Abstract

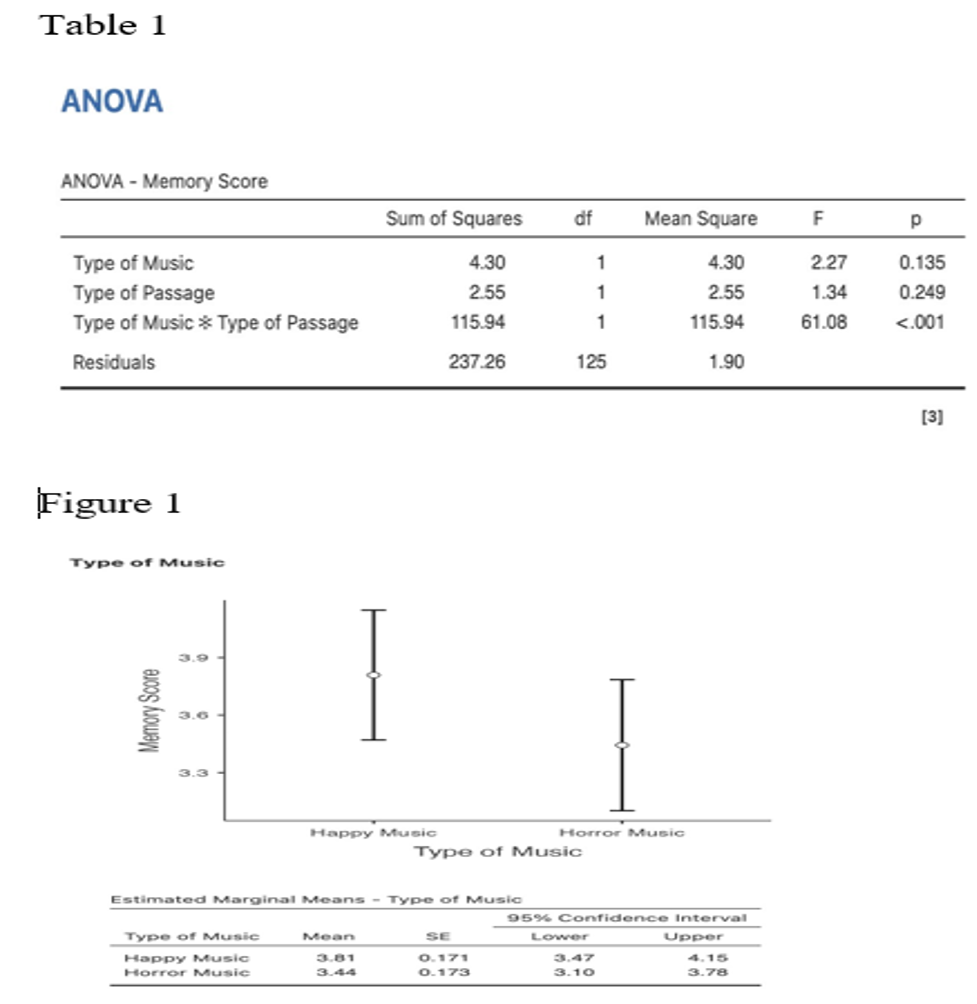

In cognitive research, the study of how the type of music and the type of reading materials interact and influence memory and retention is compelling. Recent studies have emphasized the significance of this interaction by showing how the emotional tone of background music and reading material affects learning outcomes and memory retention. This research investigates how matching or mismatching music’s emotional tones (happy or horror-themed) and reading passages (happy or horror-themed) affect memory retention. The number of total participants for this study was 128 (N=128). The study adopted an experimental design and utilized Google Forms for its survey. A 2×2 between subjects factorial ANOVA design was conducted to examine the main effect of the type of music on Memory Retention, the main effect of the Type of passage on Memory retention, and the interaction between the type of music and the type of the type of passage on Memory retention. The study did not show any significant main effect on memory based on the type of music F(1, 125)= 2.27 p =0.135. Also, there was no difference between happy music (M = 3.85) and horror music (M = 3.38).

Introduction (Background and Rationale)

Memory retention refers to the ability of the brain to remember or retrieve information that has been stored in long-term memory over a period of time. Essentially, memory is the continued retention of information over time. In particular, the impact of music on cognition has been subjected to various studies which have had differing findings. A study by Smith (1985) explored the impact of background sound in inducing context-dependent memory and established that the context-dependent memory that is caused by contextual sound tends to be the advantageous result of contextual signaling instead of the deleterious effects that can be caused by distractions of the background. Smith (1985) pointed out that variations of the background contexts in which events occur affect memory in ways that the memory is determined by the relation between the contexts of test and learning. Context-dependent memory (CDM) can be affected by contexts such as the physical environment, mood states, posture, speaker voice, background colors, and meaningful verbal materials. This article is relevant to this study through its approach to examining how the context of the music, or the music itself and thus the reading material, can affect memory and retention.

