For some teachers, their beloved professional career morphs and takes an unexpected emotional turn. From excitement to exhaustion, thriving to survive, a sense of hollowness slowly replaces the spark of hope. These feelings are part of a phenomenon called compassion fatigue. Researcher Charles Figley studied helper burnout and introduced the term compassion fatigue by identifying the core causal factors (1995). Figley noted the cost of caring for others in emotional or physician pain. Further, Figley stated, “The most insidious aspect of compassion fatigue is that it attacks the core of what brought us into this work: our empathy and compassion for others (p. 53).” This paper explores the concept of compassion fatigue in teachers and a program designed to support teacher well-being.

Compassion Fatigue

Compassion fatigue is not synonymous with “burnout,” according to The American Institute of Stress (2019). Burnout is a cumulative process marked by emotional exhaustion and withdrawal, associated with increased workload and institutional stress, yet is not trauma-related (2019). Compassion fatigue arises from prolonged exposure to the distress and challenges of caring for others. Teachers are at a disadvantage as children under their tutelage and care may bring with them profound experiences of trauma. Teachers may internalize the students ‘ emotions without the skillset to handle traumatized children. According to Maslach et al. (1997), burnout results from a breakdown in coping ability. It has three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and feelings of a lack of personal accomplishment. Muzar and Lynch (1989) reported that teachers have higher scores of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization with a lower sense of personal accomplishment than workers in other human service fields. These factors may be why burnout is linked to teacher shortages. Richards (2012) listed the factors related to teacher stress levels. This included managing misbehaviour, supporting needy or unmotivated students, overwhelming workload, feeling disregarded in decisions affecting them and their students, and feeling the constant pressure to be accountable for student outcomes. The student roster remains on the teacher’s mind during non-instruction hours. Marking, reporting, responding to emails, and following up on anecdotal recordings take time and energy, exacting a toll on teachers. There is little time to enjoy life outside of school. Any combination of these stressors may overextend teachers, resulting in mental health crises leading to medical leaves or attrition.

How can teachers mitigate compassion fatigue?

What program supports teachers’ wellness, taking into account all contributing factors? One approach with emerging research evidence is Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education (CARE for Teachers) program. In 2007, supported by the Garrison Institute, Patricia Jennings, Christa Turskma, and Richard C Brown developed the CARE program. Of note, CARE was designed by teachers, increasing its reception by teachers. This paper will be an in-depth review of the CARE Teachers Program. Supported by research, it will demonstrate how participating in this program is a practical remedial approach for teachers with compassion fatigue. Jennings et al. (2017) outline a helpful and sustainable protocol for teacher wellness.

CARE A Mindfulness Program

Responding to the need to support teachers with compassion fatigue, Jennings and Greenberg (2009) designed a mindfulness practice for teachers through professional development, also known as the Prosocial Classroom. The whole intent of the program was to create a stable and balanced learning and teaching environment for teachers and students (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009). A Prosocial classroom is an environment that fosters positive behaviours and interactions while emphasizing a sense of belonging and citizenship. Teaching empathy and a spirit of cooperation through set skills taught and modelled by the teacher. Within the design of the Prosocial Classroom Mediational Model, teacher social and emotional competence (SEC) and well-being work together to support positive classroom interactions (Jennings et al., 2009). CARE is a readily available resource accessible through different channels. CARE Instructors offer retreats, online sessions, or face-to-face workshops CARE through mindfulness instruction.

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) defines SEC through five competencies: interpersonal skills, self-awareness, and self-management (Zins et al., 2004). CARE directs teachers to become aware of their interpersonal skills and learn to recognize and assess their emotions. Through this awareness, teachers can begin to see how connecting the mind to the physiological response and then applying mindfulness techniques will support positive class interactions. According to Jennings (2007), teachers who monitor personal emotions can accept their strengths and weaknesses with self-compassion. Teachers often demonstrate compassion for students yet fail to self-administer. For teachers with compassion fatigue, one of the miscued ruminations regarding self as incompetent, this is a necessary process to learn. The beginning of wellness. Teachers’ intrapersonal skill sets developed through Prosocial Classrooms create an emotionally safe environment that helps “students exposed to trauma adapt to the school environment (Jennings, 2018).” Using reflective self-management thinking, teachers can moderate reactivity even in provocative circumstances. Teachers who correctly assess student emotions and cognitions, recognizing behaviours that may be from trauma, can then reciprocate compassion and empathy while maintaining autonomy. CARE works with teachers to help students self-regulate rather than resort to punitive or coercive methods of discipline. This shift from arbitrary punitive consequences ensures students’ and teachers’ well-being.

