Introduction

Truancy, usually the frequent act of missing school unauthorized, is a significant problem that negatively impacts the overall effectiveness of educational institutions. Truancy might be defined differently by different municipalities, states, or countries; nevertheless, the most typical and suitable description is a pattern of unjustified absences from the classroom. According to (Kearse-McCastler, 2020), 10 of the most significant issues confronting American schools are related to the tens of thousands of pupils that skip classrooms daily without valid justifications (Aqeel & Rehna, 2020). As a result, absenteeism affects the entire country and substantially negatively impacts the educational system. Approximately 2.4 percent of students worldwide need permission to attend the classroom. One in five learners in New Zealand is classified as truant daily (Cheah, Kee, Lim & Omar, 2021), developing the issue internationally.

According to Keppens & Spruyt (2020), adherence is the most significant variable in determining how well kids perform; hence, early corrective action must be taken against persistent absences. Potential causes of illegal activity must be found to eradicate or at least reduce them. Determine the urgency and significance of the issue to the student’s and society’s health by considering the potential immediate and long-term repercussions of unjustified school absence. Truancy among primary and secondary school students in New Zealand is a growing issue, with more and more students purposefully skipping classes in the face of administrative and classroom management challenges (Fareo, 2019). This issue affects a substantial proportion of pupils in New Zealand and can have long-lasting devastating impacts making it an urgent matter to address (Adubea, 2020).

Methodology

To provide answers to the research questions, research was conducted at a local primary and secondary school, and data was gathered. Also, a broad literature review was conducted from a pool of literature evaluating various research findings of related work from various scholars. The design of “ex-post facto research” was utilized in the present research to examine the link between variables whose manifestations the researcher could not control since they had already taken place (Franknel & Warren, 2000). Understanding the Causes and Determinants of Truancy among Primary and Secondary School Students in New Zealand was made possible by design, which allowed for the collection of qualitative literature review data from reputable academics worldwide.

The study consisted of students, parents, and guardians, with 50 percent of the participants being students from primary school while the remaining from the secondary school sample online participation. The participation gave room to any parent from possible nationalities and age groups ranging from 8 to 15 years, Virtanen et al. (2022). The participants were recruited via emails sent to them and via word of mouth. Participants took part in this study voluntarily with no reward. Demographic data (age, gender) were assessed (Ramberg et al.,2018). All procedures were approved by the university ethics committee that reviewed the research approval documents and the clearance form issued as a go-ahead token for the research. The data study from the concept map focused on various overarching issues related to unauthorized absenteeism in primary and secondary schools, Roth & Erbacher (2021). The incidence of unauthorized absenteeism and the usage of legal justifications reported by students were first analyzed and contrasted with a recorded literature review. Following that, the reasons given by students for engaging in unconstitutional absenteeism were analyzed and categorized into four groups: family-related factors, economic factors, student factors, or school-related variables. Last but not least, responses from educators were analyzed and classified into five groups according to teacher convictions: student success/achievement, repercussions for illegal student absences, reasons for Truancy of students, effects of Truancy of students, and remedies for decreasing or preventing Truancy.

Both the dependent and independent variables were incorporated into the research’s parameters. The family factors, school environment, electronic media, socioeconomic status, peer pressure, cultural determinants, teacher-related, community factors, and economic determinants of student Truancy were among the independent variables, Sorokin (2022). They also included school-associated school determinants, residence-related determinants, and individual-related determinants. The factor that was dependent under inquiry included the impact of Truancy on students’ academic progress in primary and secondary schools.

Results

According to the literature review, 29 percent of primary school students believed in missing educational institutions no more than once per month, twelve percent believed in missing educational institutions once per month, thirty-one percent believed in missing educational institutions at least twice per month, four percent are believed to miss educational institutions once every week, six percent are believed to miss school at least twice per week, and zero percent are believed to miss educational institutions at least four times each week. On the other hand, of secondary schools, Baskerville (2020), 18 percent are believed to have always attended school. In addition, 31 percent of students are believed to have never missed a class, 29 percent are believed to miss a class a maximum of once each month, six percent said they missed a class every month, sixteen percent believed to miss a class at least twice a month, six percent are believed to miss a class at least once a week, eight percent are believed to miss a class at least twice a week, and four percent are believed to miss a class at least four times every week. Furthermore, 44 percent of students are believed to have never handed in a justification for absence from class or educational institutions. Fourteen percent are unsure, and 41 percent are regular absenters, LeClair (2022). The findings mentioned above are supported by the literature review records from various studies, which show that during the 25-week mark of the academic year, there are more than 2000 unauthorized absences from classrooms in the primary and more than 2,500 in the secondary schools.

