Introduction to SERVQUAL in IT healthcare Systems

In the last three decades, new and emerging information technologies (IT) have changed the manner in which healthcare organizations perform their daily operations to meet patient needs. In addition to searching for approaches to effectively compete in an increasingly IT-dominated and exponentially growing healthcare field, organizations –both public and private-have sought enhanced IT management as a solution for most of their crucial organizational control aspects (Pekkaya et al., 2017). While IT integration into healthcare systems has significantly improved the way healthcare organizations offer services to patients, this unprecedented IT integration with healthcare systems has come at a cost: enormous expenditures and capital investments have been required to establish and keep the IT systems running. In Germany, for example, the Federal Ministry of Health (2021) says that the government is set to spend €200 million per year until 2024 as part of their effort to drive the digital transformation of the country’s healthcare system pursuant to the Digital Healthcare Act (DVG) of 2019. As a result of this hefty price tag of IT systems adoption for healthcare systems and as a pathway to improving the systems to realize value for governments/organizations and service quality for patients, IT service quality evaluation (SERVQUAL) of healthcare systems has become a core part of IT management. Using the Delhi healthcare system as a case study, this paper describes SERVQUAL before describing, evaluating, and reporting on the IT service quality of Delhi’s healthcare system.

In understanding the critical role of service quality evaluation (SERVQUAL) in reimagining and improving healthcare IT systems, it is pertinent to understand the concept of SERVQUAL. According to Pitt et al. (1997), SERVQUAL is an instrument meant for assessing customer perceptions of the quality of service they received from an institution or an organization. Consisting of 22-items used for assessment, the SERVQUAL model was developed by Berry, Zeithaml, and Parasuraman in 1988 and refined over time by numerous scholars; SERVQUAL encompasses five dimensions that assess quality. These dimensions include 1) Reliability: the system’s ability to deliver a promised service accurately and in a dependable manner; 2) Tangibles: the physical material, personnel, facilities, communication material, and equipment making it possible to render the service promised; 3) Assurance: the courtesy and knowledge of employees and the extent to which they relay confidence and trust in the IT system; 4) Responsiveness: the readiness and willingness to offer prompt services to customers and help them whenever they encounter problems with the system; 5) Empathy: the caring nature and attitude that guides personnel in the system to provide individualized care and attention to users (Ladhari, 2009). Using the often 23-item SERVQUAL instrument, consumer feelings and expectations regarding the quality of service are surveyed. The insights got from the survey can then be used to create benchmarks and entrench/improve best practices for service delivery through interpreting and comparing the scores of the groups assessed during SERVQUAL. Through SERVQUAL that measures firm-specific scores across multiple periods, it is also possible to establish and analyze trend-something that can help predict service quality delivery.

As customers/users interact with an IT system, there are five quality perspectives that can be used to characterize each step of the interaction in SERVQUAL. These perspectives can then be used to gauge quality based on the intentions of the service system user (Parasuraman et al., 1994). The first perspective is content, and this encompasses standard procedures that render the service as either quality or not. The second quality perspective is process quality, and this encompasses the quality of the service that the customer experiences as the service is being offered (Kim, 2010). Structure quality encompasses the materials and effort-including the personnel and tools- needed to provide the service and the way that the user perceives their quality in terms of adequacy, appropriateness, or even layout that effectively facilitates service provision. The fourth quality perspective under SERVQUAL is outcome, and this encompasses the quality of the service that the customer interprets after receiving the advertised service (Kim, 2010). The fifth and final quality perspective is impact, and this is all about the long-term quality effect that makes the IT service rendered memorable to make the user a loyal customer.

Prior to post-2010 IT systems discourse, SERVQUAL assessments primarily focused on evaluating the satisfaction of end-users with a standalone information systems application. What differentiates this from current SERVQUAL assessments is that contemporary SERVQUAL directly evaluates end-user perceptions of the experience they had with the IT system (Midor & Kučera, 2018). The present SERVQUAL is an improvement of the User Information Satisfaction (UIS) instrument, which identified three major perspectives of the IT system, including information about the product (healthcare in this case) and the functional attributes (information) about the same service. Using the 22-item instrument and improving on the User Information Satisfaction (UIS) instrument, SERVQUAL generates a reliable score that can then be interpreted to evaluate the functional performance of an IT system (Pitt et al., 1997).

