Abstract:

The Economics of Education outlines is underlined by the frameworks of demand for education, availability of finance, and provision of education, as well as comparative efficiency of educational programs. In this essay, research outlines that based on these established parameters, Chinese students studying in the U.S. as well as the public and private institutions of learning, have an edge or comparative advantages in conducting the trade and offering the students education as the universities gain from the revenues and the students gain from the perceived exposure to the institutions mainly through cultural, economic, and social capitals. However, the continued tug of war between China and the United States is hurting the students since the political platform is contributing to both cultural, social, and economic attacks on the image of Chinese students, effectively contributing to their ostracizing and discrimination, as well as increased policies that are financially damaging to the students. Post-COVID-19, these sentiments have been magnified, leading to an increase in the marginalization of Chinese students.

Introduction

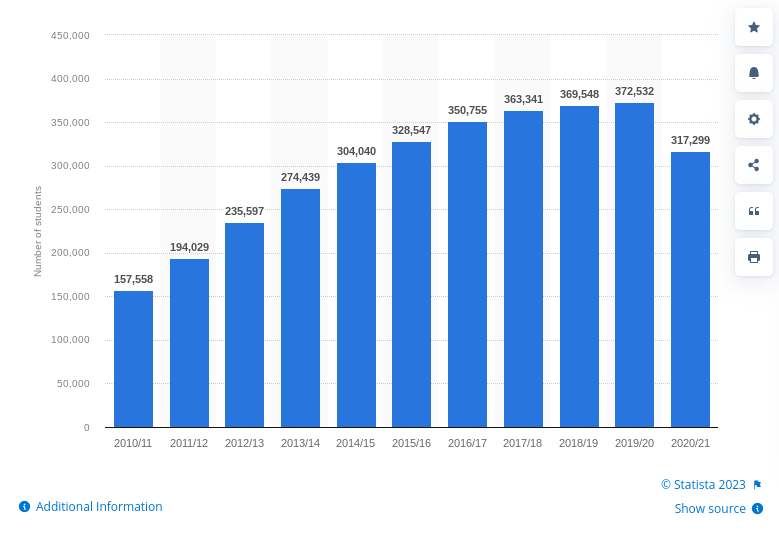

The United States and China currently have mutual political, economic, and security interests that underline their general relationship in the global arena. These mutual areas of cooperation, in consideration of their economic sizes, have been beneficial in both foreign investment, trade, and geopolitics in the increasingly globalized system. One of the many arenas where their cooperation is heavily reflected is in education, where a large majority of Chinese students usually apply to study in both public and private American institutions, and in return, these universities get to earn much-needed revenue to fund their activities. Research indicates that in total international students that came to the U.S. for higher education have been of significant economic impact on the United States as they contributed up to $39.4 billion to the U.S. economy in 2016/17, and the Number that was in the rise ever since (Chao, 2018). The rise in acceptance of international students is a situation that has been propelled by a lack of adequate funding for local public universities in the U.S., partly due to a lack of adequate domestic students, a decrease in corporate support for universities, and declined government subsidies (Chao, 2018). As of 2019, prior to the development of the Covid-19 pandemic, the total contribution of over 1,075,496 international students in the U.S. stood at around $44 billion, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce (Zhang, 2021). Of these figures, 35% of all international students were from mainland China, effectively defining the Chinese international student population as the single largest population of international students in the U.S. (Zhang, 2021).

[Number of college and university students from China in the United States from the academic year 2010/11 to 2020/21- Statista]

While Covid-19 has played a significant role in temporarily halting the numbers, researchers reveal that the wave of studying abroad by Chinese students has not halted partly since the movement is socio-culturally motivated by a need for students to gain international exposure and a worldview education that is more open and less constrained than their locally provided courses back in China (Zhang, 2021). Back home in China, this perspective is also being considered by the government, which seeks to create a more inclusive world-perspective educational curriculum that will open more doors for Chinese academics to compete in an increasingly globalized world. Chao (2018) outlines that “Chinese institutions are also under pressure from the government to offer academic programs that facilitate an easier way to employment, other English-speaking countries also offer education in English and at a lower cost in tuition and fees than many U.S. institutions.” Effectively, the economic theory of comparative advantage comes to play heavily in how many Chinese foreign students make their decisions to study abroad, especially in countries such as Canada, the U.S., the U.K., and Australia, and this same theory has come to interplay Chinese and American foreign relations in almost all spheres.

