Abstract

Selection and development of suppliers in the business environment of the contemporary dynamic global setup is increasingly essential for operational efficiency, a sense of resilience in the supply chain, and the sustainability of an organisation. This paper critically analyses emerging trends and technological advancements shaping future criteria for the selection of suppliers. Sustainability and innovation are some of the contemporary considerations to be added to traditional determinants like cost, quality, and reliability. The focus of organisational scrutiny has shifted to suppliers with operational agility and responsiveness. A key consideration is sustainability against backdrops of organisations coming under pressure to reconfigure the supply chain with environmental and ethical goals. With their innovative and sustainability standards, global firms will benchmark how organisations select suppliers in the future. Therefore, the future selection criteria would have to look for international value chain complex suppliers who address critical challenges such as supply chain complexity, cultural disparities, and geopolitical risks. Moreover, the sustainability considerations will take a higher ground, including environmental stewardship and ethical sourcing practices within the supplier selection domain.

Introduction

Operational efficiency within the supply chain is a vital tool used to achieve its goals, and the desired product quality and resilience in the supply chain are targeted organisational strategies. The selection and development of the supplier come first in this strategy. At the same time, more businesses are connected in a dynamic global environment with a broader range of criteria, increasing choices and shaping suppliers to respond to rising challenges and opportunities. This essay critically discusses what may come to be the leading criteria that would change practices in years to come. While cost, quality, and reliability have been the traditional mainstays, they are now accompanied by sustainability, innovation, and risk management. This move puts suppliers under pressure to ensure that they view themselves as a source of strategic advantage to firms, not just suppliers of materials but partners in enabling value creation and competitive advantage.

With artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the Internet of Things at the helm of tremendous technological advancements, the very aspect of supply chain management continues to be disrupted in revolutionary ways, enabling real-time visibility, predictive analytics, and collaboration capabilities across the supplier ecosystem. Suppliers using these technologies and increasing their operational agility and responsiveness will likely score very high on organisations’ selection radar. Secondly, sustainability will become part of supplier selection criteria in the future. So also, are the organisations under increasing pressure to align the supply chains with the sustainability goals as the expectations of society regarding the issues relating to environmental responsibilities and ethical sourcing continue to mount? Lastly, suppliers committed to being green, socially responsible, and having ethical practices will be better positioned to put up a competitive edge in the market. As torchbearers for supply chain management, global firms set standards for the industry and bring about innovation within the supplier network by acting as catalysts. Considering these, this essay seeks to determine the top criteria for supplier selection that the future holds.

Understanding Supplier Selection and Development

Supplier selection and development capture major features of the organisational supply chain, greatly impacting organisational effectiveness, competitiveness, and sustainability. As such, according to Kusi-Sarpong et al. (2021), the importance of supplier selection and development lies in being the means of success in an organisation’s operations. The argument is that those processes integrate to screen likely suppliers through pre-set criteria and strategic objectives. In addition, Jain, Singh, and Upadhyay (2020) add that, in supplier selection, potential suppliers are evaluated systematically, taking into account their abilities, reliability, and performance record and reflecting an organisation’s values and objectives. On the other hand, Jia, Stevenson, and Hendry (2021) discuss the development of suppliers as an internal strategy that focuses on enhancing relations with current suppliers to support continuous improvement and innovation. Selection is the systematic pick of the best potential suppliers who contribute effectively to the needs and objectives of an organisation.

While cost reduction remains a central focus, viewing supplier selection and development solely through an efficiency lens overlooks their deeper influence on building resilient and sustainable value chains. As Monczka et al. (2021) pointed out, focusing only on immediate cost benefits can create “myopic sourcing” – neglecting potential risks and ethical concerns associated with low-cost, unvetted suppliers. Conversely, investing in supplier development through collaborations, knowledge sharing, and joint product development unlocks long-term value by fostering innovation and enhanced capabilities (Le Dain & Merminod, 2014). This approach builds trust and transparency, as Asif et al. (2020) emphasised, leading to improved supplier performance that can even exceed what low-cost alternatives might offer. By recognising the dynamic interplay between selection and development, organisations can move beyond the “efficiency trap” and cultivate strategic partnerships that contribute to long-term sustainability, operational resilience, and enhanced competitiveness within their value chains.