Also, a study by Ferreri and Verga (2016) explored the benefits of music on verbal learning and memory. As such, the study established that the ability of music to boost cognition has also been associated with the verbal stimuli employed and the complexity of the music (Ferreri and Verga, 2016). Ferreri and Verga’s article is of great relevance to this study as it seeks to explore the various ways through which cognition can be affected by various components of music, including the complexities and the verbal stimuli that the music employs. Essentially, the study points out that the listening experience of a song can significantly affect memory and cognition. Understanding the various aspects of music and learning materials that affect memory and cognition adds to the knowledge about the ways and approaches that, when used, can enhance cognition in individuals. `

This research investigates how matching or mismatching the emotional tones of music (either happy or horror-themed) and reading passages (happy or horror-themed) affects memory retention. The study will seek to establish whether the kind of music that a person listens to and the reading materials or passages that they interact with will have impacts on their memory and retention. The hypothesis suggests that congruent emotional tones between music and reading material will lead to improved memory retention, and the study also considers how demographic factors may play a role in these effects. As such, the study hypothesizes that happy music leads to better retention, while horror stories will result in better retention. Participants listening to horror music will have a higher percentage of recall when reading a horror passage compared to a happy passage. These hypotheses align with the study’s main goal of examining how the type of music and reading material can affect memory and retention. The identified hypotheses will act as guidance throughout the study with the aim of establishing whether they are true or not. By covering this, the study will have established the effects of the genre of music and the type of reading on memory and retention, establishing ways through which memory and retention can be enhanced.

Methods

Participants

The number of total participants for this study was 128 (N=128). The participants were sourced from the social circles of the research team. The eligibility criteria for inclusion in the study were based on age factors, whereby the participants had to be over 18 years old. The participants were recruited through social media platforms, including Instagram and WhatsApp. Word of mouth through the research team was also used as a means of recruitment. Among those recruited, 56.3% were female and 43.8% male. In terms of race, 38.3% were White, and 95.4% ranged between 18 and 28 years of age. Blacks made up 11.7% of the recruited participants. Thirty-two of the recruited participants were placed in one of the four treatment conditions.

Materials

For the purpose of a survey, Google Forms, which were administered by the team members to participants upon contact, were used. The participants then completed the surveys on their own devices. There were four groups in the study, and each participant was assigned to one of the groups. The participants began the survey with a consent page, which was then followed by questions from a mood state questionnaire. The entire study ensured that standardized backgrounds and text colors were used. Throughout the study, the participants believed that they were completing an experiment on how music affects mood.

Procedure

The study adopted an experimental design. The study had two independent variables, which had two levels. Independent variable 1 was the type of music whose levels were horror and happy music. Independent variable 2 was the type of passage. The dependent variable for the study was memory retention, which was measured by the correct number of questions answered by the participants. Participants were assigned questionnaires for surveys that needed them to complete informed consent to ensure the study aligned with ethical considerations. The mood questionnaires were then administered, with the participants also supposed to give a one-sentence task descriptor. A 2×2 factorial design was utilized to randomly assign the participants to one of the four conditions. The participants were then assigned music to listen to and passages to read and, thereafter, responded to structured questionnaires. The researchers imposed rigorous control measures that sought to ensure consistent exposure times for music and reading across conditions. For a standardized and effective data collection process, the study implemented digital collection through Google Forms.

