This research’s findings indicated that the respondents supported the notion that limited oversight and non-regulation of humanitarian aid contributed to the corruption experienced in the humanitarian activities context. Limited oversight and non-regulation are internal factors inherent to the humanitarian organizations that increase the chances of encountering corrupt experiences when delivering humanitarian aid in Ukraine. Limited oversight and non-regulation are practices that contribute to overspending, especially in instances where high-value relief is involved. The findings presented in this research echoed the findings of Khan (2022), which indicated that massive aid with limited oversight could result in undesired outcomes such as increased corruption which is contrary to the objective of humanitarian aid. The case of Ukraine since its invasion, Ukraine has been characterized by high-profile donations in both cash and other in-kind donations from organizations and countries across the world (Antezza et al., 2022). The obscurity of humanitarian aid highlights the limited visibility in the provision of humanitarian aid, increasing the consequences of corruption on the quality and effectiveness of humanitarian aid provided to Ukraine.

When discussing the concept of limited oversight and regulation of humanitarian aid in response to the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation, it is important to note how the urgency of the situation affected the response of the aid agencies. According to Henson et al. (2010), humanitarian activities are characterized by a rapid response to ensure that the donations reach the affected people as fast as possible. In such scenarios, humanitarian organizations have limited time to provide oversight and regulate the expenditure directed at the purchase of goods and delivery of in-kind donations to the affected people (Labonte & Charles, 2016). The massive and rapid responses to the disasters, though, make some of these codes of conduct irrelevant where rapid procurement and responses are required for the aid to reach those affected within the shortest time possible. In this case, the need for oversight and regulation is often overridden by the desire of humanitarian organizations to provide aid to the affected people within the shortest time possible.

Other Factors Predisposing Humanitarian Organizations to Corruption in Ukraine

The findings identified another factor that increases corruption incidences in the provision of Humanitarian aid in Ukraine, which was the number of players and partners involved in the delivery of humanitarian aid. About 71% of the respondents recognized the influence of the number of players on exposing humanitarian activities to corruption. The outcome presented above echoed the findings of the previous studies, such as Ewins et al. (2006), who indicated that The number of players in the delivery of humanitarian assistance was identified by the previous researchers as one of the factors increasing the incidences of corruption in humanitarian activities. The higher the number of actors in the value and supply chains of humanitarian organizations, the higher the incidences of corruption. Martin et al. (2023) summarized this observation by stating that a “not-so-transparent system of delivery and distribution of humanitarian aid with a large number of actors is an ideal environment for corruption and corruption-related activities”. These findings indicate that the concerns of the respondents on the potential impacts of the number of players in increasing the incidences of the manifestation of corruption in the humanitarian aid provided to Ukraine were therefore supported.

Working with partners and local organizations is a key component in the operation of humanitarian organizations considering the high rotation of employees in different locations. The risk map developed by Ewins et al. (2006) acknowledged this source of the potential risk to humanitarian activities. The agreements with the local organizations and partners in the supply chain of the humanitarian organizations represent one of the high-risk areas when the problems with corruption are considered. The opportunity for corruption increases as the number of actors in the delivery of humanitarian aid increases. The risk is highest when the donors and their local partners have differences in the conception and handling of corruption in humanitarian aid (Maxwell et al., 2008). Humanitarian organizations often work with local partners to improve the delivery of humanitarian aid besides gaining access to information which makes their practices a success. These partners, therefore, are an inseparable part of the humanitarian organizations but ensuring more transparency and accountability is important in reducing corruption as the humanitarian organizations operating in Ukraine ply an environment characterized by deprivation and political instability.

Conclusion, Research Implications, Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Conclusion

This dissertation aimed to provide an empirical analysis of the effects of corruption on humanitarian activities in Ukraine. In support of the main aim, the secondary objectives of the research entailed exploring how the anti-corruption policies developed by the humanitarian organizations influence corruption outcomes and the impacts of limited oversight and non-regulation in the permeation of corruption in humanitarian activities. The findings acknowledged that corruption was a key concern in the delivery of humanitarian aid in Ukraine. Despite the concerns, the respondents did not indicate that corruption impeded the aid provided to Ukraine from reaching the intended beneficiaries even when they encountered the diversion of the aid to unintended targets when working in Ukraine. The respondents were aware of the policies, codes of conduct and other guidelines put in place by the respective humanitarian organizations to provide a basis for decision-making when presented with moral dilemmas in their work. The findings, though, indicated that the anti-corruption policies adopted by the humanitarian organizations bore little fruit in combatting corruption as the country factors and the nature of the humanitarian organization often conflicted with them. For example, the analysis findings indicated that the pre-war corruption, political instability, large-scale response and rapid response to assist the war victims in Ukraine reduced the effectiveness and efficiency of the humanitarian aid as the sole objective was to provide aid within the shortest time possible in an unstable political environment. The respondents indicated that government interventions had a higher chance of combating corruption in humanitarian aid compared to the internal policies put in place by the organization. Based on the summary provided above, it was concluded that corruption affected humanitarian activities in Ukraine, but the respondents remained divided on whether these corruption incidents hindered the aid from reaching the intended beneficiaries.

