Introduction

In the last few decades, the issue of borders between countries and migration politics has become very precarious. As of 2018, the world had 65.5 million forcibly displaced people, 10 million stateless, and 22.5 million refugees, making these some of the most important issues than ever (Gessen, 2018, Par. 2). These people can be said to exist nowhere as they cannot call any country or place in the world home. This has happened in a world with many human rights statutes and policies, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), that are, in theory, enjoyed by all people. This has led to a lot of debate on whether there is a class of people that qualifies to enjoy human rights and another that cannot. This debate has centred on the concept of the ‘right to have rights.’

This paper focuses on explaining what the ‘right to have rights is and how it plays out in This paper focuses on explaining what the ‘right to have rights’ is and how it plays out in contemporary border and migration politics. In defining the concept of the ‘right to have rights,’ different literature including the works of Hannah Arendt will be used. While there are a number of cases that can be used to explain how the right to have rights plays out in contemporary border and migration politics, the case study on the new nationality and borders bill in the UK will be used.

Defining the ‘Right to Have Rights’ and Overview of the Case

The concept of the right to have rights was first introduced by Hannah Arendt over half a century ago. From the works of Arendt, it became clear that some rights belong to some people and not others. Arendt (1973, p.296-97) noted that the ‘right to have rights’ “means to live in a framework where one is judged by one’s actions and opinions and a right to belong to some kind of organized community.” As Gessen, (2018, Par. 2), “the phrase summed up her scepticism about the concept of human rights—those rights that, in theory, belong to every person by virtue of existence.” This is what gives one the right, in reality, to be guaranteed all other rights such as most of those contained in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). For instance, article 13 of the UDHR states that: “(1) Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state and (2) Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country” (United Nations, n.d.). However, this cannot happen without a visa or belonging to a known state. Yet article 15 of the UDHR guarantees the right to nationality on everyone, including granting all the ability to change nationality whenever they wish (United Nations, n.d). Thus, the right to be a citizen is simply the right to have rights.

Regarding the case of the UK’s new nationality and borders bill now the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, there is a lot of focus on the criminalisation of asylum-seeking behaviour in the region, something that will lead to increased loss of the ‘right to have rights’ to many people in the region (Legislation.gov.uk, 2022). This bill sought to empower the government to infringe on the rights of minorities when it feels there is a public interest to do so, meaning it will be opening the door to a human rights violation. With most provisions of the act coming to force in June 2022, it will amplify the denial of the ‘right to rights’ to many, as seen in section 11 of the act which places a lot of conditions for one to be awarded citizenship, negating the spirit of the UDHR (Legislation.gov.uk, 2022). This case is chosen for the study because it is a good representation of how the ‘right to have rights’ plays out in contemporary border and migration politics. In this case, the UK’s new nationality and borders bill is a current issue that highlights the contemporary interplay between the right to have rights and border and migration politics.

How the ‘Right to Have Rights’ Plays Out in Contemporary Border and Migration Politics

One way how the ‘right to have rights’ plays out in contemporary border and migration politics is by making human rights no longer natural or universal to all by being human beings. Section 11 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 discriminates against people based on age and places a lot of requirements for one to be given citizenship. Yet, existing human right laws discourages any form of discrimination against any person and any interference with their enjoyment of human rights (United Nations, 2013, p.14). While the UDHR is the main human rights policy document globally, it seems that the ‘universal’ aspect in its first letter was a mistake as these rights are no longer universal. This Nationality and Borders Act 2022 has proven that the right to be awarded citizenship is not universal and one does not get it by virtue of birth. As Arendt (1973, p.273) noted, such violation of human rights in which most EU countries ignored the provision of the League of Nations indicated that the ultimate decision to protect the right to have rights rested on other human beings. This led to an increased number of people described as ‘illegal immigrants’ and stateless making them ‘symbolically eliminated’ in political activities (Krause, 2008, p.331). In the case of the UK, the UK new nationality and borders bill, the enactment of a bill that fails to observe the doctrine of the UDHR indicates that these rights are not universal. In addition, the discriminatory UK nationality and borders bill that comes with placing tiers on refugees depending on their country of origin as per section 12 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 and pushing for their deportation to a country they have never known shows how the universality concept of UDHR is misplaced (Brentnall, 2022, Par. 1). Thus, the ‘right to have rights plays out in the current border and migration politics by placing the universality aspect of ‘citizenship under siege.