Results

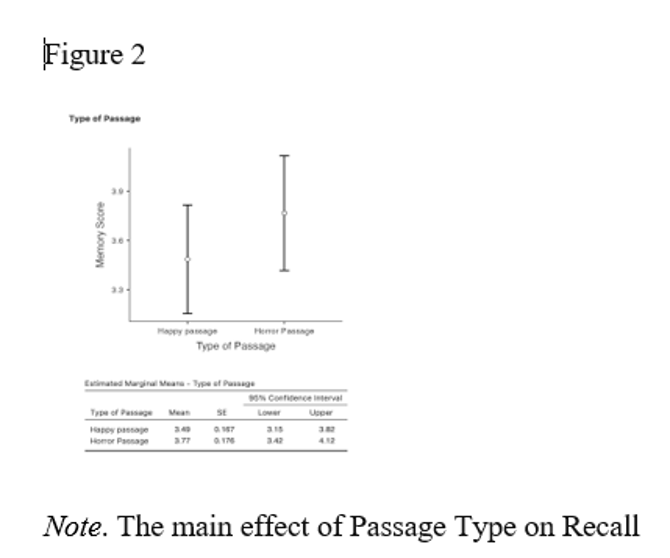

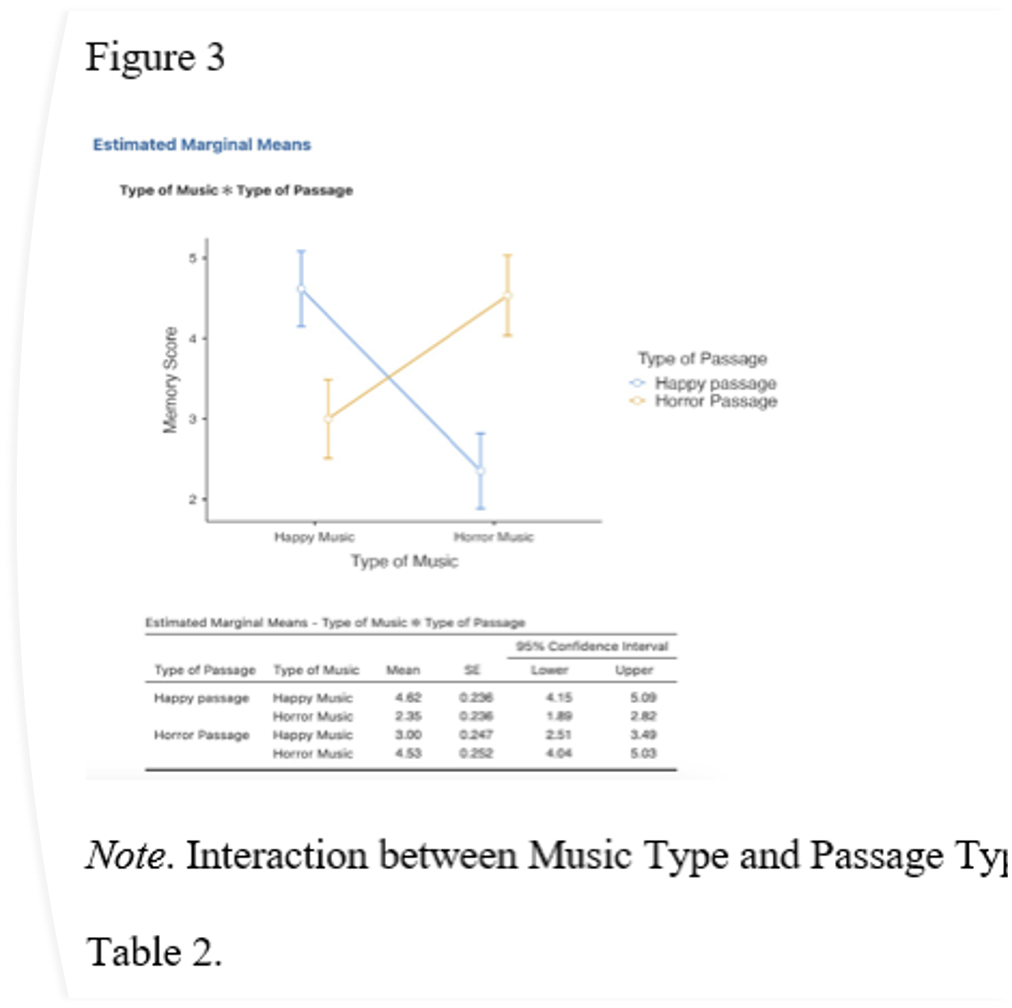

A 2×2 between subjects factorial ANOVA design was conducted to examine the main effect of the type of music on Memory Retention, the main effect of the Type of passage on Memory retention, and to examine the interaction between the type of music and the type of the type of passage on Memory retention. The study did not show any significant main effect on memory based on the type of music F(1, 125)= 2.27 p =0.135. Also, there was no difference between happy music (M = 3.85) and horror music (M = 3.38). Similarly, there was no significant effect of the type of passage on memory recall F(1, 125)= F 1.38, p =0.249. There was no difference between Happy passage (M = 3.49) and Horror music (M = 3.75). In the third variable, there was a significant interaction between type of music and type of passage on memory recall, F(1, 125)= 61.8, p = <.001. Post-hoc comparisons using a Ptukey post-hoc test indicated that the mean Memory recall for the Happy music and horror passage group was significantly different than the happy music and horror passage group, t(125) = 4.728, p = <.001. The mean memory recall for the happy music group with the happy passage (M =4.62 was higher/ than the happy music group with the horror passage group (M =2.35). Post-hoc comparisons using a Ptukey post-hoc test indicated that the mean Memory recall for the Happy music and happy passage group was significantly different between the horror music happy passage, t(125) = 6.778, p = <.001. Also. The mean memory recall for the happy music group with the happy passage (M =4.62 was higher/ than the horror music group with the happy passage group (M =2.35). Post-hoc comparisons using a Ptukey post-hoc test indicated that the mean Memory recall for the Happy music group was significantly different between the happy passage group and the Horror passage, t (125) = 4.728, p = <.001. The mean memory recall for the happy music group with the happy passage (M =4.62 was higher than the happy music group with the horror passage group (M =2.35). The mean memory recall for the happy music group with the horror passage (M =2.35 was lower/ than the horror music group with the horror passage group (M =4.53).