Social Emotional Learning

CARE, through the Prosocial Classroom, leans on forward thinking. Teachers are taught to be proactive and encouraged to be more authoritative. By systematically observing levels of student participation, emotional regulation, and monitoring for changes, a teacher can use expression and verbal support to promote learning readiness, according to Jennings et al. (2009). The Prosocial classroom model invites teachers to partner with students for social-emotional learning (SEL). SEL is an integral part of the CARE curriculum. CARE, as described by Jennings et al. (2017)

Following best practices in adult learning, CARE for Teachers introduces material sequentially, utilizing a blend of didactic (pedagogical), experiential, and interactive learning processes. The program presents a structured set of mindful awareness practices, including breath awareness, mindful walking and stretching, listening compassion practices, and didactic and experiential practices to promote emotional awareness and regulation. (p.6)

CARE Project Logic Model

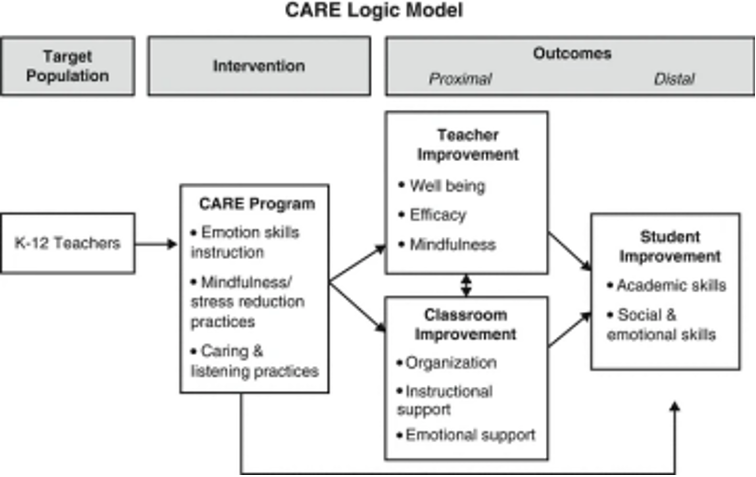

Figure 1 below depicts an outline of the progression from learning to implementation. Figure 1.

The model above champions teachers’ SEL, thereby increasing personal SEC. Improving self-efficacy and engaging in mindfulness (being present) improves the classroom climate (Jennings et al., 2009), from curriculum goals to socio-emotional development. When purposely implemented, this process strengthens and promotes emotional well-being for both teacher and student. Jennings et al. 2017 projected improvements in student achievement and social and emotional learning. SEL and SEC combined elements would synergize as intrapersonal and interpersonal skills would be refined and deployed effectively. Previous studies (Jennings et al., 2011, 2013) tested this hypothesis.