IT SERVQUAL conceptual model

According to Parasuraman et al. (1994), SERVQUAL has different score measures, and to negate some of the issues arising from the difference-score measures, it is important to understand the three distinct cadres of IT services as inferred from the varying levels of customer behavioral feedback. Apart from guiding the adoption of the SERVQUAL assessment instrument, this can help in successfully managing a firm’s IT system. The first distinct level is the ideal level of IT service. This denotes the level of service quality that customers and suppliers would expect to receive to fulfill their requirements and based on their previous experiences and emerging needs (Kang & Bradley, 2002). The second level is the acceptable level of IT service, and this denotes the basic acceptable threshold of IT service that customers and suppliers expect, factoring in the technological, infrastructure, organizational, and personnel constraints and limitations. The third and final level is the perceived level of IT service, and this is the actual quality of service that customers and suppliers receive from the organization. In the case of IT SERVQUAL, healthcare systems customers (suppliers and users of the IT system) and even the healthcare system operators are often not aware of the technological, infrastructure, organizational, and personnel constraints and limitations, and this unawareness creates a service gap that can only be filled through proper and continuous SERVQUAL assessments (Wolniak & Skotnicka-Zasadzien, 2011).

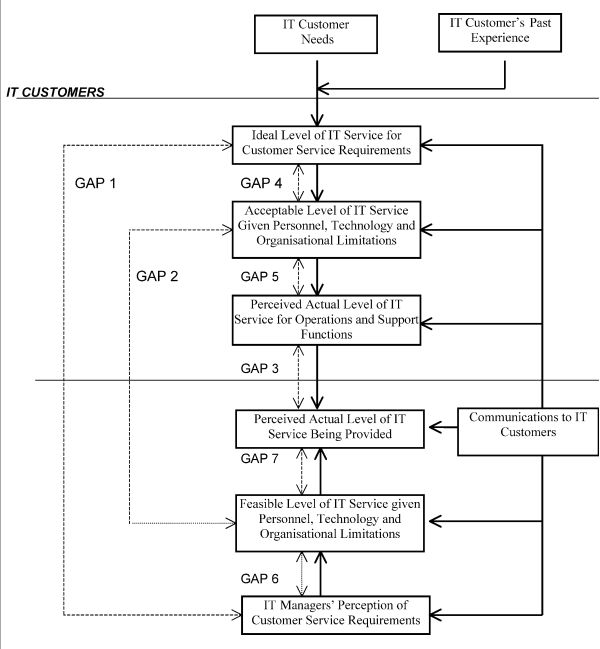

In SEVRQUAL, there is the idea of gaps that should be filled after proper assessment of a system. The four major gaps are 1) the knowledge gap, 2) the standards gap, 3) the delivery gap, and 4) the communications gap (Wolniak & Skotnicka-Zasadzien, 2011). However, researchers have identified other system-specific gaps. According to Kang & Bradley (2002), there are seven gaps between customers and suppliers of IT services that SERVQUAL evaluation (when done effectively) should fill. These include gaps between customers and suppliers of IT service, namely: the difference between customers’ and IT operators’ perception of the actual level of quality within the service system, the difference between customers’ and IT operators’ perception of the acceptable level of quality within the service system, and the difference between customers’ and IT operators’ perception of the ideal level of quality within the service system (Abu‐El Samen et al., 2013). For the customers of the IT system, the gaps are two. They include the difference between customer-acceptable level of IT service, and the actual level of quality of service perceived by the users, and the difference between what the users of the IT services would accept versus what they would want to get bearing in mind constraints related to infrastructure, personnel, and technology. The sixth and seventh gaps relate to the IT system managers’ perception of customer service requirements and the perceived actual level of the IT services being availed (See figure 1).

Fig. 1. The seven gaps model of SERVQUAL in IT

(Kang and Bradley, 2002)

Delhi’s Healthcare IT system

India, particularly the capital territory of Delhi, has been described as a region of great inequalities in healthcare service acquisition by citizens yet full of novel IT systems and quality healthcare ideas that place the region as one of the top healthcare tourism destinations in the country. Directly charged with providing healthcare services to residents of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCTD) is Delhi’s Department of Health and Family Welfare. In addition to curative, preventive, rehabilitative, and promotive health services, the department is charged with other healthcare services such as teaching, training, and research achieved through collaboration with other facilities within the Delhi area (Delhi Health & Family Welfare Department, 2020). Starting in 2019, the government of Delhi started implementing an $18.9 million cloud-based and fully integrated health information management system (HIMS) across its health facilities (The Hindu Times, 2021; Healthcare IT News, 2020). Among other features, and though yet to be fully implemented, the new IT system integrates all health facilities in India’s capital under one digital platform and can be used for all patient-related services spanning care planning, hospital booking for specialized care, e.g., surgery, eHealth cards for instant access to healthcare information, and general seamless information exchange between facilities within the HIMS (Delhi Health & Family Welfare Department, 2020). Thanks to the HIMS, patients seeking healthcare within the Delhi healthcare system are informed in real-time where they can get promptly get medicines and services like family mapping and emergency medical advice by simply logging into the CRM. This is all while allowing them to consult and book appointments with healthcare providers at home before they make the hospital visits, thus improving service delivery.