Ensuring Operational Efficiency and Supply Chain Resilience

Importance of Operational Efficiency Toward Organizational Success

While supplier selection and development undoubtedly contribute to operational efficiency, their true value lies in fostering supply chain resilience, enabling organisations to navigate disruption without crippling their operations. This necessitates a critical shift in perspective, viewing these activities not as isolated cost-saving measures but as strategic investments in long-term sustainability and competitiveness. Bag et al. (2020) rightly emphasise the need for a robust selection process that identifies partners aligned with organisational quality, cost, and strategic objectives. This goes beyond price competitiveness, prioritising factors like reliability, ethical sourcing, and geographical diversification. As Kumar and Mishra (2022) point out, selecting suppliers based on the right blend of capabilities and reliability can mitigate risks, reducing lead times and operational costs even in volatile environments.

The role of supplier development extends beyond simply meeting immediate needs. Zavala-Alcívar et al. (2020) argue that ongoing development programs drive continual improvement in supplier performance and capabilities, fostering a culture of innovation and shared value within the supply chain. This argument is further supported by Benton et al. (2020), who highlight how diversifying the supplier base through strategic selection mitigates dependence on single sources, reducing vulnerability to unforeseen disruptions. The true power lies in integrating these activities, creating a synergistic effect that transcends mere efficiency gains. By strategically selecting resilient and adaptable suppliers and proactively investing in their development, organisations build a proactive shield against disruption, reducing dependence on single sources and fostering continuous improvement, ensuring suppliers remain competitive and agile in a dynamic business environment. Viewing supplier selection and development through the lens of operational efficiency alone provides a limited perspective. Instead, embracing their strategic role in building supply chain resilience empowers organisations to adapt to unexpected challenges, maintain operational continuity, and ultimately achieve long-term success in a turbulent global landscape. This holistic approach is no longer a luxury but a critical imperative for survival and competitive advantage in today’s interconnected world.

Relevance of International Value Chains

The increasingly interconnected and interdependent nature of international value chains (IVCs) compels organisations to adopt a nuanced and critical approach to supplier selection. Moving beyond mere cost reduction demands navigating a complex dance of diverse factors. As Bontadini and Saha (2021) aptly state, IVCs define the criteria used for supplier selection across industries, highlighting the interconnectedness that transcends national borders. These value chains weave together suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and service providers, adding value to products reaching global consumers (Antràs and Chor, 2022). However, globalisation’s promised land of specialised skills, cost reductions, and economies of scale (Luo, 2021) comes with many complexities. Patel (2023) underscores the crucial role of critical supplier evaluation in mitigating risks arising from diverse sources like geopolitical tensions, cultural nuances, regulatory hurdles, and logistical challenges. The very interconnectedness of IVCs necessitates strategic criteria for selecting dependable partners.

Consider a company leveraging global sourcing to access specialised skills and achieve scalability at low costs. However, this interconnectedness introduces complexities requiring careful evaluation of geopolitical and cultural differences alongside traditional cost and quality considerations. Organisations must master this multi-dimensional balancing act to ensure resilient and efficient cross-border supply chains (Monczka et al., 2021). Organisations can unlock significant benefits by strategically sourcing suppliers with the requisite capabilities and minimising associated risks through a comprehensive understanding of the IVC’s influence (Viser & Kymal, 2015). This understanding translates to enhanced efficiency, flexibility, and resilience in supply chain operations, enabling them to navigate the global market’s complexities and meet consumer demands effectively.