In addition to negating the universality aspect, the ‘right to have rights’ also plays out in contemporary border and migration policing by placing unnecessary requirements such as a visa for anyone to move to the UK. This has catapulted the criminalisation of the movement of migrants from certain countries whose migrants are perceived to be insecure. For one to be given a visa to visit or reside in the UK, s/he has to go through a lengthy visa issuance process that may take years to be finalized. This visa requirement, in essence, negates the doctrine of the UDHR especially article 15 which gives a right to anyone to change nationality to any country of wish. To make it worse, people from some countries that are perceived to harbour terrorists or which are not in good diplomatic relations with the UK have little or no chance to be given residence status in these countries. This brings a different dimension to the right to have rights discourse and immigration, introducing a group that has citizenship status and belongs to a political group yet lacks the fundamental right to rights in other countries (Oudejans, 2019, p.450). In the case of the UK new nationality and borders bill, for example, those who face the threat of being deported to Rwanda are asylum seekers who are perceived inadmissible in that they cannot be returned to the country of origin given the exit of the UK from the European Union (EU), with the process to be followed remaining very opaque as seen in article 9 of the bill (Lindsay, 2022, Par. 6). In D4 -v- Home Secretary, the court of appeal in UK held that the government cannot strip off the citizenship of an individual without notice as per the provisions of the British Nationality Act 1981, something that the government wants to ensure it can do if article 9 of the UK new nationality and borders bill goes through (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary, 2022). While these people would have been treated differently if the UK was in the EU, the new changes point to a deteriorating human rights situation and an amplification of the right to have rights concept. Thus, the right to have rights plays out very well in how migrants are issued visas and residence in the countries they migrate to.

The right to have rights also plays in the current migration and border politics through the increased political activism and struggles of the perceived minority groups, hence becoming an important tool in challenging the new Nationality and Border Act 2022. The verb “to have” does not guarantee or indicate something that must happen. Lida Maxwell, stated in Gessen (2018, Par. 8) argued that ‘to have’ is not a verb of possession, adding that it can be taken to mean “to participate in staging, creating, and sustaining (through protest, legislation, collective action, or institution building) a common political world where the ability to legitimately claim and demand rights becomes a possibility for everyone.” In this case, those who would have such rights must fight to get them as these rights are not to be gained by merely being an individual, a common occurrence in the current political world (Degooyer & Hunt, 2018, Par. 12). In the UK, the new nationality and borders bill has resulted to a number of protects in the UK in recent months, with those at the risk of becoming second-class citizens upon the enactment of the bill that gives the government power to act on border and nationality issues that it perceives to have ‘public interest’ being on the lead (Sivathasan, 2022, Par. 10). If events such as the loss citizenship without major reasons for people in the UK is something to go by, then the future of immigration and border politics is likely to be impacted greatly (Shah, 2022, Par. 1). In the courts corridors, the UK Supreme Court in AO v Secretary of State for the Home Department what is also referred as PRCBC that the high fees charged for citizenship registration that is unaffordable to many are legal and the increased campaigns by the Project for the Registration of Children as British Citizens (PRCBC) highlight how gaining the right to have rights is a struggle for many, something that will be aggravated by the UK new nationality and borders bill (Jacob-Owens, 2022, Par. 1). Such protects epitomizes the new play of right to have rights in border and nationality conflicts that has now underscored the need to fight in order ‘to have’ basic human rights that come with nationality and citizenship. The ‘right to have rights’ cannot come without a struggle that seems to pit the perceived second class against the white supremacists. This struggle creates a very precarious environment in contemporary border and migration politics, with high levels of discrimination against some races being seen. Thus, the right to have rights plays out in border and migration politics today by increasing struggles in different ways such as legal battles and protests to actualise the ‘to have.’

