health worker migration in India. Health policy and systems research are important in informing policies that must find a balance between addressing workforce shortages and still protecting workers’ interests. The migration of nurses and doctors, which is aimed at improving working conditions, originates from India’s constraints in specialist training (Walton-Roberts et al., 2017). This results in the management of the international recruitment process with ethical policies. Salary gradients, a major factor leading to the migration of health workers, can be controlled through broad-based national policies that include nonmonetary incentives as well (George and Rhodes 2017). These policies encourage adequate health workers to work in rural areas, hence reducing the dependence of healthcare funding on privatization. This includes strategic policy measures such as the intervention in unethical practices of private hiring agencies that facilitated nurse migration to Gulf countries (George and Rhodes 2017). Thompson and Walton-Roberts (2019) note the significance of policy interventions in identifying policies that protect healthcare professionals’ welfare, supported by actions undertaken by the Indian government on behalf of state recruiters and direct governments. As suggested by Chanda (2017), collaborative agreements with countries of origin add to the effectiveness of ethical recruitment policies. For example, though the Raffles Medical Group represents a commercial presence in Singapore, healthcare organizations’ alliances across borders are considered honest partnerships in global collaborations (Chanda, 2017). Hence, ethical recruitment policies, namely national strategies and international collaborations, have the capacity to address the harmful effects of health worker migration in India.

Counter-Argument: Gender Disparities and Vulnerabilities in Ethical Recruitment Policies

While such ‘protective’ policies were supposed to govern and safeguard migrants, predominantly female healthcare personnel, a contradictory viewpoint arises concerning gender-based inequality and the susceptibility of female immigrants. Thompson and Walton-Roberts (2019) indicate that the gendered discourses of these policies show unequal distribution of opportunities and rewards for women in international migration. Although the government has been trying to control illegal activities like high fees and false job offers during recruitment, women still face dangerous moments at this stage (Thompson and Walton-Roberts, 2019). ‘Protective’ policies, ostensibly implemented to safeguard the health of female workers in vulnerable jobs like those working for recruitment agencies, routinely wind up restricting these women from going mobile rather than preventing unscrupulous practices by their employers.

References

Chanda, R., 2017. Trade in health services and sustainable development (No. 668). ADBI Working Paper. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/163167/1/881178675.pdf

George, G. and Rhodes, B. (2017). Is there a financial incentive to immigrate? Examining the health worker salary gap between India and popular destination countries. Human Resources for Health, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0249-5.

Karan, A., Negandhi, H., Hussain, S., Zapata, T., Mairembam, D., De Graeve, H., Buchan, J. and Zodpey, S. (2021). Size, composition, and distribution of health workforce in India: why, and where to invest? Human Resources for Health, [online] 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00575-2.

Karan, A., Negandhi, H., Kabeer, M., Zapata, T., Mairembam, D., De Graeve, H., Buchan, J. and Zodpey, S. (2023). Achieving universal health coverage and sustainable development goals by 2030: investment estimates to increase production of health professionals in India. Human Resources for Health, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-023-00802-y.

Ravi, S., Gupta, D. and Williams, J., 2017. Restructuring the Medical Council of India. Available at SSRN 3041204. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/impact-series-paper-mci-sravi3.pdf

Rizwan, M., Rosson, N.J., Tackett, S. and Hassoun, H.T., 2018. Globalization of medical education: current trends and opportunities for medical students. Journal of Medical Education and Training, 2(1), pp.35-41.

Thompson, M. and Walton-Roberts, M. (2018). International nurse migration from India and the Philippines: the challenge of meeting the sustainable development goals in training, orderly migration, and healthcare worker retention. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(14), pp.2583–2599. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2018.1456748.

Thompson, M. and Walton-Roberts, M., 2019. International nurse migration from India and the Philippines: the challenge of meeting the sustainable development goals in training, orderly migration, and healthcare worker retention. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(14), pp.2583-2599. https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/250055/569E0C39-7583-45E9-9087-1674CFFB6DC4.pdf

Walton-Roberts, M. and Rajan, S.I., 2020. Global demand for medical professionals drives Indians abroad despite acute domestic healthcare worker shortages. https://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=gnmp

Walton-Roberts, M., Runnels, V., Rajan, S.I., Sood, A., Nair, S., Thomas, P., Packer, C., MacKenzie, A., Tomblin Murphy, G., Labonté, R. and Bourgeault, I.L. (2017). Causes, consequences, and policy responses to the migration of health workers: key findings from India. Human Resources for Health, [online] 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0199-y.

write

write