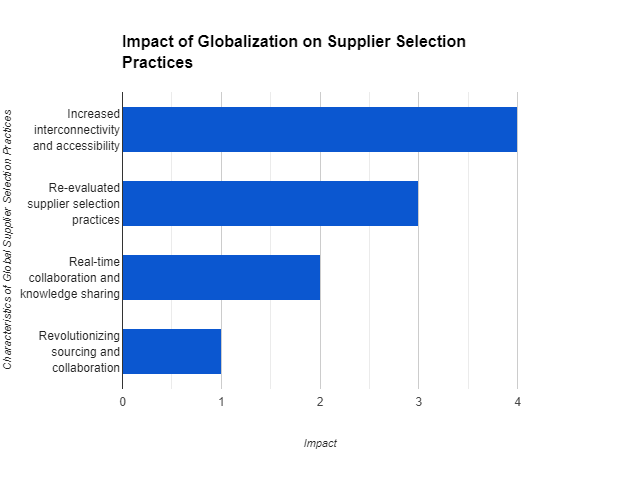

The dynamic nature of globalisation, characterised by increased interconnectivity and accessibility, fundamentally reshapes supplier selection practices. As Austin (2023) observes, globalisation offers unprecedented access to sourcing options worldwide, necessitating a continuous re-evaluation of traditional selection criteria to adapt to this evolving landscape. Seabrooke and Wigan (2022) further argue that any transformation impacting the global landscape influences supplier selection. Advanced communication, transport, and trade systems make global sourcing a reality. At the same time, collaboration platforms and digital tools enable real-time knowledge sharing and collaboration, which fosters a demand for more complex selection criteria focused on innovation capabilities, collaboration potential, and market dynamics.

This globalisation of supplier selection revolutionises how organisations approach sourcing and collaboration with partners. Increased connectivity and access to alternative sourcing options empower organisations to reimagine traditional selection criteria. Collaboration platforms and digital tools, as mentioned in Appendix B, go beyond merely facilitating knowledge transfer and real-time collaboration. They enable organisations to shift their focus towards assessing parameters like the supplier’s innovation capabilities and collaboration potential, reflecting the dynamism of global markets (Asif et al., 2020). With supplier selection practices evolving with global interconnectivity, organisations need strategies that leverage this interconnected and dynamic business environment (Dharmayanti et al., 2023). Such strategies enable them to benefit from informed collaboration and build resilient and adaptive supply chains. The crucial shift in focus from cost and quality to broader aspects like innovation and collaboration potential reflects the transformative impact of globalisation on supplier selection practices.

Dilemmas in Implementing International Value Chains

International Value Chains (IVCs) offer remarkable efficiency and cost advantages, weaving a seamless web of interconnectedness across borders. However, this intricate dance comes with ethical and environmental dilemmas that present organisations with a daunting balancing act between compliance and competitive advantage (Fan, 2023). Unveiling the tensions involved, exploring the evolving regulatory landscape, and critically evaluating alternative approaches are crucial steps towards navigating this challenging terrain and unlocking the strategic opportunities embedded within sustainability. The allure of low-cost production often leads organisations to source from regions with lax regulations and weak oversight (Yu & Zhao, 2022). In the garment industry, Bangladesh’s Rana Plaza disaster tragically exposed the human cost of prioritising price over ethical sourcing (Islam, Deegan & Haque, 2021). This pursuit of lower costs clashes with growing consumer demand for ethical and sustainable products. Organisations face the dilemma of maintaining competitiveness while meeting these evolving expectations. Stringent environmental regulations and ethical sourcing requirements are no longer distant threats but present realities. For instance, the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive mandates large companies to report on sustainability risks and impacts across their value chains (Kinderman, 2020). Such regulations push organisations to re-evaluate their sourcing strategies and invest in sustainable practices to avoid sanctions and reputational damage. This regulatory pressure can be a springboard for positive change. Organisations that proactively adopt sustainable practices gain a competitive edge.

Addressing IVC dilemmas requires collaboration beyond individual organisations. Stakeholder engagement through partnerships with NGOs, communities, and suppliers allows for shared perspectives and solutions (Liu et al., 2018). Multi-stakeholder initiatives like the Global Apparel Forum tackle industry-wide challenges like labour rights and environmental sustainability (Yu & Zhao, 2022). These collaborations provide platforms for knowledge sharing and collective action, fostering greater transparency and accountability throughout the value chain. However, these approaches have limitations. Stakeholder interests can diverge, making consensus difficult. Initiatives may need enforcement mechanisms, and their impact on smaller, less visible actors within the chain remains an ongoing challenge.

Integrating sustainability into the core of organisational strategy goes beyond mere compliance or risk mitigation. It presents a strategic opportunity for long-term value creation. Studies show that sustainable practices can save costs through resource efficiency and waste reduction (Mikhno et al. 2021). Consumers increasingly reward brands that align with their values, fostering brand loyalty and market differentiation. Additionally, embracing sustainability strengthens supply chain resilience by mitigating environmental and social risks, ensuring long-term stability and resource access (Silva, Pereira & Hendry, 2023). Ultimately, navigating the dilemmas within IVCs requires a critical lens beyond balancing compliance and cost. Recognising the evolving regulatory landscape and leveraging alternative approaches like stakeholder engagement can pave the path towards sustainable practices. Ultimately, embracing sustainability is an ethical imperative and a strategic opportunity for organisations to secure long-term competitive advantage, brand loyalty, and a resilient future within the interconnected global economy.