Background and Theoretical Framework

The theory of comparative advantage outlines that an economy has a comparative advantage when it has the ability to produce a particular good or service at a lower opportunity cost than its trading partner. Opportunity cost is introduced as a factor for analysis in choosing between the different options for the production of goods or services or in the acquisition of services (Costinot, 2009). Under the globalized system, the Westernized education system has always been hailed as a leader in global rankings due to its ability to easily provide its students with employment in their home countries, superior access to resources and tools of learning, easy access to a wide range of collaborative spaces, as well as ease in access for funding and help in research (English, Allison, & Ma, 2016). This has often seen many people in China view the Western education system as superior compared to the Chinese, and the fact that dozens of students from other regions in the world hold this perception has only worked to reinstate the position of the Western schooling system as superior (Zhang, 2021). While for most of history, this was true partly due to colonialism and imperialism that systemically saw the global south unilaterally undermined by the global north, in the late 20th and 21st centuries, waves of investment in some countries in the global south have been changing this perspective and even in some cases reversing the wave (English, Allison & Ma, 2016). This is, however, not the case in China.

The rapid economic development and increase in the need for human resources in China have resulted in a rise in demand for qualified students. Zhang (2021) outlines that within Chinese society, despite the shift from hard power to soft power in regard to culture, educational attainment is highly prioritized and remains authoritarian in nature. As such, parents pressure their kids to work hard in order to join the most prestigious universities and, in so doing, charter a great future for themselves. However, many are dissatisfied with the traditional Chinese education model that places so much authoritarian emphasis on students’ need to succeed academically (Chao, 2016). Research as such indicates that the “growing middle-class Chinese families can afford to support their children’s overseas studies. They send them abroad for a variety of reasons, including to reduce the pressure of China’s standardized tests and the increasing privatization of Chinese education.” Here Zhang outlines that the high-stakes Gaokao exams (University entrance exams in China) place so much pressure on students as they define what universities they will join and, in a way, charter their future jobs and social relations. For many of the middle and upper-class families that have access to resources, an education abroad, especially for their children who did not succeed in gaining admission into prestigious Chinese universities, becomes an option. The comparative advantage here is that the “Chinese society believes that the U.S. higher education system has the value to embrace creativity and diversity. Thus, Chinese international students are critical for U.S. higher education institutions as they bring significant economic benefits and transnational diversity” (Zhang, 2021). This, as such, creates a need for more students to study abroad.

Relationship Between The U.S. and China

Generally speaking, from a Chinese ideological perspective, the failures in the neoclassical economic model that is widely heralded by the West have been key in contributing to the rise of parallel global governance and the struggle for global power that is seen to undermine the relationship between the U.S. and China. The West has been at the forefront of economic and social development across the world, thanks to its liberal policies ushered by democracy (Stiglitz, 2010). Liberal policies are important as they have allowed the West to define itself as separate from other nations first and allowed them to achieve growth and leveraged dominance of other societies; then create bilateral engagements between countries of the world that have worked in boosting social development, economic development and political transparency for growth and stability (Cowen, 2011). Why is all these important in the topic of parallel global governance and the relationship between the U.S. and China? China, for the most part of the late 20th century and early 21st century, has been the single greatest beneficiary of globalization (Henderson, Appelbaum & Ho, 2013). Within the sub-topic of globalization lies an important emerging aspect that can be summarily contextualized as the globalization of politics and political systems; that all together are symbolized by a nation, kingdom, or state’s economic superiority, country’s drivenness, and country-specific culture domination. These aspects allow an individual country to define its position within the global environment (Pieterse, 2010). It also allows the country to outline its future position, which works well in defining its well-being and using its power to develop itself and, in the process, also give its partner nations development and growth.