Research Supporting CARES

Jennings and Greenberg have continued to review and improve the CARES program. In 2012 (Jennings et al., 2017), a study was conducted in inner-city New York. According to Jenning et al. (2017, p. 5.), these 36 schools were chosen because of the high poverty circumstance and because previous research by CARE for Teachers provided strong results. Two cohorts were recruited from elementary schools. First contact with administrators with proposal and purpose of research, the invitation was welcomed. Jenning et al. required principals to release teachers for one day of CARE training during paid work time and to cover substitute costs (Jennings, 2017, p.5). According to Factor, impeding the request for teachers, too many programs, too few eligible teachers, or lack of interest. In order to participate, teachers had criteria to meet. This mandated teachers to be teaching in K-5 range of grades levels, general education (no specialists, e.g., art, music, physical education), no cotaught rooms, teaching one room all day, plus an average class size (Jennings et al., 2017, p.5). Teachers willing and able to fill the criteria attended the recruitment sessions where the innovative CARE program was explained (Jennings et al., 2017). One thousand eighty-four teachers were assessed, 491 did not meet the requirements for the study, and 68 were unable to participate, leaving 525 eligible participants (Jennings et al., 2017, p.5). A total of 224 teachers were willing to participate, while 301 declined. Control Group 1 C1 consisted of 53 teachers from 8 schools, while Control Group 2 C2 comprised 171 teachers from 28 other schools (Jennings, 2017, p.5). The attrition rate was a low 6%. Ninety-three per cent were females, and 7% were males (Jennings, 2017, p.5). 33% of the teachers identified as White, 31% as Hispanic and 26% as African American/ Black, 5% as Asian as well as 5% identified as mixed racial (2017, p.5). The age span of teachers ranged from 22-73 years with an Mdn = 40 (Jennings, 2017, p.5). The number of teaching years ranged from 0-32. Further data was collected. According to Jennings et al., 96% had a Master’s/Specialist degree and 1 Doctoral degree. Participants were 17-18% per grade, kindergarten through grade 5 (Jennings, 2017, p.5). 85% of participants taught general education, and the remainder from language teachers (e.g. ESL, ELL or bilingual (Jennings, 2017, p.5). Class sizes were smaller than the state average on the observation days, where the median was 25 students (Jennings, 2017, p.5). This was conducted as a randomized trial. As such, 118 teachers were assigned to receive CARE training, while 106 were waitlisted (Jennings, 2017, p.6). CARE for teachers proceeded through the fall and winter of 2012-2013 for C1 and C2 commenced in the spring (2017, p.6). All participants engaged in school-directed professional development days except one CARE training day for the intervention group at the time, C1 and C2 (Jennings, 2017, p.6). No statistical differences were found in professional development for both cohort and control groups (Jennings, 2017, p.6).

Intervention/ CARE for teachers

CARE is a prosocial classroom model designed to decrease teacher stress while addressing and supporting the SEC throughout one school year (Jennings, 2017, p.6). CARE training was delivered as 5 in-person, 6 hr days, according to (Jennings et al., 2017, p.6), while 2 of those days were consecutive and the rest 1 per month after that. The time between sessions presents the teacher’s implementation days, reflection and skill acquisition.

Description of each study and how it contributed to what we understand about the question (e.g., methods used, participants, findings)

Jennings et al. 2009, their study on the Impacts of the CARE for Teachers Program, established that The CARE for Teachers Study and the SMART Trial have substantially contributed to our comprehension of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) in teacher well-being and classroom dynamics. These studies, characterized by their comprehensive methodologies and rigorous analyses, provide valuable insights into the potential benefits of integrating mindfulness practices into the educational landscape.

The CARE for Teachers Study undertook a sizable endeavour involving 224 inner-city elementary school teachers within the United States. This randomized controlled trial aimed to evaluate the impacts of a mindfulness intervention on emotional exhaustion, teacher mindfulness, and occupational self-compassion. Furthermore, the study delved into the effects of the intervention on observed classroom interactions. The diverse cohort of participants consisted of educators from inner-city schools who sought professional development to enhance their well-being and classroom practices.

The study’s methods involved a five-day in-service training program throughout the school year—the curriculum aimed to improve emotional regulation and mindfulness, focusing on managing stress and enhancing interpersonal interactions. Pre- and post-intervention assessments encompassed self-report measures of teacher well-being and classroom observations to gauge the quality of interactions with students. The findings demonstrated significant improvements in emotional exhaustion, teacher mindfulness, and observed classroom interactions. Although the effect sizes were moderate, the results signified the potential of MBIs to influence teacher well-being and classroom dynamics positively.

In contrast, the SMART Trial focused on 113 elementary and secondary school teachers from Canada and the United States, adopting an eight-week intervention approach with 11 after-school sessions. The primary goal was to assess the impact of the mindfulness program on stress, burnout, anxiety, and depression among predominantly female and White participants.

The SMART Trial’s findings were significant, revealing a marked reduction in self-reported occupational stress, burnout, anxiety, and depression due to the intervention. This highlights the potential of mindfulness interventions to alleviate educators’ common mental health challenges.

Comparing these studies, demographic variations, program formats, and intervention durations shaped outcomes. The concentrated and intensive SMART Trial reported larger effect sizes, while the CARE for Teachers Study demonstrated moderate yet meaningful effects with a diverse sample and distributed intervention. Both studies, though distinct, underscore the potential benefits of MBIs in enhancing teacher well-being and fostering positive classroom interactions.