Importance of Sustainability in Supplier Selection

Sustainable considerations include environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and ethical sourcing practices, for which organisations mandate that suppliers be partners need sustainable suppliers. Shoukohyar and Seddigh (2020) emphasise the enhanced awareness by firms on the environmental print along the supply chain through more engagements with suppliers who emphasise sustainability. Barauskaite and Streimikiene (2021) go a step further to emphasise that gauging suppliers’ environmental performance should be based on their practices in environmental management, resource efficiency, and attempts at reducing carbon footprints. They further add that the evaluation of suppliers should be based on their practices socially and ethically, including the records of labour practices, human rights, and engagement programs for communities.

While acknowledging sustainable supplier selection’s environmental, social, and ethical benefits, a critical analysis reveals deeper complexities. True integration goes beyond superficial compliance and checkbox exercises. According to Farza et al. (2021), beyond cost reduction and efficiency, selecting suppliers based on environmental management, resource efficiency, and ethical practices can indeed drive innovation, enhance brand reputation, and create long-term stakeholder value. However, attributing these outcomes solely to “sustainable supplier selection” risks simplifying a nuanced issue. Factors like internal innovation culture, effective collaboration, and transparent communication play equally crucial roles (Abu-Rumman, 2021).

Further, the claim that sustainable sourcing assures “a lasting future” overlooks the limitations and challenges. Market dynamics, geopolitical factors, and competitor strategies can still pose significant threats, even with sustainable practices in place. The strategic advantage lies in understanding the systemic interplay between sustainability and broader business objectives (George & Schillebeeckx, 2022). Organisations must critically evaluate their entire value chain, identify vulnerabilities, and invest in targeted, sustainable practices that address specific risks and opportunities. This ensures long-term resilience and competitive advantage, not just compliance and reputation management.