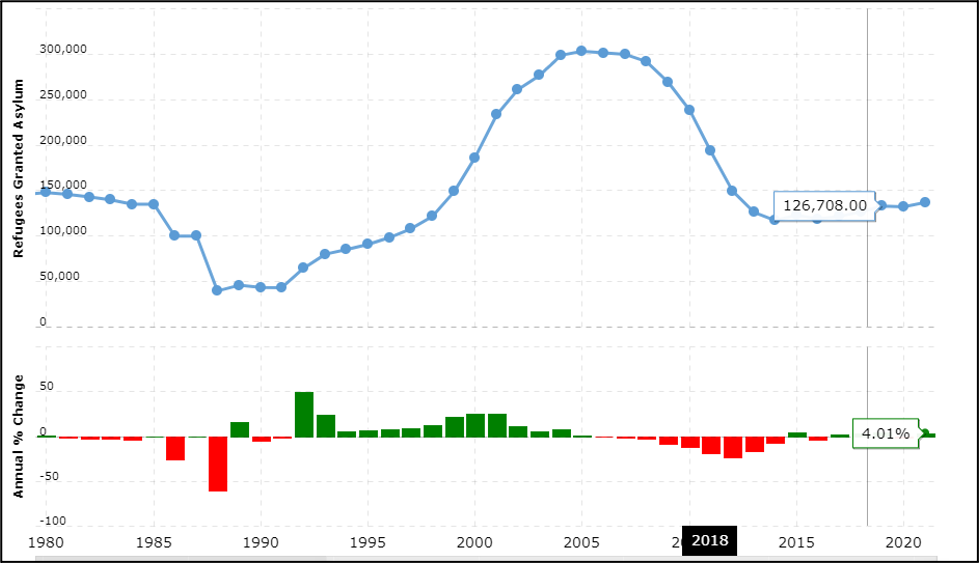

In addition, the right to have rights plays in today’s border and migration politics in that there is arguably a superior race in the UK that has an automatic ‘right to have rights’ before other races, a situation that will be amplified with the new bill. In the UK for instance, the new nationalism and borders bill is, in disguise, aimed at protecting a superior race that white supremacists think is under siege. According to Norris (2021, Par. 3), in reaction to the UK parliament’s nod to the bill “it is shocking, but perhaps not surprising. In the UK today, immigration policy is a continuation of British colonial power” adding that “it clear that British politics is deeply embedded in the ideology of white nationalism” (Par. 1). The classes of citizenship have characterised the UK political environment for years with the White British citizens getting permanent irrevocable citizenship while minority races have always been accorded citizenship that can easily be lost (Webber, 2022, p.75). The Nationality and Borders Act 2022 is an amplification of this status quo where some races who are considered inferior will be discriminated against and thus denied their ‘right to have rights.’ The white supremacists still have the view that some people belong to the colonized, a status that they believe should not change. To achieve this, the government has painted a picture of a very bad situation in which the number of asylum seekers has significantly increased, hence the need for urgent action. The bill is thus seen to be the solution. However, the situation is not as bad as painted by the government, as the number of asylum seekers has not increased significantly as shown in figure 1 below, making it hard to understand the motive behind the bill (Macrotrends, 2022). This action denies asylum seekers the ‘right to have rights’ such as belonging to another country as enshrined in the UDHR and other international doctrines. Having moved from their countries due to things such as war, they are likely to remain stateless if they do not fit into the conditions set out in the bill. Furthermore, they risk falling into modern-day slavery as the bill reduces protection given to refugees.

Figure 1: Refugees Granted Asylum in the UK. Source: Macrotrends (2022).