Research Implications

The outcomes of this research can be applied to various instances in assessing, understanding and addressing corruption in humanitarian aid. The implications of this research include the following:

First, the research findings acknowledged that corruption affected humanitarian aid in Ukraine. These outcomes indicate the need for strengthening the frameworks for the evaluation and monitoring of humanitarian aid. The frameworks developed should be though externally oriented in that they involve government interventions rather than the codes of conduct and regulations by the humanitarian organizations to instil ethical behaviour among the humanitarian practitioners. The interventions adopted by the humanitarian organizations are, therefore, powerless to address the issues of corruption in Ukraine, indicating that improving the environment has a better chance of reducing corruption which could potentially affect the delivery of aid to the affected people. The humanitarian practitioners’ behaviour is often focused on providing relief services and aid within the shortest time possible, indicating that they consider corruption as a necessary evil in delivering aid. In this case, the humanitarian organizations forego effectiveness and efficiency for a rapid response which further reduces the level at which the internal tools and procedures could be adopted to combat corruption when delivering humanitarian aid.

Second, the findings confirmed that the higher the number of actors in humanitarian aid provision, the higher the potential for corruption. Considering that the humanitarian organizations cannot do away with these partners as they are involved with ensuring the aid reaches the final destination. The humanitarian organizations, in this case, could adopt strategies such as contracting to provide more accountability and transfer the burden to another party to reduce the number of actors involved in humanitarian response. In another instance, humanitarian organizations should consider aligning their conceptions of corruption with those of their partners to cast a wider net to reduce corruption within their supply chains.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

First, this research originated from the quantitative methodology adopted. Although the study adopted a sample larger than that calculated by G-power to yield the desired outcomes, there is a chance that the findings could not be generalized to all humanitarian practitioners. In order to overcome this limitation, future studies should consider using a larger sample to improve the generalization and external validity of the research.

Second, this research provides an analysis of the influence of corruption on humanitarian aid. The quantitative inferences developed do not provide deeper meanings which is a limitation. Additionally, limited oversight was considered to increase corruption in humanitarian aid. The outcomes of this research did not explore how humanitarian aid contributed to the incidences of corruption in Ukraine. Future studies in this field should consider undertaking qualitative research to provide deeper meanings to the experiences of humanitarian workers with corruption while working in Ukraine. The studies should also explore the influence of humanitarian aid on corruption levels in Ukraine as part of providing a more nuanced exploration of the research subject.

References

Abrahamsson, H. and Ekengren, AM, 2010. Weakened willingness to help. The SOM Institute.

Acht, M., Mahmoud, T.O. and Thiele, R., 2015. Corrupt governments do not receive more state-to-state aid: Governance and the delivery of foreign aid through non-state actors. Journal of Development Economics, 114, pp.20-33.

Aliyu, A.A., Singhry, I.M., Adamu, H.A.R.U.N.A. and AbuBakar, M.A.M., 2015, December. Ontology, epistemology and axiology in quantitative and qualitative research: Elucidation of the philosophical research misconception. In Proceedings of the Academic Conference: Mediterranean Publications & Research International on New Direction and Uncommon (Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 1054-1068).

Antezza, A. et al. (2022). Ukraine supports Tracker Data Set, Ukraine Support Tracker data set | Kiel Institute. Ukraine Support Tracker data set | Kiel Institute. Available at: https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/data-sets/ukraine-support-tracker-data-17410/ (Accessed: February 3, 2023).

Asongu, S.A. and Jellal, M. (2013). “On the channels of foreign aid to corruption,” SSRN Electronic Journal [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2493353.

Azungah, T. (2018). Qualitative research: deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative research journal, 18(4), pp.383–400.