Managerial Dilemmas in Implementing Sustainable Practices

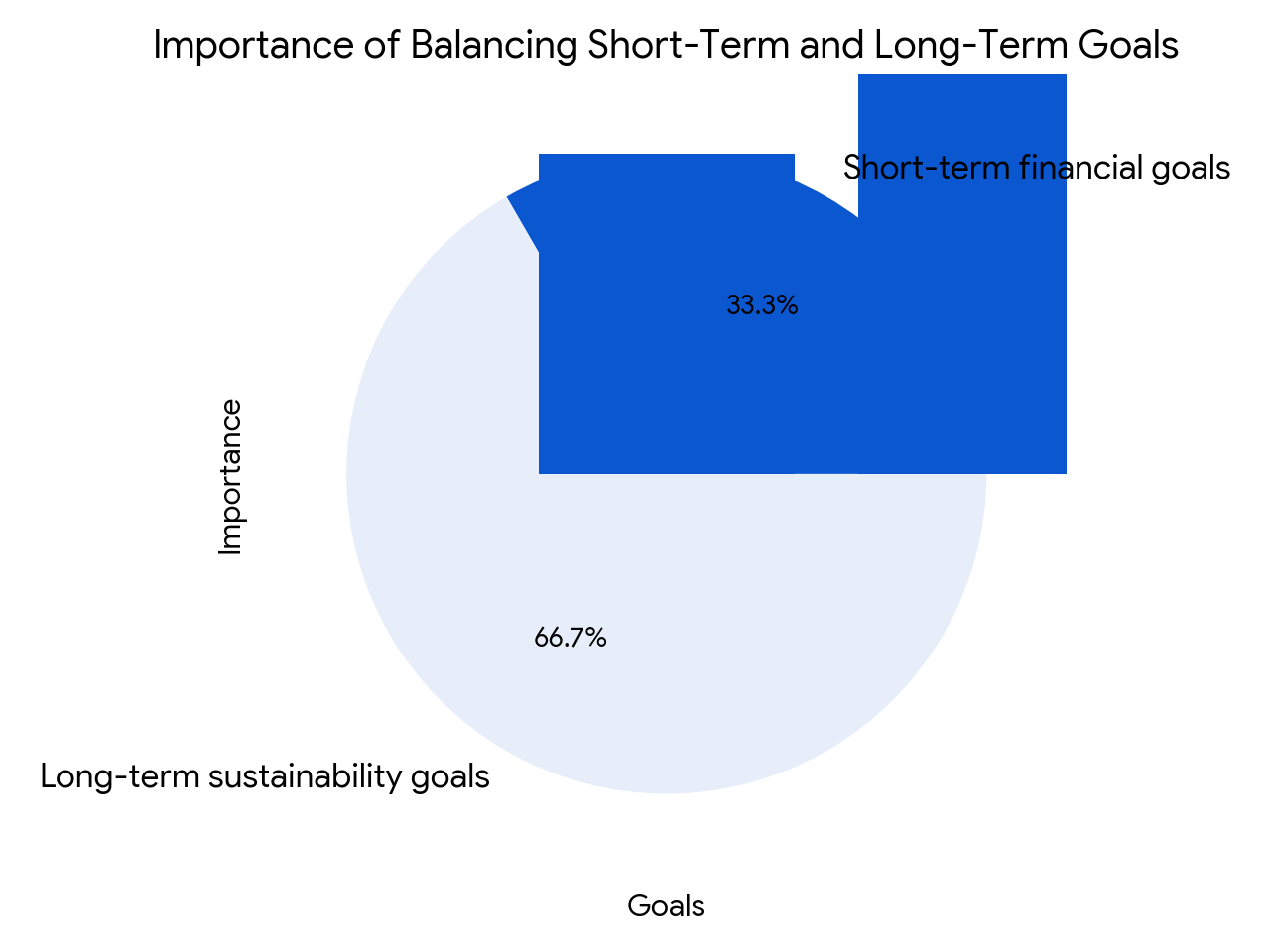

The main challenge for managers working in an organisation is to balance the short-term financial objectives with a long-term sustainability goal that requires delicate balancing and alignment from a strategic viewpoint. Haessler (2020) asserts the problem of the managers, generally, in combining short-term financial goals with sustainability goals in the long term, in which those in the leadership role must be sensitive to the strain that arises from immediate financial and long-term sustainability goals. Pot (2021) further elaborates that while sustainable initiatives have long-term benefits in the sense that they save costs and mitigate risks, they come with a cost upfront and have additional short-term costs. Besides, Pot (2021, p.56) further elaborates on the fact that there is always a trade-off between the sustainable sourcing practices of ethical sourcing and waste reduction, which might lead to an increased procurement cost or even investment in suppliers’ capacity-building and technology upgrades as will be explained further in Appendix A.

Managers must find ways of reconciling the often-competing demands of short-term financial objectives with longer-term sustainability goals. For instance, sustainability initiatives provide long-term benefits. However, they often imply some upfront investment with long payback periods, maybe even outside the lifetime of the purchasing manager, like investments to develop supplier capacity or to increase technology (Busco et al., 2017). An important consideration is balancing the perceived long-term benefits with the cost-benefit trade-offs in embarking on sustainability. Stakeholder engagement is crucial for building trust and keeping them informed: suppliers, employees, investors, and customers all rely on transparent dialogue with managers (Kaptein & Van Tulder, 2017). It is the management of that tension between the short-term financial objectives and long-term sustainability goals where the stakeholders’ strategic alignment and effective engagement lie. A manager can thus come to grips with the complex web of sustainability, ensuring both economic viability and environmental responsibility by prudent cost-benefit trade-offs for sustainability initiatives and enhanced transparency in information for stakeholders.

Top Criteria for Supplier Selection in the Future

Identifying the top criteria for supplier selection in the future necessitates exploring emerging trends, novel technologies, and changing stakeholder expectations, especially regarding sustainability, innovation, and risk management. According to Yasir Hayat Mughal et al. (2023), sustainability considerations like environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and ethical sourcing practices are increasingly cited as future aspects of supplier selection procedures. It is underlined that such suppliers that show responsibility and sustainability will attract more firms, so the trend in sustainability assessments and certifications will arise. According to the authors, with much innovation, adding digital technologies such as AI, blockchain, and data analytics would increase visibility and traceability within the supply chain to optimise its performance. Li et al. (2024) further underline that risk management in future supplier selection will be pivotal, especially against emerging geopolitical uncertainties, supply chain disruptions, and regulatory changes. It underscores a preference for resilient and flexible suppliers capable of jointly operating under market volatility conditions and enhancing this resiliency. Organisations must critically evaluate and collaborate to shape a sustainable future, not just predict it.