Furthermore, there have been many permitted absences from the primary and secondary schools. Sadly, for primary and secondary schools, the rate of Truancy is approximately 3.3 times higher compared to the approved absenteeism rate. This supports the argument that unethical absenteeism significantly impairs student progress in the classroom.

Discussion

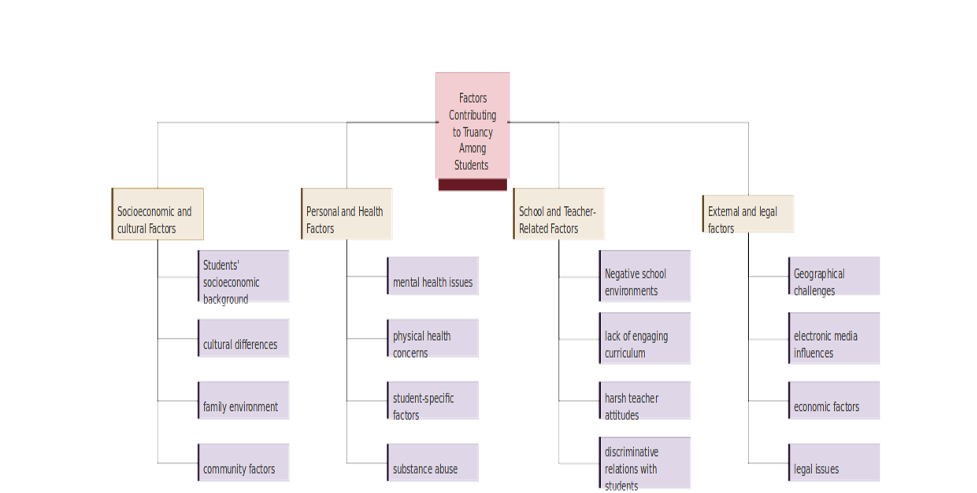

The study outlined various causes of Truancy in school, outlined in the concept map in Figure 1facilitating a broader understanding. The concept map covered the family aspect of after-school supervision for students. According to the literature review, a formal excuse was even less probable to be submitted by 41 percent of students who confessed to failing to attend class at least twice a month, as fifty-eight percent acknowledged not submitting a legal justification (Baskerville, 2019). According to the literature, students who acknowledged missing school two or three times a month or more and acknowledged not providing a valid justification are the leading aspect of low-income family supervision. None of these pupils received supervision right after schooling. About 41 percent of students in primary and secondary always submit an excuse after a truant behavior. According to the findings and connections to the pupil’s health, poor parenting and ignorance can cause mental health problems and a shortage of inspiration to go to school. Also, violence and domestic abuse can cause problems with both mental and physical health, and disputes between families can cause stress and a deficiency of interest in learning.

Figure 1: Factors contributing to Truancy among students

One focuses on how economic factors affect students’ illegitimate absences from class, which is outlined as number one in the table. The literature review brought out the breakdown of the living circumstances. Students comprise fourteen percent of the population that resides with parents, twelve percent live without any parent, 67 percent live with just their mother, and six percent with just their father, Keppens & Spruyt. (2020).. In this case, it is not about parenting but the superiority of financial backers for the child that dictates the school attendance for the child. Supporting oneself or one’s family can cause stress and economic pressure; poverty can result in health problems and an absence of resources; overall lack of accessibility to amenities can increase absenteeism and health problems.

When focusing on the community factors, one may assume that the effect of its influence on Truancy is highly expected. However, these community factors only trigger the student-related variables of truancy behavior. The concept map also highlighted how student variables affect unreported absences from school. Substance/drug consumption, self-perception, and extenuating circumstances are three more categories into which these student characteristics might be subdivided. Twenty percent of all primary and secondary school students acknowledged consuming alcohol, with about fourteen percent saying they did so frequently—at least per month, Miller (2019). Fifty percent of the children who confessed to drinking alcohol skip class at least twice a month, compared to fifty percent who miss school less frequently. Drug use and neighborhood violence can exacerbate concerns about safety and mental health. Risk-taking behavior can also bring attention to problems, and peer pressure can lead to substance usage and a lack of interest in school.

The school environment, outlined in the table, may be the reason for Truancy. The dominant aspects surrounding the dilemma are the lack of resources, harmful policies, poor school attendance policies, and improper student placement. Many modest amounts of Truancy are linked to unfavorable outcomes like poorer academic performance, a higher likelihood of dropping out of school, and reduced potential for employment, Weathers et al.(2021). However, more significant amounts of Truancy have been shown to have much worse effects. From the data collected, more than half of the school population has been reported to be comfortable with the school environment where they find the company and establish their fundamental goal. However, one-third of the population of students are either forced or reinforced to attend school even though they are not comfortable with the school environment.