As expected, Delhi’s HIMS leverages India’s advancements in ICT to implement the citizen-centric IT system. According to Delhi’s Health & Family Welfare Department (2020), the six key objectives guiding the adoption of the HIMS IT healthcare system project are:

1) Enhance the quality of care in Delhi

2) Streamline processes at all Delhi public health facilities

3) Assist in public health governance and decision making through system-generated insights

4) Judiciously utilize available resources to enhance the efficiency of personnel in the healthcare system

5) Facilitate developments in healthcare through research initiatives and knowledge sharing

6) Ultimately improve patient experience in the Delhi public health system

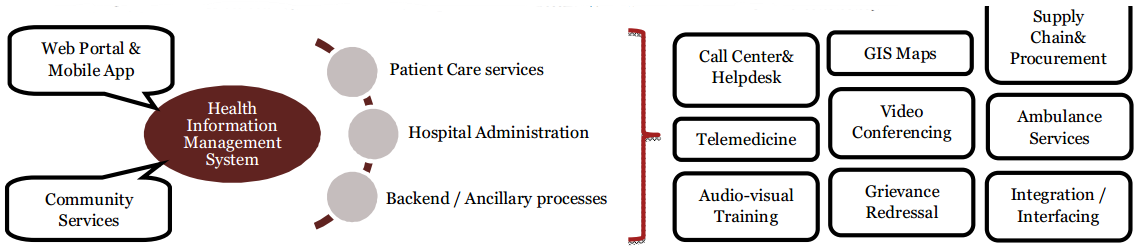

Delhi’s ICT-based HIMS presents itself as a critical driver in enhancing the healthcare system in Delhi, and to make the system responsive, reliable, and empathetic, the HIMS is spread across four key scopes. The first scope is patient care-related processes. This includes all the important steps in the patient’s journey through Delhi’s healthcare facilities; from registration, outpatient department consultations, laboratory investigations, inpatient department treatments, pharmacy, surgeries, blood bank requests, etc. (Delhi Health & Family Welfare Department, 2020). The second scope is hospital administration-related processes, and it includes all the activities that enable efficient management of healthcare facilities and the processes that support these hospitals, e.g., diet, laundry, store management, and maintenance support. The third scope is the ancillary /back-end processes, and it encompasses all the processes that facilitate effective management, governance, and planning of healthcare services across Delhi’s healthcare facilities. The processes covered include tender-based procurement, supply chain management for medicines and other hospital equipment, centralized procurement, and annual and interim budget estimations. Select users, e.g., media houses, researchers, and job seekers, may interact with such services. The fourth and final scope of Delhi’s HIMS encompasses supporting functionalities and additional features that facilitate miscellaneous processes that aid in the smooth running of the healthcare system’s services (Delhi Health & Family Welfare Department, 2020). Some of the functionalities under this scope include patient grievance redressal, GIS mapping for Delhi’s healthcare facilities and doctors locations-including real-time info updates, mobile-based applications, integration with ambulance trauma services, booking interface for community-based services, teleconsultations/telemedicine, and helpdesk/call center facility (See Figure 2 for more).

Figure 2. Overview of Delhi’s HIMS Healthcare IT system

(Delhi Health & Family Welfare Department, 2020)

Healthcare system in Delhi

To understand exactly how SERVQUAL will apply to Delhi’s healthcare IT system, it is important to understand how the general healthcare system in Delhi works. The government of Delhi provides healthcare services through a variety of health facilities ranging from multi-super specialty hospitals at the top to Aam Aadmi Mohalia clinics dealing with primary care at the very bottom (Express Healthcare, 2019). In between, we have society hospitals, dispensaries and seed PUHC’s, and polyclinics. These facilities avail preventive care and counseling services in addition to the usual tertiary, secondary, quaternary, and primary level care as sought by Delhi citizens. The health information management system (HIMS) seeks to achieve a unified, efficient, quality, and yet still tiered healthcare service delivery model across the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCTD). Except at select society hospitals where patients are charged nominally, all medicines and services at these NCTD hospitals are offered free of charge (Delhi Health & Family Welfare Department, 2020). Some of the facilities are regional centers meant to avail specific medical services (e.g., the GTB hospital is a regional blood transfusion center even though it falls under NCTD’s jurisdiction), and with an IT system in place, it would be expected that some of the service requests would come from outside Delhi.