Upstream and Downstream Activities of Global Firms

International value chains (IVCs) weave a complex tapestry of interconnected activities, spanning the journey of a product from raw materials (“upstream”) to its final destination (“downstream”). Within this tapestry lies the opportunity to embed sustainability practices, not just as isolated efforts but as a holistic approach woven through the entire chain. Upstream, responsible sourcing sets the tone. Criteria like responsible sourcing, advocating for ethical labour practices and prioritising environmentally sound materials ensure a strong foundation (Salimian et al., 2020). Supplier development programs go beyond mere selection, empowering suppliers to adopt sustainable practices through capacity building and knowledge sharing. For instance, Patagonia’s collaboration with organic cotton farmers in India demonstrates the positive impact of such programs (O’Rourke & Strand, 2016).

Downstream, the focus shifts towards responsible product stewardship. Ethical marketing goes beyond promoting products; it educates consumers and fosters responsible consumption. Additionally, end-of-life product management ensures responsible disposal or even product rebirth through initiatives like Dell’s takeback and recycling program (Dell, 2023). Emerging at the forefront of sustainability is the circular economy, a closed-loop system minimising waste and maximising resource use. Nike’s “Move to Zero” program, aiming to eliminate waste and use recycled materials across its products, represents this shift (Nike, 2023). The interconnectedness of upstream and downstream activities is crucial. Unsustainable practices at any stage can undermine the entire chain’s efforts (Cattaneo et al., 2013). Embracing the circular economy further minimises waste and maximises resource use. By recognising the interconnectedness of these activities, companies can move beyond fragmented efforts and truly weave sustainability into the fabric of their entire value chain.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this essay has explored the evolving landscape of supplier selection criteria, highlighting the shift towards sustainability, innovation, and resilience in the face of dynamic global challenges. Traditional factors like cost and quality remain crucial, but integrating sustainability practices has become increasingly imperative, driven by growing stakeholder expectations and regulatory pressures. As organisations navigate the complexities of international value chains, strategic partnerships with suppliers prioritising ethical practices and environmental stewardship are paramount. Adopting digital technologies such as AI, blockchain, and data analytics offers opportunities to enhance supply chain visibility, traceability, and operational efficiency. However, international business managers need to recognise the holistic nature of sustainability, going beyond mere compliance to embrace long-term value creation and risk mitigation strategies. Recommendations for managers include fostering transparent communication with stakeholders, prioritising supplier development programs that promote sustainable practices, and integrating sustainability considerations into core business strategies. Embracing sustainability aligns with societal expectations, fosters innovation, enhances brand reputation, and contributes to long-term competitiveness in the global marketplace. By prioritising sustainability in supplier selection and development processes, organisations can build resilient, adaptive, and responsible supply chains that withstand disruption and drive sustainable growth in the future.

Bibliography

Abu-Rumman, A., 2021. Effective Knowledge Sharing: A Guide to the Key Enablers and Inhibitors. In Handbook of Research on Organizational Culture Strategies for Effective Knowledge Management and Performance (pp. 133-156). IGI Global.

Antràs, P. and Chor, D. (2022). Chapter 5 – Global value chains. [online] ScienceDirect. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1573440422000053.

Asif, M.S., Lau, H., Nakandala, D., Fan, Y. and Hurriyet, H., 2020. Adoption of green supply chain management practices through collaboration approach in developing countries–From literature review to conceptual framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 276, p.124191.

Austin, E.E., 2023. Going Global in the World Language Classroom: Ideas, Strategies, and Resources for Teaching and Learning with the World. Taylor & Francis.

Bag, S., Wood, L.C., Xu, L., Dhamija, P. and Kayikci, Y. (2020). Big data analytics as an operational excellence approach to enhance sustainable supply chain performance. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 153(1), p.104559. doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104559.