Bauhr, M., Charron, N. and Nasiritousi, N., (2013). Does corruption cause aid fatigue? Public opinion and the aid-corruption paradox. International Studies Quarterly, 57(3), pp.568–579.

Carr, I.M. and Breau, S.C., (2009). Humanitarian Aid and Corruption. Available at SSRN 1481662.

Clark, T., Foster, L., Bryman, A. and Sloan, L. (2021). Bryman’s social research methods. Oxford University Press.

Cooksey, B., (2002, December). Can aid agencies help combat corruption? In Forum on Crime and Society (Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 45–56). United Nations Publications.

Core Humanitarian Standard (2023). Core Humanitarian Standard. Core Humanitarian Standard. Available at: https://corehumanitarianstandard.org/ (Accessed: February 3, 2023).

Düvell, F. and Lapshyna, I., 2015. The Euromaidan protests, corruption, and war in Ukraine: Migration trends and ambitions. Migration Information Source, 15.

Ebrahimi, M., Eberhart, A., Bianchi, F. and Hitzler, P., 2021. Towards bridging the neuro-symbolic gap: deep deductive reasoners. Applied Intelligence, 51, pp.6326-6348.

Edelheim, J.R., 2014. Ontological, epistemological and axiological issues. In The Routledge handbook of tourism and hospitality education (pp. 30-42). Routledge.

Ewins, P., Harvey, P., Savage, K. and Jacobs, A., (2006). Mapping the risks of corruption in humanitarian action. Overseas Development Institute.

Glushko, I., & Kolchynska, K. (2023, February 20). The main amendments to criminal law and procedure during martial law: are November-December 2022 and January 2023. Lexology. Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=ba7895ee-29da-44de-9e67-123eb9fb4c79#:~:text=On%20November%2006%2C%202022%2C%20the,sentence%20imposed%20by%20the%20court.

HARVEY, PAUL (2015) Evidence on corruption and humanitarian aid – world, Evidence on corruption and humanitarian aid. ReliefWeb. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/evidence-corruption-and-humanitarian-aid (Accessed: February 3, 2023).

Heckelman, J.C., 2010. Aid and democratization in the transition economies. Kyklos, 63(4), pp.558-579.

Heiervang, E. and Goodman, R., (2011). Advantages and limitations of web-based surveys: evidence from a child mental health survey. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 46, pp.69-76.

Henson, S., Lindstrom, J., Haddad, L. and Mulmi, R., 2010. Public perceptions of international development and support for aid in the UK: Results of a qualitative enquiry. IDS Working Papers, 2010(353), pp.01-67.

Henson, S., Lindstrom, J., Haddad, L. and Mulmi, R., 2010. Public perceptions of international development and support for aid in the UK: Results of a qualitative enquiry. IDS Working Papers, 2010(353), pp.01-67.

Hilhorst, D. and Jansen, B.J., 2012. Constructing rights and wrongs in humanitarian action: contributions from the sociology of praxis. Sociology, 46(5), pp.891-905.

Holmberg, S., Rothstein, B. and Nasiritousi, N., 2009. Quality of government: What you get. Annual review of political science, 12, pp.135-161.

Humanitarian Aid Website. (2023). Humanitarian aid website. Interactive Map of the Humanitarian Assistance Provided to Ukraine to Date. Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://help.gov.ua/en/

Jakobi, A.P., (2013). The changing global norm of anti-corruption: from bad business to bad government. Zeitschrift für vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 1(7), pp.243-264.

Kabra, G., Ramesh, A., Akhtar, P. and Dash, M.K., (2017). Understanding behavioural intention to use information technology: Insights from humanitarian practitioners. Telematics and Informatics, 34(7), 1250–1261.

Khan, S. (2022). The pitfalls of Unsupervised Aid to Ukraine, Inkstick. Inkstick Media. Available at: https://inkstickmedia.com/the-pitfalls-of-unsupervised-aid-to-ukraine/ (Accessed: February 3, 2023).

Klomek, A.B., Sourander, A. and Gould, M., (2010). The association of suicide and bullying in childhood to young adulthood: A review of cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(5), pp.282–288.

Krasniqi, A. and Demukaj, V., (2021). Does aid fuel corruption? New evidence from a cross-country analysis. Development Studies Research, 8(1), pp.122-134. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21665095.2021.1919538

Labonte, M. and Charles, I.A., 2016. 8 The evolution of rights-based humanitarianism in Sierra Leone. HPG, p.89.