Thus, the CARE for Teachers Study and the SMART Trial offer comprehensive insights into mindfulness-based interventions’ role in teacher well-being and classroom dynamics. These contributions enrich the knowledge base, providing educators, policymakers, and researchers a foundation to develop strategies supporting teachers’ mental health and creating conducive classrooms. As the field of MBIs for educators evolves, these studies pave the way for further exploration and application, ultimately enhancing the educational experience for teachers and students.

Jennings’ (2016) study, part of the CARE for Teachers program, further enriches this understanding. Their various studies delve into the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on teachers’ well-being, stress reduction, and classroom dynamics. These insights deepen our grasp of how such interventions influence educators’ experiences and their ability to navigate the challenges inherent in teaching.

The first study centred on urban teachers in high-poverty schools. Employing pre-and post-test assessments, researchers explored the effects of CARE on teachers’ stress levels, well-being, and classroom management. The findings highlighted notable improvements in mindfulness, stress reduction, and emotional regulation among teachers. Their reported decreased stress related to time demands and enhanced emotional control underscored CARE’s potential to foster well-being and stress management within demanding environments.

The subsequent study shifted focus to student teachers and mentors within suburban and semi-rural school settings. By introducing a control group, the researchers examined CARE’s influence on autonomy supportiveness and mindfulness. In contrast to urban teachers, these participants displayed a different degree of engagement, satisfaction, or professional outcomes. This outcome divergence illuminated the significance of contextual factors and hierarchical dynamics when designing mindfulness interventions for distinct teaching contexts.

The third study embarked on a larger efficacy trial, encompassing teachers from high-poverty neighbourhoods across two cohorts. This investigation aimed to ascertain whether CARE’s impact on teachers’ social and emotional competencies (SEC) and well-being could manifest as enhancements in classroom atmosphere and student outcomes. Early findings from Cohort 1 revealed reduced anxiety, decreased task-related haste, and heightened efficacy among teachers exposed to the CARE program. The ongoing analysis of Cohort 2’s data promises to furnish further insights into the intricate interplay between CARE, teacher well-being, classroom ambience, and student achievements.

In addition to the studies, the fidelity of the CARE program underwent evaluation. This scrutiny gauged the coverage of core program components, participant engagement, and facilitator proficiency. The results affirmed that the CARE program was meticulously delivered, encompassing essential components, meeting participant objectives, and sustaining participant involvement. These outcomes validate the program’s effective execution and potential to yield positive participant outcomes.

Collectively, these studies enrich our comprehension of the potential advantages of mindfulness-based interventions for educators. The findings underscore the necessity of accommodating the varying demographic, environmental, and social elements influencing teachers’ experiences. Furthermore, the research underscores the importance of nurturing teacher well-being as a conduit to cultivate classroom ambience and augment student achievements. These findings underscore the ongoing requirement for research and adaptability to cater to the evolving needs of educators across different stages and circumstances of their professional journey.

Additionally, Kendrick, A. (2021) conducted studies on Emotional Labour and Educator Burnout. The first two-year study investigated emotional labour’s role in educator well-being within the education sector. Combining qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys, the research revealed that education workers routinely work emotionally to maintain a caring and secure classroom environment. Distinct mental and emotional distress levels were reported across various roles, with the highest levels observed among those working primarily with children and youth. This study’s outcome included the Compassion Continuum conceptual model, illustrating the experience of compassion in education. Тhe findings emphasized thе nееd for comprehensive interventions to address mental аnd emotional distress among education workers involved in crisis аnd trauma work.

The second study examined compassion fatigue and its connection to educator burnout, exploring the pandemic’s impact on compassion fatigue levels. Drawing from diverse education roles, the research showcased a significant segment of participants experiencing compassion fatigue while others reported compassion satisfaction. Burnout symptoms included physical and mental exhaustion, cognitive shifts, and reduced willingness to support colleagues and students. The study introduced the notion of depersonalization as an indicator of burnout, underscoring the importance of systemic problem-solving to counter burnout effectively. The research indicated the COVID-19 pandemic as a notable traumatic event that heightened compassion fatigue.

In the third study, HEARTcare planning emerged as a comprehensive intervention to manage mental and emotional distress among education workers. The framework promotes proactive well-being planning, encompassing individual health needs and broader systemic changes. The research stressed integrating HEARTcare planning into preprofessional education and offering professional development to existing education workers. Public communication was essential to underscore the link between educators’ well-being and student academic success. The findings emphasized the significance of addressing systemic troubles and fostering excellent work environments to safeguard training professionals’ nicely-being and keep a fantastic training system. This interconnected research drastically enhances our understanding of ways emotional labour, compassion fatigue, and burnout impact education workers. The research provides a comprehensive view of educators’ challenges by employing mixed-methods approaches and incorporating various participants. The collective findings underscore the necessity of holistic interventions and systemic changes to enhance education professionals’ mental and emotional health, benefiting students and the broader educational community.