Barauskaite, G. and Streimikiene, D. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance of companies: The puzzle of concepts, definitions and assessment methods. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(1), pp.278–287. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2048.

Benton, W.C., Prahinski, C. and Fan, Y. (2020). The influence of supplier development programs on supplier performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 230, p.107793. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107793.

Bontadini, F. and Saha, A., 2021. How Do We Understand Participation in Global Value Chains? A Structured Review of the Literature. OFCE.

Busco, C., Fiori, G., Frigo, M.L. and Angelo, R., 2017. Sustainable Development Goals: Integrating sustainability initiatives with long-term value creation. Strategic Finance, pp.28-37.

Cattaneo, O., Gereffi, G., Miroudot, S. and Taglioni, D., 2013. Joining, upgrading and being competitive in global value chains: a strategic framework. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (6406).

Dell (2023). Dell – Free Consumer Takeback Services. [online] recycling.dell.com. Available at: https://recycling.dell.com/_Content/en-GB/ [Accessed 17 Feb. 2024].

Dharmayanti, N., Ismail, T., Hanifah, I.A. and Taqi, M., 2023. Exploring sustainability management control system and eco-innovation matter sustainable financial performance: The role of supply chain management and digital adaptability in Indonesian context. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(3), p.100119.

Dinh, V.D.M., 2021. Sustainability drivers and practices in Vietnamese manufacturing: a multiple-case study through the lens of the Sustainability Marketing Mix.

Fan, D., 2023. Managing Globalised and Deglobalized Supply Chains. In Managing Globalized, Deglobalized and Reglobalized Supply Chains (pp. 35-50). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Farza, K., Ftiti, Z., Hlioui, Z., Louhichi, W. and Omri, A., 2021. Does it pay to go green? The environmental innovation effect on corporate financial performance. Journal of Environmental Management, 300, p.113695.

George, G. and Schillebeeckx, S.J., 2022. Digital transformation, sustainability, and purpose in the multinational enterprise. Journal of World Business, 57(3), p.101326.

Haessler, P. (2020). Strategic Decisions between Short-Term Profit and Sustainability. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), p.63.

Islam, M.A., Deegan, C. and Haque, S., 2021. Corporate human rights performance and moral power: A study of retail MNCs’ supply chains in Bangladesh. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 74, p.102163.

Jain, N., Singh, A.R. and Upadhyay, R.K. (2020). Sustainable supplier selection under attractive criteria through FIS and integrated fuzzy MCDM techniques. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, pp.1–22. doi https://doi.org/10.1080/19397038.2020.1737751.

Jia, M., Stevenson, M. and Hendry, L. (2021). A systematic literature review on sustainability-oriented supplier development. Production Planning & Control, pp.1–21. doi https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2021.1958388.

Kaptein, M. and Van Tulder, R., 2017. Toward effective stakeholder dialogue.

Kinderman, D., 2020. The challenges of upward regulatory harmonisation: The case of sustainability reporting in the European Union. Regulation & Governance, 14(4), pp.674-697.

Kumar, R. and Mishra, R.S., 2020. Linking TQM Critical Success Factors to Strategic Goal: Impact on Organisational Performance. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng, 17, pp.1-13.

Kusi-Sarpong, S., Gupta, H., Khan, S.A., Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J., Rehman, S.T. and Kusi-Sarpong, H. (2021). Sustainable supplier selection based on industry 4.0 initiatives within the context of circular economy implementation in supply chain operations. Production Planning & Control, pp.1–21. doi https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2021.1980906.

Le Dain, M.A. and Merminod, V., 2014. A knowledge sharing framework for black, grey and white box supplier configurations in new product development. Technovation, 34(11), pp.688-701.

Li, Y.L., Tsang, Y.P., Wu, C.H. and Lee, C.K.M. (2024). A multi-agent digital twin–enabled decision support system for sustainable and resilient supplier management. Computers & Industrial Engineering, [online] 187, p.109838. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2023.109838.

Liu, L., Zhang, M., Hendry, L.C., Bu, M. and Wang, S., 2018. Supplier development practices for sustainability: A multi‐stakeholder perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(1), pp.100-116.

Luo, Y. (2021). New OLI advantages in digital globalisation. International Business Review, [online] 30(2), p.101797. doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101797.