Conclusion

While the concept of the ‘right to have rights was introduced over half a century ago, it is still very relevant today. As indicated in the paper, the ‘right to have rights’ means the right to belong to a political society or to be a citizen of a recognized state as this is the minimum base for one to enjoy common human rights including those under the UDHR. As shown in the case of the UK new nationality and border bill, there is a perceived superior race epitomized by the increased white nationalism that has subjected other perceived minority races to a struggle to gain the ‘right to have rights.’ In this case, minorities who have been denied the ‘right to have rights’ are in an unending struggle, characterised by protests and legal battles. Unfortunately for them, the courts seem not to help in guaranteeing this basic right as seen in the case of the UK Supreme Court in AO v Secretary of State for the Home Department where the court did not assure the ‘right to have rights.’ These recent developments indicate a further struggle in making human rights conventions relevant and probably an indication that existing human rights doctrines need a review to guarantee the ‘right to have rights.’ The centre of this struggle is the borders of different countries, with current politicians using it to their advantage. Thus, the ‘right to have rights’ plays out in contemporary border and migration politics in different ways.

References

Arendt, H., 1973. The origins of totalitarianism. HarperCollins.

Brentnall, B., 2022. How Britain’s new laws doubly criminalise Black, Asian and Gypsy people. Open Democracy. [Online]. [Accessed 11 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/police-bill-nationality-borders-parliament-protest-ethnic-minority-activists/

Courts and Tribunals Judiciary., 2022. D4 -v- Home Secretary. [Online]. [Accessed 06 December 2022]. Available from: https https://www.judiciary.uk/judgments/d4-v-home-secretary/

Degooyer, S., and Hunt, A., 2018. The right to have Rights. Public Books. [Online]. [Accessed 07 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.publicbooks.org/the-right-to-have-rights/

Gessen, M., 2018. “The right to have rights” and the plight of the stateless. The New Yorker. [Online]. [Accessed 06 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/the-right-to-have-rights-and-the-plight-of-the-stateless#:~:text=Sixty%2Dnine%20years%20ago%2C%20Hannah,person%20by%20virtue%20of%20existence.

Jacob-Owens, T., 2022. British citizenship as a non-constitutional status: The UK Supreme Court ruling in PRCBC. Global Citizenship Observatory. [Online]. [Accessed 11 December 2022]. Available from: https://globalcit.eu/british-citizenship-as-a-non-constitutional-status-the-uk-supreme-court-ruling-in-prcbc/

Krause, M., 2008., Undocumented migrants: An Arendtian perspective. European Journal of Political Theory, 7(3), pp. 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474885108089175

Legislation.gov.uk., 2022. Nationality and Borders Act 2022. [Online]. [Accessed 08 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/36/contents

Lindsay, F., 2022. U.K. immigration bill threatens millions of ethnic minority Britons’ citizenship rights. Forbes. [Online]. [Accessed 08 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/freylindsay/2022/02/08/uk-immigration-bill-threatens-millions-of-ethnic-minority-britons-citizenship-rights/

Macrotrends., 2022. U.K. Refugee Statistics 1960-2022. [Online]. [Accessed 08 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/GBR/united-kingdom/refugee-statistics

Norris, M., 2021. The nationality and borders bill is a legacy of empire. Byline Times. [Online]. [Accessed 10 December 2022]. Available from: https://bylinetimes.com/2021/12/13/the-nationality-and-borders-bill-is-a-legacy-of-empire/

Oudejans, N., 2019. The right not to have rights: A new perspective on irregular immigration. Political Theory,47(4), pp. 447–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591718824071

Shah, S., 2022. ‘Maximum suffering.’ A man stripped of his citizenship sheds light on the potential impact of the U.K.’s nationality bill. Time. [Online]. [Accessed 07 December 2022]. Available from: https://time.com/6146655/uk-citizenship-nationality-immigration-bill/

Sivathasan, N., 2022. Nationality and borders bill: Why is it causing protests? BBC News. [Online]. [Accessed 11 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-59651523

United Nations., 2013. Migration and human rights: Improving human rights-based governance of international migration. [Online]. [Accessed 07 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Migration/MigrationHR_improvingHR_Report.pdf

United Nations., n.d. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. [Online]. [Accessed 06 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights#:~:text=Article%2013,to%20return%20to%20his%20country.

Webber, F., 2022. The racialisation of British citizenship. Race & Class,64(2), pp. 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063968221117950

write

write