Parallel governance, a phenomenon gained through globalization, has manifested in institutional multiplicity over claims to governance that promote other actors separate from the “traditional” Western state institutions and interest policies to participate in the facilitation of services for economic, social, cultural, and political development across the world. This is akin to implying that globalization has played a central role in the creation of a new world order. As such, globalization can be regarded as a major disruptor of the world economic order. This is the earliest stage of the global governance shift from the West to the East (China). As such, in the West, many may argue that China is trying to redefine the international economic systems for its benefit at the expense of the West, and herein lies the problem between the West (particularly U.S.) and China. Effectively, the rise of China has ushered in the sense of parallel governance of global economic systems disrupting trade balances between nations, and in so doing, this has become a major interruption to the traditional system of governance that defined growth and the relationship between developed and the developing world in regard to policy formation; creating greater rifts between China and the U.S. but all the same working to achieve change within the world’s governance. At the center of this debate are the Chinese students who have come to the U.S. for education, and them being large revenue streams become both a playing card for China and U.S. Global relations.

Generally, the relationship between China and the U.S. has been deteriorating for a number of reasons, and at the center of it have been poor trade and economic policies to contain each country’s national interest abroad. For most of the period prior to the formulation of the United Nations General Assembly of Nations, the West played a critical role in defining the world economic system. It self-assigned greater privileges to countries of the world based on racial identity. Eurocentric countries were favored the most. This was followed by Asiatic, Middle-Eastern, and, finally, African countries that got precedence, favored treatment, and hindered growth with limited access to the international market purely based on biases hinged on (but not limited to) racial superiority. Aspects such as imperialism, racial segregation, and colonization are important attributes of this perspective. They were necessary for situating Western global governance at a central role, which in turn, wiped out indigenous cultures. They also worked in defining the importance of the neoclassical model as they allowed the West to favor one race within their economic system above other equally deserving one. In fact, the May Fourth Movement (1919), a critical turning point for China’s economic development, was an uprising against blatant Western racism after the first world war, when the West sought to assign European powers to control over China, a critical ally in the allied defeat of the axis powers. Nonetheless, this essay does not seek to dwell on that. On the contrary, it dwells on defining the Western marketplace, identifying that the neoclassical model enabled early Western domination and its perceived “superiority” supporting capitalism in the absence of equality, in turn, created globalization working to aid China’s ascension to power over the West.

An inherent lack of equality stemming from non-inclusive political and economic space promoted a skewed model of capitalism that favored the rich and the majority white population over the minority. This creates governance problems and works to hinder sustained development as it promotes aspects such as imbalanced political systems, migration, etc. Panster (2014.) identifies with this line of thought, stating that “Contemporary global capitalism with its flexible production and accumulation systems and facilitated by new information and communication technologies come with negative externalities such as deep financial instability, joblessness, environmental degradation, violence, ethnic conflict and tensions between the state and the market” (p2). All these factors cumulatively play a role in the implementation of economic policies and, in turn, create turbulent economic growth in the era of equality as they expose the weakness in neoclassical models that only favored one racial group over others equally deserving. They, in turn, allowed the West to slowly lose its grip of domination of the economic outlook to China, whose government has more firm control over the market and humans.

After the promulgation of a more inclusive international economic system, most of the West continued to passively approach their systemic failure on issues such as racism, discrimination, genderism, etc. The effects, in turn, as Panster (2014.) identifies, is that “the global transition to neo-liberal post-Fordism has exacerbated existing inequalities and created new ones… [there is] persistent unequal distribution of opportunities, wealth and risks among regions, countries, groups, and individuals” (p2). This constant systemic failure was not only maintained within the U.S. and other Western states but exported to other regions of the world, creating different perspectives that were key in defining their country-drivenness to defining themselves and their values separate from the West, experimenting on a variety of models in a bid to achieve economic success.

Block policy formation on many important issues that define the political and economic well-being of other countries continues to shape how the world approaches interdependency between various established and rising economic systems. It also dictates the power of various important Western-led institutions, such as the world bank, in influencing trading patterns between countries. Globalization is a key aspect that has managed to sustain the rise and domination of multinational corporations. In the case of China, its rise is effectively an international spectacle where multinationals from other regions invested heavily within its system, boosting its infrastructure, creating jobs that took people out of poverty, and paying taxes while still maintaining a level of independence and separation from China. This was critical in allowing China to sustain its own economy and define its own image separately from the West but still harbor Western ideals.