The NCTD region has approximately 180 dispensaries spread across its 11 districts. The chief district medical officers are responsible for monitoring and assessing the quality of services in these facilities (Express Healthcare, 2019). To achieve this, they have mainly relied on hospital-specific statistics and word-of-mouth feedback from patients as facilitated by the door-to-door Aam Aadmi Mohalla Clinics (box-type movable structures) visits. For functionality purposes, AAMCS (Aam Aadmi Mohalla clinics) are linked to regional dispensaries, meaning that most feedback on health services quality is processed at the dispensaries (Rajagopalan & Choutagunta, 2020). Delhi, like the rest of India, mainly comprises a young-adult population (median of 29 years) that is technology-savvy. The implication of this is that it has been easy to easily extend medical care services to mobile health schemes residing in informal settlements (the JJ clusters) and via the school health system for school-going residents. These areas are pertinent to SERVQUAL evaluation.

Users of NCTD’s HIMS IT healthcare service system also have to rate SERVQUAL based on the auxiliary services provided by the 265-strong ambulance fleet. As mentioned before, emergency care communication within Delhi’s health information management system (HIMS) relies on the quality processes that happen when patients request ambulance services as facilitated by the regions 102 dedicated call centres, delivery and post-delivery transport general medical emergencies support. By carrying out SERVQUAL of Delhi’s citizen-centric HIMS, the strengths and weaknesses of the system can be identified to help improve the efficiency and productivity of the state-run hospital system/institutions, thus enhancing the overall healthcare system in Delhi. Apart from the citizens of Delhi who can benefit from this, SERVQUAL can provide valuable inputs to develop a solution framework benefitting healthcare resources like technicians, doctors, and nurses who are critical to the system’s functioning.

References

Abu‐El Samen, A. A., Akroush, M. N., & Abu‐Lail, B. N. (2013). Mobile SERVQUAL. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 30(4), 403-425. https://doi.org/10.1108/02656711311308394

Delhi Health & Family Welfare Department. (2020). Delhi HIMS Project (110002). Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi. http://health.delhigovt.nic.in/wps/wcm/connect/9cc748004b6f3a1a8a92cb788745c51a/HMIS.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&lmod=-382194844

Express Healthcare. (2019, June 6). Delhi’s government’s three-tier healthcare system will enhance public health. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.expresshealthcare.in/health-policies/delhi-governments-three-tier-healthcare-system-will-enhance-public-health/393194/

Federal Ministry of Health. (2021). Driving the digital transformation of Germany’s healthcare system for the good of patients. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/en/digital-healthcare-act.html

Healthcare IT News. (2020, August 30). Delhi announces $19M project to set up cloud-based hospital information management system. https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/asia/delhi-announces-19m-project-set-cloud-based-hospital-information-management-system

The Hindu Times. (2021, August 13). HIMS will transform healthcare system: Delhi CM. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/hims-will-transform-healthcare-system-delhi-cm/article35888040.ece

Kang, H., & Bradley, G. (2002). Measuring the performance of IT services: An assessment of SERVQUAL. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 3(3), 151-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1467-0895(02)00031-3

Kim, K. (2010). Understanding the consistent use of internet health information. Online Information Review, 34(6), 875-891. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684521011099388

Ladhari, R. (2009). A review of twenty years of SERVQUAL research. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 1(2), 172-198. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566690910971445

Midor, K., & Kučera, M. (2018). Improving the service with the Servqual method. Management Systems in Production Engineering, 26(1), 60-65. https://doi.org/10.2478/mspe-2018-0010

Parasuraman, A., Berry, L. L., & Zeithaml, V. A. (1994). Alternative scales for measuring service quality: A comparative assessment based on psychometric and diagnostic criteria. Journal of Retailing, 70(3), 201-230. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4359(94)90033-7

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality.

Pekkaya, M., Pulat İmamoğlu, Ö., & Koca, H. (2017). Evaluation of healthcare service quality via Servqual scale: An application on a hospital. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 12(4), 340-347. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2017.1389474

Pitt, L. F., Watson, R. T., & Kavan, C. B. (1997). Measuring information systems service quality: Concerns for a complete canvas. MIS Quarterly, 21(2), 209. https://doi.org/10.2307/249420

Rajagopalan, S., & Choutagunta, A. (2020). Assessing healthcare capacity in India. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3570651

Wolniak, R., & Skotnicka-Zasadzien, B. (2011). The concept study of Servqual method’s gap. Quality & Quantity, 46(4), 1239-1247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9434-0

write

write