The results showed that the most critical factors influencing Truancy are those related to electronic media. Moreover, it was discovered that factors related to learners and their Truancy included those related to their families, themselves, their peers, and their educational surroundings. For instance, misuse of devices harms moral character (Chen, 2022). According to a study, this dramatically increases the likelihood that a teen will be absent from class, arrive late for educational institutions, and need help to obey the school’s regulations. Compared to typical electronic media use, the impact is more consistent with aberrant electronic media use. Even after accounting for absenteeism, using electronic media reduces the likelihood that a young person would continue their education after turning eighteen.

The findings showed that key contributing variables of Truancy include the teacher’s personality, pupil perceptions toward educational institutions, the environment in the classroom, the school administration, the instructors’ instruction, and the environment outside the classroom, peers, and families. For instance, harsh behavior, bad teaching strategies, a lack of cooperation, and poor communication encourage pupils to skip school. There proved to be strong positive relationships between all of the truancy-causing factors. The most significant association was found between instructors’ personalities and how they taught, while the most diminutive relationship was found between families and school management.

Educational disparity, school absenteeism, school attendance, and socioeconomic status Background and ramifications Justification for this study backed with literature regarding socioeconomic standing and school absence was synthesized narrative analysis. The discoveries are significant Socioeconomic gaps may be partially accounted for by differences in school absence.

The majority of studies discovered “positive” outcomes, such as that lower socioeconomic status was related to increased absenteeism rates; however, 29 percent of the studies had minimal impact sizes, of which twelve percent were tiny, 31 percent were moderate, 19 percent were medium-sized, and four percent were substantial. As a result, most research discovered ‘positive’ impacts considered at least marginal. Financial hardships can cause stress and mental health problems, insufficient access to healthcare can cause health problems that interfere with attendance, and unstable familial and domestic circumstances can cause family disputes and domestic violence.

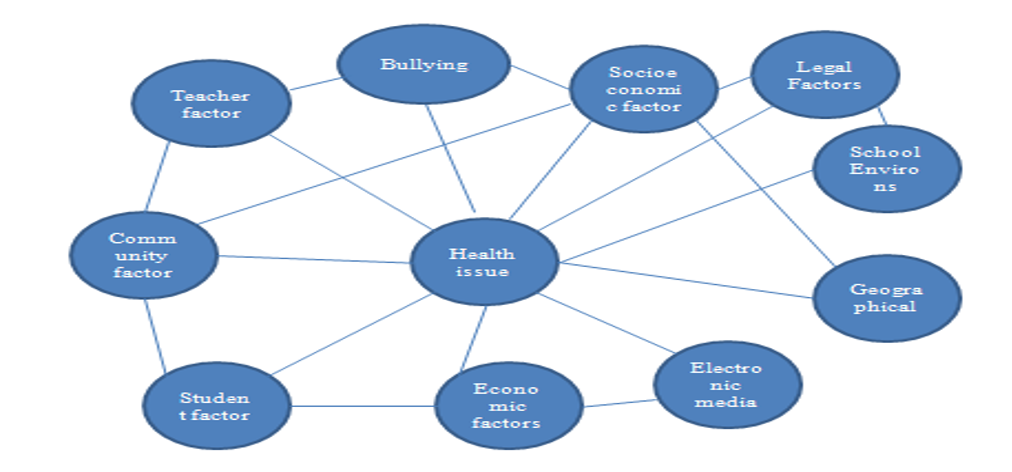

Interrelated Factors

Figure 2: Interrelated Factors

Minors must be transported to and from school each morning and on schedule by their parents or caregivers. Poor parenting abilities, a lack of ability to watch over kids, insecurity in the area, neglect and assault, encouragement to remain at the place of employment to support the household, and low regard for education are some ways a caregiver or parent can promote Truancy. The use of alcohol is strongly linked to student absenteeism. This discovery was consistent with the previously made in Swaziland (Gottfried, 2017). Gottfried (2017) also found a link between heavy alcohol use and frequent absences among 14- to teenagers in the UK. Health difficulties, whether personal or family-based, are also acknowledged as a significant factor in absenteeism among pupils because they prevent kids from going to classDespitete the fact that they should be noted, students frequently skip class when they are only mildly ill, even if doing would not prevent them from understanding the educational setting (Arbour et al., 2023).

Conclusion

Truancy has a negative impact on children’s academic, emotional, social, financial, and physical health. Truant children usually exhibit low academic performance and have less opportunity to continue their education, limiting their future opportunities (Arbour et al., 2023). There are social repercussions such as criminality and drug use because truant students are more likely to engage in risky behaviors and poor coping mechanisms. Truancy-related feelings of emotional loneliness and powerlessness can have psychological consequences like low self-worth, nervousness, and despair. The economic repercussions include fewer work opportunities, lower lifetime earnings, a higher chance of depending on welfare, and greater social costs due to greater rates of crime and decreased productivity. Truancy has a negative impact on health, increasing the likelihood of mental health issues, physical illness, and risky behavior.