While the Western MNCs (multinational corporations) still maintained a level of predominance over their individual operation, the Chinese government benefited from the sheer size of the Number of multinational corporations seeking to establish themselves within China. There are two things that need to be understood in how the West’s neoclassical model continuously serves to bring about Chinese domination. Arguably, the neoclassical model hindered Western nations from truly interacting with the Chinese system of governance rather than treating them separately. This resulted in them maintaining mutual separation since they perceived China as an outsider and a threat to their domination. As such only dwelled in manufacturing and exploitation of the population but in a manner that they gave back in employment. This works in depriving their own people back in the West of lucrative manufacturing jobs since it is cheaper to produce in China. Secondly, Chhachhi (2014) identifies that “Neoliberal globalization, the hypermobility of capital, has led to the emergence of new forms of flexible work/ labor, the co-existence of old and new working classes…realigning class structures nationally and globally” (p895). Cumulatively these two factors have worked in defining China as the new emerging global power, a title it had lost at the dawn of the industrialization era.

When the figurative low-hanging fruit was snatched away from China, which enjoyed dominance through sheer population size, to the West through greater technology, free labor, free land, and global domination that came with technological innovation, the aforementioned factor where liberalization started equalizing the playing field contributed in creating an aspect of influence diffusion. Additionally, it has worked to oversee the making of Western “traditional” systems less dependable for other Western nations and, more importantly, developing nations that now have relatively more influence economically, like China which has, in turn, led to the rising tension between the United States and China, that is spilling over to all sectors of mutual cooperation.

Market Influence: Comparative Advantage Economics

Relative to comparative advantage economics, the function of economics of education is to evaluate the underlying issues relating to educational attainment and includes the demand for education, the financing, and provision of education, the comparative efficiency of the education programs as well as policies implemented. The theory of comparative advantage generally focuses on economic factors that define access to a product or service, but in this case, the relationship between the United States and China goes beyond economic association and also includes cultural experiences. Cultural experiences will also be applied to understand how it affects Chinese international students (who will also be referred to as Chinese Students) when applying to American universities, implying mutual benefit to China and U.S. universities. As already established by Zhang, the majority of the students who apply to join schools in the U.S. do so by paying full tuition from their own parent’s pockets. This is to imply that they are failure economically independent. Chao (2016) additionally outlines that for international students studying in private or public universities, the amount they pay is fairly higher than their American counterparts. Research outlines that “In many countries,..In about half of the OECD countries, public educational institutions charge different tuition fees for national and foreign students enrolled in the same programs … In absolute levels, the difference in tuition fees between national and foreign stu-dents can be very large: in all the aforementioned countries (except Austria), this difference exceeds US$8,000 per year” (Sanchez-Serra & Marconi, 2018). While it is undeniable that these extreme amounts can be very constraining for parents, for the most part, it is part of the official policy to avoid politicizing the high Number of foreign students within a country. But this can work effectively when the foreign population is significantly lower than in cases where the Number of foreign students is in the hundreds of thousands. Here comparative advantage economics as such can be perceived to be in favor of both U.S. (from a cultural perspective) and China (from an economic perspective) as the U.S. provides the infrastructure and cultural frameworks for studying, and in return, China provides the much-needed money/ revenue for U.S. institutions that need the money. On the contrary, the war limits the comparative advantage principle that was set by the earlier agreements between the countries (Kone, 2019). Based on the framework established (demand for education, availability of finance and provision of education, as well as comparative efficiency of educational programs), there are numerous comparative advantages that Chinese students gain from studying abroad, as opposed to studying at home that can be effective in understanding how the relationship between the U.S. and China may come to impact their rates of application.

