Introduction

Systems thinking could help fix health problems caused by differences in income and social protection, according to this research paper. Traditional approaches have not been successful in reducing socioeconomic factors like income to fix the growing gaps in healthcare access and outcomes. To understand the complicated relationships between income, social resources, and healthcare use, a systems approach is helpful. This essay explains why applications of systems thinking to income and social protection as factors that affect health equity are valuable and worthwhile. To get around upstream socioeconomic barriers to access, it explains how looking at things from a systemic point of view can lead to new policies. Essential suggestions focus on working together across sectors and increasing people’s abilities to put systems-based solutions into action. Overall, this paper shows how practical systems methods are for figuring out the many things that create barriers to care and creating unified programs that improve health equity.

Complexity of the Social Determinant

Income and social protection are two of the most important social determinants of health. Because they are reductionist, traditional methods often do not do enough to fix health disparities caused by these factors. By only focusing on specific aspects, like behaviours or healthcare provision, traditional models do not take into account how social determinants are linked and have many elements (Islam, 2019). As a result, they keep disparities going instead of fixing them. Instability in income and a lack of social protections are linked to harmful health outcomes in a cycle, but linear measures only address symptoms and not causes (Hillier-Brown et al., 2019).

In the same way, welfare benefits that do not include skill-building or community growth do not help people become self-sufficient. Instead, they put people under constant stress, which is terrible for their health. Fragmented decision-making wastes time and money trying to solve problems that are all linked.

As an example, let’s look at a situation where a lot of people in a community with low incomes have long-term illnesses. The traditional approach might involve putting in place health education programs that focus on people’s living choices, like encouraging them to eat better and exercise more. However, this does not deal with root causes.

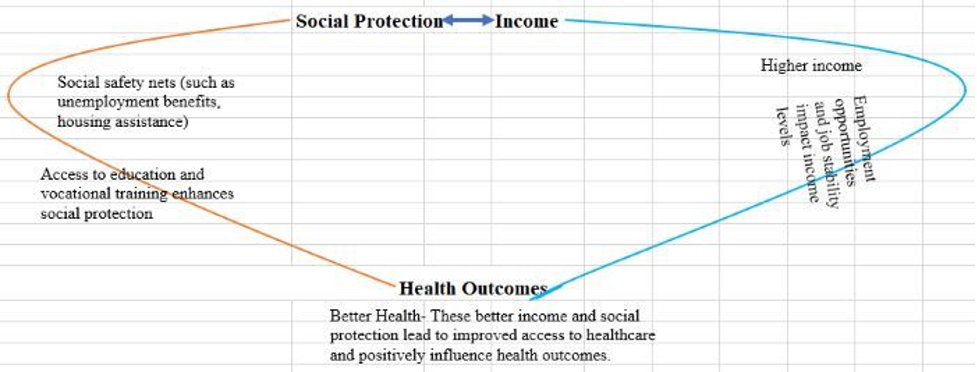

Systems thinking, on the other hand, helps people understand how complicated things are by mapping out many-sided problems to find points of high leverage for action. Tracing barriers to financial access and cumulative stress loads reveals policy, program, and relationship opportunities to systematically ease pressures that make things worse (Glenn et al., 2020). When job paths lead to higher incomes, barrier-free healthcare access, and health literacy support work together, they can break negative cycles that exacerbate problems. Human needs are the same for everyone, so setting priorities together that focus on health fairness requires coordinated efforts from different areas. Achieving long-lasting wins is possible by removing obstacles to opportunities.

Rationale for Systems Thinking

According to Morgan et al. (2023), the best way to look at the social drivers of health is through a systems-thinking approach. Systems thinking is increasingly being used as an approach to deal with those SDH struggles more effectively. This can demonstrate how various socioeconomic factors impact community health and how these factors impact one another. Systems thinking offers conceptual models that show how health results are dynamically linked to things like wealth, social protection, healthcare access, transportation, nutrition, and other social determinants. This is different from reductionist frameworks that focus on isolating variables. In social systems, interactions and loops that go both ways create new traits that aren’t clear when parts are looked at separately.