Discussion

The type of music and passage does not have any impact on memory and recall as there were no differences between happy music, horror music, and passages. However, an interaction between the type of music and the passage on memory recall was significant. As such, congruency between music and passage types significantly improves memory recall. The combination of happy music and a happy passage increases the chances of recall more than when happy music is combined with a horror passage. Essentially, there is an increased recall rate when happy music and happy passages are combined than any other case of variability. Such shows that the type of music and the type of reading materials can significantly affect memory and retention. A happy music and a happy passage increase the chances of recall in an individual, showing the impact of the background and environment on memory and retention. The findings support the arguments and the findings of the studies by Ferreri and Verga (2016) and Smith (1985), who argued that the environment, background sound, the mood of the readers, background colors, and the entire context can influence retention and memory.

Interaction between music and reading can be used as a way of enhancing memory cognition. In most situations, music has been used to assist in language acquisition in learning among impaired children and ameliorate memory loss in demented patients, hence why understanding the effects of music on people can be used to enhance cognitive development (Rickard et al., 2006). Similarly, Benz et al. (2016) noted that there is a positive association between musical training and enhanced cognitive performances, whereby musical experience is associated with benefits in unpracticed tasks and cognitive functions. However, a study by Jancke and Sandman (2010) established that being exposed to different background music of different tempo and consonance have no impact on the learning of verbal material, although there is an event-related synchronization and desynchronization depending on the type of tune (in-tune fast music and out-of-tune fast music) that one is exposed to. Also, Buerger-Cole (2019) failed to establish any relationships between the type of music and psychological processes, underscoring the impact of music on cognitive processes such as recall and memory.

However, the study was not without flaws. One of the most obvious flaws is that the study was subject to recruitment bias, especially since the participants of the study were sourced from the social circles of the research team. The selected participants could have had low recall or recognition levels, and this would give false implications. Abonyi (2003) claimed that although randomized recruitment may be used, it will always result in bias due to its inability to accommodate all groups in a society. Another flaw is the variability between the experimental conditions and the natural world, making the results of the study not reflect real-world conditions or situations. Michaud et al. (2012) supported this flaw in experimental design. They stated that the conditions in which experimental designs are conducted tend to have a significant variation with real-world situations, and this minimizes their applicability in solving real-world problems. This makes the study to not be generalizable. Future studies should consider conducting the experiments in real-world settings to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Also, there is a need for future studies to adopt unbiased recruitment methods over a wide population, as the results would reflect a more diverse society.

Conclusion

This study sought to examine whether the kind of music that a person listens to and the reading materials or passages that they interact with will have an impact on their memory and retention. However, the findings of the study did not establish any impact of the type of music and passage on memory and recall, as there were no differences between happy music, horror music, and passages. However, the findings of the study established that the congruency between music and passage types significantly improves memory recall. However, the study had limitations in that the generalizability of the design used was limited and could not be used to account for real-world situations due to the controlled conditions of the experiment.

Tables and Figures

References

Ferreri, L., & Verga, L. (2016). Benefits of music on verbal learning and memory: How and when does it work? Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 34(2), 167-182. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26417442

Michaud, J. P., Schoenly, K. G., & Moreau, G. (2012). Sampling flies or sampling flaws? Experimental design and inference strength in forensic entomology. Journal of Medical Entomology, 49(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1603/ME10229

Buerger-Cole, H., Agyemang, S., Cotting, G., Joottu, S., & Vetter, K. (2019). How Music Genre Affects Memory Retention & Physiological Indicators of Stress. http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/81993

Smith, S. M. (1985). Background music and context-dependent memory. The American Journal of Psychology, 591-603. https://doi.org/10.2307/1422512

Abonyi, O. S. (2003). Fundamental flaws in experimental research. Journal of Science Teachers Association of Nigeria, 38, 107-111. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Abonyi-Okechukwu/publication/260789892_Fundamental_Flaws_in_Experimental_Research/links/00b7d53239fd6d6e26000000/Fundamental-Flaws-in-Experimental-Research

Benz, S., Sellaro, R., Hommel, B., & Colzato, L. S. (2016). Music makes the world go round: The impact of musical training on non-musical cognitive functions—A review. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02023

Rickard, N. S., Toukhsati, S. R., & Field, S. E. (2005). The effect of music on cognitive performance: Insight from neurobiological and animal studies. Behavioral and cognitive neuroscience reviews, 4(4), 235-261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582305285869

Jäncke, L., & Sandmann, P. (2010). Music listening while you learn: No influence of background music on verbal learning. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 6, 1-14. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1744-9081-6-3

write

write