High Demand for Education in China

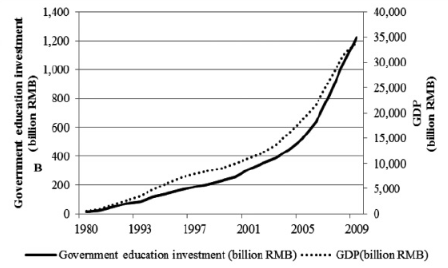

Generally, with the high economic growth being registered in China, more and more parents are eager for their children to gain an education so that they can be able to become part of the workforce that is emerging in China. In the context of mainland China alone, the Chinese government is rapidly revolutionizing the education system to entice more students to study at home. Juani (2017) outlines a framework of the push-pull model which establishes why more and more students decide to study abroad; international students’ mobility to study abroad was compelled by the lack of favorable conditions to access education in their home countries, as well as the availability of advanced opportunities and facilities in host countries. Zhang (2021) identified that this, along with the high competition that is seen in the Gaokao exams, tends to push more and more people to consider options abroad. Jiani (2017) also identified access to scholarships abroad, which led to a rise in applicants from China. However, the government of China, in fear of brain drain, has invested heavily in broadening the Chinese educational system and effectively increased the licenses provided to both public and private schools. Chow & Shen (2006) outline that between 1991-2002, quantitative changes in education spending by the framework of demand analysis and explained under the income and price effects showed that middle and upper-class parents were spending more on tuition fees for their children both in China and abroad, while the government was investing more to ensure the gap on education inequality and education opportunities were being closed.

[Chinese Government Spending on Education from 1980 to 2009]

Additionally, Jiani showed the availability and access to scholarship opportunities abroad led to many international students deciding to go to countries in the OECD based on government promises to offer scholarships. The country’s economic ranking and level of as well as the future prospect of working out of China and the bright prospect of from a worldview were all push factors under the level of country selection (Jiani, 2017). Based on the individual level, the three motivation factors based on US/ OECD country selection include; the need to promote career development and explore a new way of life by experiencing a different culture.

Many factors influence the decision-making process of Chinese overseas students. Effectively, career decision-making, thematic cultural environment analysis, social cognitive career theory, and the general perception that the study abroad experience is better to underline why more students choose not to study in China. Wu (2020) outlines the three main factors that shaped Chinese overseas students’ career decisions: family influences, better perception of overseas social life, and personal improvement. The study’s conclusions show that family influences are vital in a Chinese student choosing a career because it is essential that the profession chosen by the individual honors the family and fulfills the family’s expectations. As for overseas social life, many students find these prospects a crucial factor since it involves the individual deciding if they will be able to fit into their new environment. Wu (2020) outlines this to include the prospects of a “new culture and lifestyle while studying to produce high-quality work .”Personal improvement comes in when individuals want to find better career opportunities to better their lives. The publication relates to other literature in the field by adding to the already established knowledge of the factors influencing Chinese students’ career decision-making process.

Comparative Efficiency of the Educational Program

The demand for international higher education, especially in China, keeps increasing based on the significant increase in the Number of self-funded overseas students (Wu, 2014). Results of empirical research of Chinese students in Britain outlined some of the motivating factors for pursuing postgraduate programs abroad, including the normal cultural enrichment and access to avenues of personal growth in the context of a globalized world, but most importantly, it included sentiments that Britain had a high-quality program and length of and access to postgraduate programs was much more liberal (Wu, 2014). In line with this, a separate study that evaluated the likelihood of Chinese students to go study abroad outlined a good policy regime that promotes access to education for specific students. Bamber (2014) outlines that a key driver for many Chinese female STEM students’ uptake of U.K. studies was underlined by the relationship between China and the U.K. concerning providing Master level programs, especially for Chinese Women. The study results show that prior studies attracted Asian students to study based on their academic expectations and aspirations. Chinese women clearly stated that their qualification would hopefully support their early mid-career changes, which would not be achievable by just having an undergraduate degree from an institution at their home (Bamber, 2014). A more precise argument provided is that the majority of the students who studied abroad showed an increase in intercultural communication competence than those who did not. This level of skills becomes important in evaluating the efficiency of education, considering research indicates that most students want to study abroad so that they can fit into the global market. William (2005) outlines that most U.S. universities concentrate on key concepts of studies such as intercultural communications, cross-cultural adaptability, and cross-cultural sensitivity owing to a larger number of diverse populations. William’s empirical research conducted interviews on the impacts of intercultural communication skills, viewing the subject in a variety of dimensions: emotional resilience, perceptual acuity, personal autonomy, flexibility, and openness. The study outlined that students who studied abroad showed a greater increase in intercultural communication skills than the students that did not study abroad (Williams, 2005). The results showed that the better predictor of intercultural communication skills was exposure to various cultures compared to location.