In other studies, Koenig al. (2017) conducted a quantitative study on child welfare workers to investigate the relationship between burnout and compassion fatigue (CF) within this population. The study employed the Maslach Burnout Inventory – Human Services Survey and the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale to examine connections between burnout and CF. Participants from diverse child welfare backgrounds were involved. Findings established a positive correlation between burnout and CF, revealing their interconnectedness. Addressing both constructs emerged as crucial for child welfare professionals’ well-being.

Similarly, Koenig et al. (2017) investigated burnout and CF among educators. Quantitative methods utilized the Maslach Burnout Inventory – Educators Survey and the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale. The study focused on Canadian educators attending a voluntary workshop. Significant associations between emotional exhaustion, depersonalization burnout, and CF emerged. The sample consisted of 74 educators, with a gender distribution of 58 females, 2 males, and 2 unspecified participants. The study emphasized educators’ burnout and CF symptoms and their implications for student outcomes, highlighting the need for targeted interventions and support in education.

Summary of what is known and where we need to understand more

Exploring compassion fatigue (CF), burnout, and their impact on educators and professionals has yielded insights. Studies by Pryce et al. (2007) and Koenig et al. (2017) highlighted the positive correlation between burnout and CF, emphasizing comprehensive addressing. Research on educators’ emotional competence, like Jennings and Greenberg (2009), linked it to positive classroom outcomes. The CARE for Teachers program, explored by Jennings et al. (2017) and Jennings (2016), demonstrated the positive impact of mindfulness-based interventions on teachers’ well-being and classroom interactions. However, gaps in understanding still need to be addressed. Comprehensive interventions addressing underlying factors contributing to burnout and CF are needed. Exploring the connection between educator well-being and student outcomes and investigating effective strategies like mindfulness-based programs for mitigating burnout and CF warrant further research. External factors’ influence, such as labour negotiations and contextual differences in educational systems, must be considered in interpreting findings. Diverse global research can provide a nuanced understanding of burnout and CF’s implications. Research highlights the need for holistic approaches, more profound exploration, and contextual awareness to tackle burnout and CF and enhance educator well-being and classroom environments.

In conclusion, exploring burnout, compassion fatigue, and mindfulness-based interventions in the environment of educators and professionals has strengthened our understanding of the complex interplay between emotional well-being, classroom dynamics, and effective teaching. The studies emphasize the interconnected nature of burnout and compassion fatigue, emphasizing the need for comprehensive interventions that address both constructs. The eventuality of mindfulness-based interventions to enhance educators’ emotional competence and overall well-being while appreciatively impacting classroom relations highlights a promising avenue for promoting teacher effectiveness. Moving forward, these insights provide a foundation for further exploration and developing strategies that support educators’ mental health, creating conducive learning environments for educators and students.

References

Jennings, P. A., & Greenber, M. T. (2009). The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher Social and Emotional Competence in Relation to Student and Classroom Outcomes https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.3102/0034654308325693

Jennings, P. A., Brown, J. L., Frank, J. L., Doyle, S., Oh, Y., Davis, R., Rasheed, D., DeWeese, A., DeMauro, A. A., Cham, H., & Greenberg, M. T. (2017, February 13). Impacts of the CARE for Teachers Program on Teachers’ Social and Emotional Competence and Classroom Interactions. Journal of Educational Psychology. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/edu0000187

Jennings, P.A. (2016). CARE for Teachers: A Mindfulness-Based Approach to Promoting Teachers’ Social and Emotional Competence and Well-Being. 10.1007/978-1-4939-3506-2_9

Kendrick, A. (2021). Compassion Fatigue, Emotional Labour and Educator Burnout https://legacy.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/Publications/Research/COOR-101-30-7%20Compassion%20Fatigue-Executive%20Summary.pdf

Koenig, Adam; Rodger, Susan; Specht, Jacqueline (2017). Educator Burnout and Compassion Fatigue. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, (), 082957351668501–. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573516685017

write

write