Take the example of how losing a job can set off a chain reaction that makes a chronic illness worse and leads to worse health results. When someone loses their job, they often also lose their health insurance. A lot of people can’t get or afford the medicines, care, and preventative services they need to properly handle long-term conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure as they do not have affordable insurance. This creates a cycle where things keep getting worse. Systems thinking can see these loops and strings of causal links that traditional linear analysis cannot. By looking at things like synergies, ripple effects, and unintended outcomes, systems thinking helps us fully understand the social and structural factors that impact public health (Johnson et al., 2018). These insights are more than just numbers; they show places with a lot of influence and weak spots where policy or program changes could make a difference. To make unified plans that can effectively and permanently enhance social situations, it is essential to know what the community is like and what the problems are. For financial protection, service access, and public health, this will be a good thing.

Strengths and Benefits of Systems Thinking

When social and economic problems cause differences in health, a systems thinking approach can help us figure out what those differences are and how they are connected. Visual mapping shows how financial security and access to health care are related to systems like housing, transportation, and jobs that are close by. Indirect but strong leverage points for improving equity are found this way (ALDERWICK & GOTTLIEB, 2019). Systems tools show how one action can have results that have other actions. For example, policies that reduce poverty may lead to more people using healthcare. More innovative actions are encouraged by modelling complex dynamics.

Participatory methods that include a range of voices make sure that systems thinking and policies reflect the views of people who live and work in the area. Getting affected groups involved leads to solutions that are culturally aware and fit the area. Working together across fields improves learning across disciplines and the creation of coordinated interventions (Haagh & Rohregger, 2019). For example, programs that help underserved groups figure out how to use health services could be shaped by partnerships with financial counsellors. When people understand shared systems, their mental models and behaviours are in sync.

Systems thinking’s main strength is that it encourages iterative methods that work well for making policies that change over time (Smith et al., 2024). On the other hand, systems understand that complicated issues change over time, unlike linear models. It is possible to respond better because of built-in feedback loops that let you think again and change course as needed. For systems, simulation tools are helpful because they help people think of problems that might happen before they do. So, flexible rules can be made that can be used when goals change, like when people’s incomes go up and down or when they become eligible for social support.

The WHO’s approach to systems thinking for health is directly in line with the ways that systems thinking is participatory, iterative, and adaptive (Vallières et al., 2022). This framework stresses the importance of involving a wide range of stakeholders, making policies that work together, and creating feedback loops so that methods are always being evaluated and changed based on new evidence. This method, which includes everyone, fits with the WHO concept of stakeholder engagement and participatory policymaking. Being able to adapt to new scenarios is important to the WHO because they want to promote “adaptivity, iteration, and continuous learning.” Using simulations to plan for problems is a good example of what the WHO means by “anticipating unintended consequences” before they happen.

Strengthening the Health System

Addressing social issues that affect health, like poverty, schooling, and the environment, requires people from different fields to work together and have a complete understanding of the system. A systems view shows how health is linked to its social and economic surroundings for more complete answers. People can get the necessary care and make enough money to pay for it by connecting social aid programs with health services. Aiding poor communities with their social and financial challenges is also a clear example of systems thinking (Haynes et al., 2020).

System thinking can help policymakers figure out better ways to deal with the economic and social issues that affect health. The places where people live, work, and go to school can have a significant impact on why their community is healthy. Make laws that deal with substantial issues like poverty. This will stop diseases from spreading and people from getting care. Along with policy research, systems thinking can help us understand how complicated society is. When you look at the system as a whole, you can see how policies that focus on specific parts, like food stamps or parental leave, have many positive effects on society, such as making it easier for people to get medical care.

Taking a systems approach to social variables lets healthcare systems get more robust by allowing people to work together to invest in them. Focusing on a single problem doesn’t always work when you think about how health determinants are connected (Kleinman et al., 2021). For example, making it easier for more people to get health insurance won’t help if problems like not having enough money, transportation, or knowledge about health care still exist. Systems thinking shows where multi-sectoral answers are needed based on how people live in groups (Thomas et al., 2020). The system lets various groups of people work together to make coordinated changes that take important local factors into account. Utilising a whole-person method encourages teamwork, makes the most of limited resources, and builds systems that work together for everyone’s benefit.

Engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

To use culturally sensitive systems thinking, people from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups need to be involved naturally. This means working together to create interventions using frameworks from Indigenous knowledge, figuring out complicated historical contexts, and making sure that the community drives involvement (Pearson et al., 2020). It is essential to work closely with Elders, healers, culture brokers, and advice groups. Their knowledge and oversight make sure that planned projects are in line with self-identified needs, cultural norms, and practices. Consensus-building and respectful conversation help people feel more in control of their lives and lead to new ideas that are better for Indigenous people (Reddel et al., 2022). For systems-based solutions to be moral, practical, and effective, they need to include ways to include and value the voices of First Nations people as equal partners, not just as study subjects.

Innovative Policies and Initiatives

A systems thinking approach helps come up with new policies by looking at the many factors and feedback loops that keep socioeconomic health disparities going from a full-picture point of view. This encourages coordinated actions that go beyond separate government areas to help communities get better by stabilising their finances, making it easier for them to find care, teaching them more about health, and removing barriers (Owusu-Addo et al., 2018). Computational mapping of the causes of inequality reveals policy levers that are not being used enough. This leads to innovative modifications based on social justice and equity principles that are not taken into account by approaches that remain unchanged.

It’s more accessible for everyone involved to work together to make intelligent policies that address health equity when people use systems thinking. When officials work with groups that are having social and economic problems, they learn important things that help them make better decisions. Interventions that are based on real-life events are more useful when they use participatory methods. Systems tools let partners from various fields work together and join their efforts (Genn, 2019). People can be more creative and agree on how to solve problems that touch many things when they brainstorm with other people. Lawmakers could work with transportation officials to fix issues that make it harder for people whose income changes often to get health care. Innovative policies that address the underlying socioeconomic barriers to healthcare access and social safety can be made possible through inclusive co-creation.

Lastly, systems thinking is flexible, which means it can be used to change programs that are not working and spread models that do. Systems tools can quickly move resources around and adjust methods to keep things fair as societal conditions and population needs change. The systems view does not try to lock down disadvantaged groups in rigid structures. Instead, it stays flexible and open, driven to improve communities through coordinated efforts in areas like health, economics, infrastructure, and freedom. It gives solid advice on how to make long-term investments in care and chance.

Systems thinking is important because it gives us a way to plan structured interventions, like the 10-step process (define the problem, find its causes, come up with answers, etc.). For instance, by following these steps based on proof, a policy could be made to remove barriers to healthcare access (Whelan et al., 2023). This would allow for constant improvement, from root cause analysis to pilot testing. Following set rules makes sure that the programs that are made use system principles in ways that have been shown to turn ideas into real-world solutions that work in different situations. Overall, systems thinking helps with methodical growth, from figuring out the problem to putting the solution into action.

Recommendations for Implementation

- Engagement with Diverse Stakeholders: Form cross-sectoral teams (health, economics, infrastructure, and community) to work on strategy, mirroring the WHO’s emphasis on diversified “engagement and participation”(Rosemary Kennedy Chapin & Lewis, 2023). Encourage collaboration and diversity in policymaking by forming interdisciplinary task teams, ensuring a thorough grasp of the interconnected concerns of income, social protection, and health.

- Comprehensive Problem Definition: Follow the WHO’s advice on problem definition by performing a complete examination of the social determinants of health, with a focus on income and social protection.

- Iterative Solution Generation: Adopt the WHO’s iterative approach, which encourages participatory techniques and continual communication with stakeholders (Vallières et al., 2022). Develop policies and solutions based on systems thinking principles, taking into account the complex relationships and feedback loops found during the problem characterization phase.

- Flexible Implementation Planning and Monitoring: To align with the WHO’s request for adaptivity and continuous learning, incorporate flexibility into the implementation planning process (Vallières et al., 2022). Use systems thinking to predict unintended outcomes, and simulation techniques to prepare for shifting conditions.