However, the effectiveness of education was called into question in other research as some of the studies revealed that, in some instances, some students scored far less abroad than their local counterparts owing to cultural shocks. Fang & Wei (2016) addresses the fine line between success and failure for Chinese students who study abroad in the Master in Education program. The key concepts they cover in their research include the variety of Chinese students’ program evaluation procedures and the internalization of higher education frameworks differently in China as opposed to the U.S. The results of this study involved four emergent themes that were in response to the survey in progress about students’ abroad experiences. The themes included; the reluctant speaker, a comparison problem, the informal and hidden curricula, and finally, the engagement with the difference (Fang & Wei, 2016). The majority of the students who failed to acclimatize to the new cultural value system were heavily impacted by the new curriculum and culture, which ultimately undermined their ability to study effectively.

Evaluation of How A Poor Relation Between China and The U.S. Effect The Chinese Chinese Student Applicants in U.S. Public and Private Universities

Based on the above results, it is clear to see that the Chinese student’s decision to study abroad comes with a lot of comparative advantages for them, as well as their respective public and private institutions. The institutions gain a lot from the money they bring, while the Chinese students gain much-needed exposure to a different worldview, they gain access to global knowledge that as such informs them on the prevailing market conditions and career paths, and most importantly, they gain significantly through proper research and educational tool, that they might have never accessed due to either a poorly funded/ constrained Chinese education system that is also highly competitive. How, then, does the poor relationship between the U.S. and China affect their application rates?

The general guiding force for most societies is that a social contract exists between the people (general polity) and those they choose to rule them. Simmons and Lawrence (2001) specify that the Social Contract Theory precludes humanity as a force of organization without rules, but people intentionally create and enforce rules to allow for social development. As such, power is bestowed on a few to help organize the rest and prevent the general society from descending to chaos. When the rules of law fail to be exercised accordingly, limited actors within the society gain power, and how they use this power will determine how other factors central to the communities organization become enforced and viewed. How is this important? Political offices in both the U.S. and China have great power. Observing how they apply their power has become a great position to understand how discourse has been framed. There are various tools used to frame the discourse in both China and the U.S. They include:

- The media

- Political actors (representing vested interest subjective to economic entities rather than the citizenry)

- Think Tanks, Lobbyist, and political & Economic advisors

- Individual traders

- Consumer and consumer trends.

The ability to recognize the problem and project a subjective view to the rest of the people summarily becomes a means of framing a problem. McLuhan & Quentin (1967) identifies that the medium has become the message rather than the message itself. This is to imply that the ability to project a message lies in the person that controls the medium, as they have the power to shape the message. As such, controlling the media becomes as important as shaping the message itself. The media that is politically controlled takes center stage in perceiving either country’s actions as negative or positive in line with the country’s economic interest. It is important that the media’s role has never to specifically support either side but essentially allow the owner of the problem in the construction arena to justify the problems as it affects them. Simmons and Lawrence (2001) argue that the construction of a problem in the West has always been beneficial to the problem’s owner rather than the actual reality of the problem.

As such, the person who brings agency to a problem by shaping it in a certain manner becomes the one who defines how the problem will be solved. The above concept is important in the US-China trade war. Trump, defining China as a country that “RAPES” America, essentially was able to present the problem to the polity as one of an unjust country that takes advantage of America and needs to be tamed. His actions evaded the fact that there were millions of Americans who benefited from trade with China, escalating the conflict to levels where they could not present their claims as Trump’s claim superseded theirs in the eyes of the nation. For many Chinese students in America, the negative relations between China and the U.S. are flaring up both hate crimes and official designation, leading to institutions targeting Chinese students in manners that effectively harm their prospects of studying abroad. This has seen universities in the U.S. take up policies that seek to undermine direct admission and push Chinese students to study online, which is counter to the positions they seek (Ching et al., 2017). On the contrary, it has pushed the Chinese government to invest heavily in education in order to prevent the increasing brain drain being recorded at the moment and the high chances of intellectual property rights loss for Chinese students in U.S. institutions (Hai, Dutton & Cohen, 2022). Effectively for most Chinese students, the prospects of their education abroad, while at the moment fairly legal, seem to be undergoing huge changes, with both governments working against it for the benefit of their personal interest.