Li, L. and McMurray, A. (2022). “Corporate fraud comparison across industries,” Corporate Fraud Across the Globe, pp. 135–167. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-3667-8_6.

Macur, M., (2013). Quality in health care: Possibilities and limitations of quantitative research instruments among health care users. Quality & quantity, 47(3), pp.1703-1716.

Martin, P., Wu, O.Q. and Yakymova, L. (2023). “Anti-corruption and humanitarian aid management in Ukraine,” SSRN Electronic Journal [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4337527.

Martin, P., Wu, O.Q. and Yakymova, L., 2023. Anti-Corruption and Humanitarian Aid Management in Ukraine. Available at SSRN 4337527.

Maxwell, D. et al. (2011). “Preventing corruption in humanitarian assistance: Perceptions, gaps and challenges,” Disasters, 36(1), pp. 140–160. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2011.01245.x.

Maxwell, D., Bailey, S., Harvey, P., Walker, P., Sharbatke‐Church, C. and Savage, K., (2012). Preventing corruption in humanitarian assistance: perceptions, gaps and challenges. Disasters, 36(1), pp.140–160.

Maxwell, D., Walker, P., Church, C., Harvey, P., Savage, K., Bailey, S., Hees, R. and Ahlendorf, M.L., (2008). Preventing corruption in humanitarian assistance. Feinstein International Center Research Report.

Parsons, V.L., (2014). Stratified sampling. Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, pp.1–11.

Queirós, A., Faria, D. and Almeida, F., (2017). Strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods. European journal of education studies.

Rose, J. (2018). The meaning of corruption: Testing the coherence and adequacy of corruption definitions. Public Integrity, 20(3), pp.220–233.

Sandvik, K.B. and Lemaitre, J., 2013. Internally displaced women as knowledge producers and users in humanitarian action: the view from Colombia. Disasters, 37, pp.S36-S50.

Saunders, M.N.K., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students. Eighth edition. Harlow, United Kingdom: Pearson Education Limited.

Scott, J.M. and Steele, C.A., (2011). Sponsoring democracy: The United States and democracy aid to the developing world, 1988–2001. International Studies Quarterly, 55(1), pp.47–69.

Sommer, U., Bloom, P.B.N. and Arikan, G., 2013. Does faith limit immorality? The politics of religion and corruption. Democratization, 20(2), pp.287-309.

Svensson, J., (2000). Foreign aid and rent-seeking. Journal of international economics, 51(2), pp.437-461. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022199699000148

The Kyiv Independent news desk. (2022, June 23). SBU suspects local officials in Chernivtsi of humanitarian aid fraud. The Kyiv Independent. Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://kyivindependent.com/news-feed/sbu-suspects-local-official-in-chernivtsi-of-humanitarian-aid-fraud

Transparency International (2014). Transparency.org. Transparency.org. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/what-is-corruption (Accessed: February 3, 2023).

Transparency International. (2022). 2021 corruption perceptions index – explore the results. Transparency.org. Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021/

Transparency International. (n.d.). What is corruption? Transparency.org. Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://www.transparency.org/en/what-is-corruption#:~:text=We%20define%20corruption%20as%20the,division%20and%20the%20environmental%20crisis.

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2022). UN allocates USD 20M from CERF to the humanitarian response in Ukraine. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. URL: https://www.unocha.org/story/.

V-dem. (2022). Country graph – V-dem. Global Standards Local Knowledge. Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://v-dem.net/data_analysis/CountryGraph/

Wang, L., Zhang, M., Zou, F., Wu, X. and Wang, Y., 2020. Deductive‐reasoning brain networks: A coordinate‐based meta‐analysis of the neural signatures in deductive reasoning. Brain and Behavior, 10(12), p.e01853.

West, B. and O’Reilly, R., (2016). National humanitarianism and the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Journal of Sociology, 52(2), pp.340–354.

Appendix 1: Survey Questionnaire

Survey Questionnaire

Questionnaire

I agree to take part in the study research. I understand what is required of me and the nature of the research, and therefore, when I choose to participate in the study, my participation is voluntary. I understand that I am at liberty to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences or penalties.