References

ALDERWICK, H., & GOTTLIEB, L. M. (2019). Meanings and Misunderstandings: A Social Determinants of Health Lexicon for Health Care Systems. The Milbank Quarterly, 97(2), 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12390

Genn, H. (2019). Mitigating the Social Determinants of Health through Access to Justice Get access to Arrow. Current Legal Problems. https://doi.org/10.1093/clp/cuz003

Glenn, J., Kamara, K., Umar, Z. A., Chahine, T., Daulaire, N., & Bossert, T. (2020). Applied systems thinking: a viable approach to identify leverage points for accelerating progress towards ending neglected tropical diseases. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00570-4

Gunawardena, H., Voukelatos, A., Nair, S., Cross, S., & Hickie, I. B. (2023). Efficacy and Effectiveness of Universal School-Based Wellbeing Interventions in Australia: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(15), 6508–6508. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20156508

Haagh, L., & Rohregger, B. (2019). Universal basic income policies and their potential for addressing health inequities: transformative approaches to a healthy, prosperous life for all. Iris.who.int. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/346040

Haynes, A., Rychetnik, L., Finegood, D., Irving, M., Freebairn, L., & Hawe, P. (2020). Applying systems thinking to knowledge mobilisation in public health. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00600-1

Hillier-Brown, F., Thomson, K., Mcgowan, V., Cairns, J., Eikemo, T. A., Gil-Gonzále, D., & Bambra, C. (2019). The effects of social protection policies on health inequalities: Evidence from systematic reviews. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 47(6), 655–665. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48624295

Islam, M. M. (2019). Social determinants of health and related inequalities: Confusion and implications. Frontiers in Public Health, 7(11), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00011

Johnson, J. A., Anderson, D. E., & Rossow, C. C. (2018). Health Systems Thinking: A Primer. In Google Books. Jones & Bartlett Learning. https://books.google.co.ke/books?hl=en&lr=&id=HJFyDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Systems+thinking+helps+us+fully+understand+the+social+and+structural+factors+that+affect+public+health+by+taking+into+account+things+like+ripple+effects

Kleinman, D. V., Pronk, N., Gómez, C. A., Wrenn Gordon, G. L., Ochiai, E., Blakey, C., Johnson, A., & Brewer, K. H. (2021). Addressing health equity and social determinants of health through Healthy People 2030. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 27(6). https://doi.org/10.1097/phh.0000000000001297

Morgan, M. J., Stratford, E., Harpur, S., & Rowbotham, S. (2023). A Systems Thinking Approach for Community Health and Wellbeing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-023-09644-0

Owusu-Addo, E., Renzaho, A. M. N., & Smith, B. J. (2018). Cash transfers and the social determinants of health: a conceptual framework. Health Promotion International, 34(6), e106–e118. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day079

Pearson, O., Schwartzkopff, K., Dawson, A., Hagger, C., Karagi, A., Davy, C., Brown, A., & Braunack-Mayer, A. (2020). Aboriginal community controlled health organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of aboriginal and torres strait islander peoples in australia. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09943-4

Raghupathi, V., & Raghupathi, W. (2020). The influence of education on health: An empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015. Archives of Public Health, 78(1).

Reddel, T., Hand, K., & Lata, L. N. (2022). Influencing Social Policy on Families through Research in Australia. Family Dynamics over the Life Course, 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_14

Rosemary Kennedy Chapin, & Lewis, M. (2023). Social Policy for Effective Practice. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003273479

Smith, N., Georgiou, M., Jalali, M. S., & Sébastien Chastin. (2024). Planning, implementing and governing systems-based co-creation: the DISCOVER framework. Health Research Policy and Systems, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-023-01076-5

Thomas, S., Sagan, A., Larkin, J., Cylus, J., Figueras, J., & Karanikolos, M. (2020). Strengthening health systems resilience: Key concepts and strategies. Europe PMC. https://europepmc.org/article/med/32716618

Vallières, F., Mannan, H., Kodate, N., & Larkan, F. (2022). Systems Thinking for Global Health: How can systems-thinking contribute to solving key challenges in Global Health? In Google Books. Oxford University Press.

Whelan, J., Fraser, P., Bolton, K. A., Love, P., Strugnell, C., Boelsen-Robinson, T., Blake, M., Martin, E., Allender, S., & Bell, C. (2023). Combining systems thinking approaches and implementation science constructs within community-based prevention: a systematic review. Health Research Policy and Systems, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-023-01023-4

write

write