Conclusion

Conclusively the biggest loser in this fight between the biggest economies in the world will be the students. Chinese Students who have contributed significantly to the U.S. educational system by providing critical revenues for university campuses, both public and private, are increasingly being used as pawns in a system of global geopolitics that seeks to cater to individual countries’ self-interest. These interests are pegged on global governance and global domination relative to the policies of trade, economy, military, and culture. Both higher learning institutions and the individual international student have a comparative advantage in getting to learn in these institutions, but the failure of their government to create a conducive environment for both is resulting in higher educational costs, poor acculturation, and a general lack of avenues for more students to gain access to opportunities for studying abroad.

References

Bamber, M. (2014). What motivates Chinese women to study in the U.K., and how do they perceive their experience? Higher Education, 68(1), 47+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A373677980/AONE?u=miami_richter&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=fa2dd59c

Chao, C. (2018). Why do so Many Chinese Students Come to the U.S. for their Higher

Chhachhi. (2014). Introduction: The ‘Labour Question’ in Contemporary Capitalism. In Development and Change. 45: pp. 895–919.

Costinot, A. (2009). An Elementary Theory of Comparative Advantage. Econometrica, 77(4), 1165–1192. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40263857

Cowen, T. (2011). The Low-Hanging Fruit. In The Great Stagnation: How America ate all the low-hanging fruit of modern history, got sick, and Will (Eventually) feel better: A penguin, especially from Dutton. Penguin.

Education? Asian Journal of Education and e-Learning, 6(3). DOI:10.24203/ajeel.v6i3.5306

English, A. S., Allison, J., & Ma, J. H. (2016). Understanding Western students: Motivations and benefits for studying in China. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 4(8). https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v4i8.1499

Experiences in the United States. Institutional Repository (I.R.) at the University of San Francisco (USF), hosted by Gleeson Library. https://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1588&context=diss

Fang, Clarke, A., & Wei, Y. (2016). Empty Success or Brilliant Failure. Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(2), 140–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315315587106

Hai, H. (., Dutton, P. A., & Cohen, J. A. (2022). Chinese attitudes toward intellectual property

Henderson, J., Appelbaum, R. P., & Ho, S. Y. (2013). Globalization with Chinese characteristics: Externalization, dynamics, and transformations. Development and Change, 44(6), 1221–1253. doi:10.1111/dech.12066

International students studying in the United States. Educational Research and Reviews, 12(8), 473–482. DOI:10.5897/ERR2016.3106

Jiani, M. A. (2017). Why and how international students choose Mainland China as a higher education study abroad destination. Higher Education, 74(4), 563+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A503527164/AONE?u=miami_richter&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=8fe3df82

Kone, S. (2019). USA–China trade war in light of the limits of the comparative advantage

McLuhan, Marshall, and Quentin Fiore. The Medium Is the Massage. New York, London,

Panster, W. G. (2014). Inequality, pluralism, and the environment: Global Context and Conceptual Debates. In Opening Up Conceptual Pathways.

Pieterse, J. N. (2010). Future of Development. In Development theory. SAGE Publications.

Police brutality. Contemporary Sociology, 30(5), 520.Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.2307/3089363

Principle. Management and Economics Research Journal, 5, 1. https://doi.org/10.18639/merj.2019.961704

Rights change and continuity. American Journal of Trade and Policy, 9(2), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.18034/ajtp.v9i2.621

Sanchez-Serra, D., & Marconi, G. (2018). Increasing International Students’ Tuition Fees: The

Simmons, H. P., & Lawrence, R. G. (2001). The politics of force: Media and the construction of

Stiglitz, J. E. (2010). Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. Toronto: Bantam Books, 1967. Print.

Two Sides of the Coin. International Higher Education, (92), 13-14.

Williams, T. R. (2005). Exploring the Impact of Study Abroad on Students’ Intercultural Communication Skills: Adaptability and Sensitivity. Journal of Studies in International Education, 9(4), 356–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315305277681

Wu, Y (2020) Study Abroad Experience and Career Decision-Making: A Qualitative Study of Chinese Students. Frontiers of Education in China 15(2):313-331 DOI:10.1007/s11516-020-0014-8

Wu. (2014). Motivations and Decision-Making Processes of Mainland Chinese Students for Undertaking Master’s Programs Abroad. Journal of Studies in International Education, 18(5), 426–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315313519823

Yuerong, C., Renes, S., Samantha, M., & Joni, S. (2017). Challenges facing Chinese

Zhang, S. (2021). Voices of Chinese International Students

write

write