Mikhno, I., Koval, V., Shvets, G., Garmatiuk, O. and Tamošiūnienė, R., 2021. Green economy in sustainable development and improvement of resource efficiency.

Monczka, R.M., Handfield, R.B., Giunipero, L.C. and Patterson, J.L., 2021. Purchasing & supply chain management. Cengage Learning.

Nike (2023). Nike Sustainability. Move to Zero. [online] Nike.com. Available at: https://www.nike.com/sustainability [Accessed 17 Feb. 2024].

O’Rourke, D. and Strand, R., 2016. Patagonia: Driving sustainable innovation by embracing tensions. The Berkeley-Haas Case Series. University of California, Berkeley. Haas School of Business.

Patel, K.R. (2023). Enhancing Global Supply Chain Resilience: Effective Strategies for Mitigating Disruptions in an Interconnected World. BULLET: Jurnal Multidisiplin Ilmu, [online] 2(1), pp.257–264. Available at: https://journal.mediapublikasi.id/index.php/bullet/article/view/3482.

Pot, W.D. (2021). The governance challenge of implementing long-term sustainability objectives with present-day investment decisions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 280, p.124475. doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124475.

Salimian, H., Rashidirad, M. and Soltani, E. (2020). Supplier quality management and performance: the effect of supply chain-oriented culture. Production Planning & Control, 32(11), pp.1–17. doi https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1777478.

Seabrooke, L. and Wigan, D. eds., 2022. Global wealth chains: Asset strategies in the world economy. Oxford University Press.

Shoukohyar, S. and Seddigh, M.R. (2020). Uncovering the dark and bright sides of implementing collaborative forecasting throughout sustainable supply chains: An exploratory approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 158, p.120059. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120059.

Silva, M.E., Pereira, M.M. and Hendry, L.C., 2023. Embracing change in tandem: resilience and sustainability together transforming supply chains. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 43(1), pp.166-196.

Visser, W. and Kymal, C., 2015. Integrated value creation (IVC): beyond corporate social responsibility (CSR) and creating shared value (CSV). Journal of International Business Ethics, 8(1), pp.29-43.

Yasir Hayat Mughal, Kesavan Sreekantan Nair, Arif, M., Fahad Albejaidi, Thurasamy Ramayah, Muhammad Asif Chuadhry and Saqib Yaqoob Malik (2023). Employees’ Perceptions of Green Supply-Chain Management, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Sustainability in Organizations: Mediating Effect of Reflective Moral Attentiveness. Sustainability, 15(13), pp.10528–10528. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310528.

Yu, D. and Zhao, P., 2022. Global Value Chain Governance of the Apparel Design Industry under the Background of Global Sustainable Economic Development. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2022.

Zavala-Alcívar, A., Verdecho, M.-J. and Alfaro-Saiz, J.-J. (2020). A Conceptual Framework to Manage Resilience and Increase Sustainability in the Supply Chain. Sustainability, 12(16), p.6300. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166300.

Appendix

Appendix A: Chart of Goals

The charts display a double-edged challenge: on the one hand, reconciling short-term financial objectives focused on the immediacy of profitability and quarterly targets with long-term sustainability objectives that contain environmental and social considerations. Both are essential, but the alignment is hard to obtain due to the investors’ pressure from the short term and the up-front cost of the sustainability initiatives. Management needs value communication of sustainability, a long-term thinking culture, and innovative attempts to align the financial and sustainability goals. In integrating such strategies, organisations can deal with the tension between short-term financial demands and long-term sustainability imperatives to ensure enduring success in today’s business environment.

Appendix B: Chart on the impact of globalisation on supplier selection Practices

The Above bar chart shows the changing influences of globalisation over supplier selection practices, reflecting key characteristics described in the text. Every bar stands for a facet of global supplier selection, with its height showing relative impact. This is proof enough that a globally connected world has presented a wide array of potential suppliers, with increased interconnectivity and accessibility for its significant impact to be shown. The re-evaluation of criteria for supplier selection reflects a moderate impact in terms of organisations shifting because of location and cultural nuances. Based on the current technological advances, real-time collaboration and knowledge sharing have a lower impact but are growing in importance. The sourcing and collaboration revolution signals a possible major shift in practices, indicative of globalisation’s profound influence on supplier dynamics.

write

write