The effects of Truancy on people, families, and society as a whole are far-reaching. Academic failure, pulling out, increased risk of illegal activity, and a lack of opportunity for upward social and economic advancement are all possible outcomes (Ali & Al-junior, 2023). Research shows that students who are frequently absent from school are likelier to fall behind in their studies, need help understanding concepts and material, and have lower grades (Eremie & Gideon, 2020). Substance misuse can increase attendance problems and challenges with mental health. Low self-worth can cause psychological problems and a shortage of motivation to attend school. Poor academic performance may result in apathy regarding schoolwork and mental health concerns.

Additionally, absenteeism may have serious societal and fiscal consequences, including but not limited to increased unemployment, destitution, high healthcare expenses, and an uptick in criminal activity and drug misuse (Aqeel & Rehna, 2020). The best way to combat absenteeism is to identify its reasons and work to eliminate them. Because of this, policymakers must adopt a comprehensive approach to Truancy, which involves both inside and outside-of-school activities and community-based initiatives that resolve the social and financial aspects that contribute to the absence (Kearse-McCastler, 2020). By including families and communities in the development and implementation of absence prevention projects, their effectiveness can be boosted.

References

Arbour, M., Soto, C., Alée, Y., Atwood, S., Muñoz, P., & Marzolo, M. (2023, January). Absenteeism prevention in preschools in Chile: Impact from a quasi-experimental evaluation of 2011–2017 Ministry of Education data. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 7, p. 975092). Frontiers Media SA.

Baskerville, D. (2019). Under the skin of Truancy in Aotearoa (New Zealand): A grounded theory study of young people’s perspectives. https://doi.org/10.26686/wgtn.17136134.v1

Baskerville, D. (2020). Truancy begins in class: Student perspectives of tenuous peer relationships. Pastoral Care in Education, 39(2), 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2020.1788125

Baskerville, D., & Loveridge, J. (2020). Nature of Truancy from the Perspectives of secondary students in New Zealand. Educational Studies, 49(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1834356

Chen, J. (2022). The effect of social network site usage on absenteeism and labor outcomes: longitudinal evidence. International Journal of Manpower. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijm-06-2021-0338

Gottfried, M. A. (2017). Does Truancy beget Truancy? Evidence from Elementary School. The Elementary School Journal, 118(1), 128–148. https://doi.org/10.1086/692938

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.975092/pdf

Keppens, G., & Spruyt, B. (2020). The impact of interventions to prevent Truancy: A research literature review. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 65, 100840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100840

LeClair, C. (2022). We are crew: School climate and culture at an expeditionary learning education school. AERA 2022. https://doi.org/10.3102/ip.22.1894000

Miller, F. (2019). School-based truancy courts. Encyclopedia of Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.1065

Ofori, K. N., & Yankyerah, A. K. (2022). Breaking the school-to-prison pipeline: A critical review of factors responsible for student’s Truancy. Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences, 141–156. https://doi.org/10.9734/arjass/2022/v18i330350

Ramberg, J., Brolin Låftman, S., Fransson, E., & Modin, B. (2018). School effectiveness and Truancy: A multilevel study of Upper Secondary Schools in Stockholm. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24(2), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2018.1503085

Roth, J. C., & Erbacher, T. A. (2021). Culturally Responsive School Mental Health Services and Education. Developing Comprehensive School Safety and Mental Health Programs, pp. 76–93. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003150510-7

Sorokin, O. (2022). Rethinking attitudes towards education in the cultural space of young people. Science. Culture. Society, 28(3), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.19181/nko.2022.28.3.8

Šuhajdová, I., & Gubricová, J. (2023). Analysis of conditions and factors influencing the incidence of Truancy in the school environment. INTED2023 Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.21125/inted.2023.0957

Virtanen, T., Pelkonen, J., & Kiuru, N. (2022). Reciprocal relationships between perceived supportive school climate and self-reported Truancy: A Longitudinal Study from grade 6 to grade 9. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2022.2042731

Weathers, E. S., Hollett, K. B., Mandel, Z. R., & Rickert, C. (2021). Absence unexcused: A systematic review on Truancy. Peabody Journal of Education, 96(5), 540–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956x.2021.1991696

Zhu, C. H., & Yu, L. Q. (2022). Analysis of causes and countermeasures of Secondary Vocational Students’ invisible Truancy. Computational Social Science, pp. 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003304791-25

write

write