Consent: Yes/No

Demographic Information

1. Please select your age group

| Age group | Select here |

| 18-24 | |

| 25-34 | |

| 35-44 | |

| 45-54 | |

| Above 55 |

2. Gender

| Gender | Select |

| Female | |

| Male |

3. Work experience in the humanitarian sector

Please select your work grade

| Duration of experience | |

| Below 1 year | |

| 1-3 years | |

| 4-6 years | |

| 7-9 years | |

| Above 10 years |

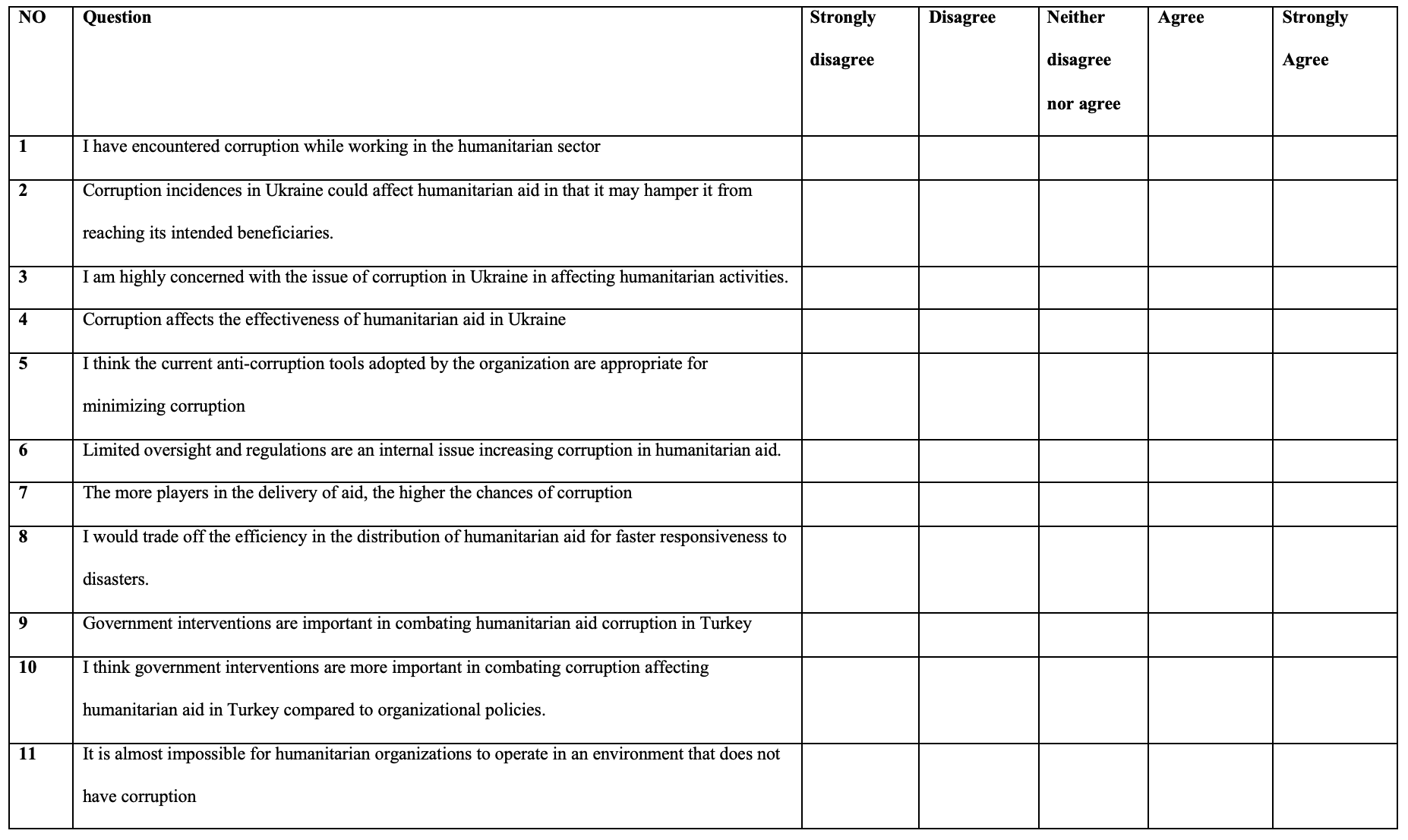

PERCEPTIONS ON HUMANITARIAN AID

Please answer the following questions about your perceptions of humanitarian aid as experienced in your work in Turkey

6. What are the most common forms of corruption that you are more likely to face when working in Ukraine as a humanitarian aid worker? (Please select only one choice from those provided)

| Bribes | |

| Nepotism | |

| Coercion of practitioners | |

| Financial fraudulent practices besides bribes | |

| Abuse of beneficiaries | |

| Diversion of some assistance to non-targeted areas |

write

write