The digestive system is a complex and coordinated system that breaks down food into its essential components and is responsible for nutrients in the bloodstream. Its functioning sustains life and provides the body with the necessary energy and resources for various physiological functions. The digestive system depends on the complementarity of structure (anatomy) and function (physiology) to accomplish its responsibilities. Digestive system organs possess outstanding structural adaptations that enable them to carry out particular functions effectively. The stomach’s sac-like structure stores and churn food, combining it with gastric juices with enzymes and hydrochloric acid for protein digestion. The muscular walls of the stomach allow it to contract and propel partially digested food to the small intestine. In the small intestine, the presence of villi and microvilli increases the surface area needs for absorption. The finger-like projections spread from the intestinal lining, optimizing contact with digested nutrients and expediting their absorption into the bloodstream. The gallbladder, pancreas, and liver produce substances and enzymes that assist in the digestion and emulsification of fats. Finally, the large intestine, with a wider diameter and higher capacity for water absorption, influences the reabsorption of water and electrolytes while forming feces for elimination. The rectum and anus provide take control of the removal process.

Organs and their Structure-Function Relationships

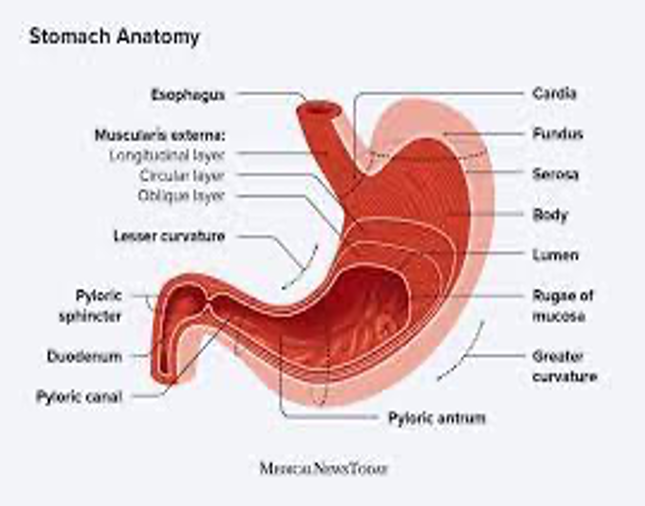

Stomach

The stomach exhibits a distinctive structure that supports its vital functions in the digestive system. It is a sac-like organ made of muscle tissue composition that enables it to contract and relax, generating powerful movements called peristalsis. The stomach reflexively breaks down food and bends it with gastric juices through peristalsis. The gastric glands in the stomach lining secrete gastric juices that comprise different enzymes and hydrochloric acid. Enzymes, like pepsin, play significant roles, such as initiating the breakdown of proteins into tinier peptide fragments. Hydrochloric acid develops an acidic atmosphere inside the stomach, which helps to activate enzymes and provide an optimal pH for protein digestion. The stomach’s muscular contractions and secretion of gastric juices enable chemical and mechanical food digestion, preparing it for more processing in the small intestine. The structure illustrates how the complementarity structure and function ensure the successful breakdown and initial food digestion in the digestive system.

Figure 1 illustrates the stomach’s structure and muscular layers (Sherrell, 2022).

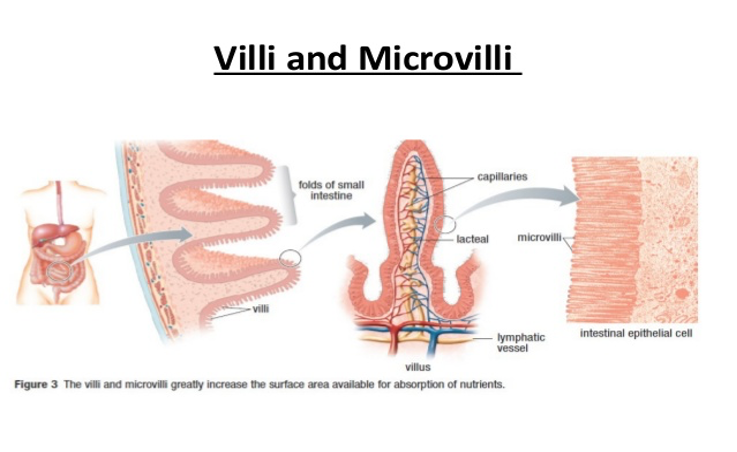

Small Intestine

The small intestine is a specially designed-digestive organ that enhances the digestive process. It is a long, coiled tube that helps absorb nutrients from digested food by creating an enormous surface area. Villi and micro-villi structures increase the already massive surface area. The small intestine’s lining is covered with projections called villi, which resemble fingers. These features create surface folds, which significantly increase the absorbent surface area. Each villus has its network of capillaries and lacteals, lymphatic and blood vessels. These capillaries are essential for bringing nutrients into the bloodstream and absorbing them. The microvilli, or “brush border,” are minute projections that may be seen on the surface of each cell that lines the villi. These minute hair-like structures further increase the small intestine’s absorptive potential. Thanks to the abundance of specific transport proteins in the microvilli, sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids can all be absorbed into the intestinal lining cells. Both villi and microvilli exist in the small intestine and show complementary structure and function. The small intestine’s particular structural adaptations greatly expand its surface area, allowing for rapid and complete absorption of food into the bloodstream.

Figure 2: The structure of villi and microvilli, highlighting their role in absorption (Abreu, S. (2017).

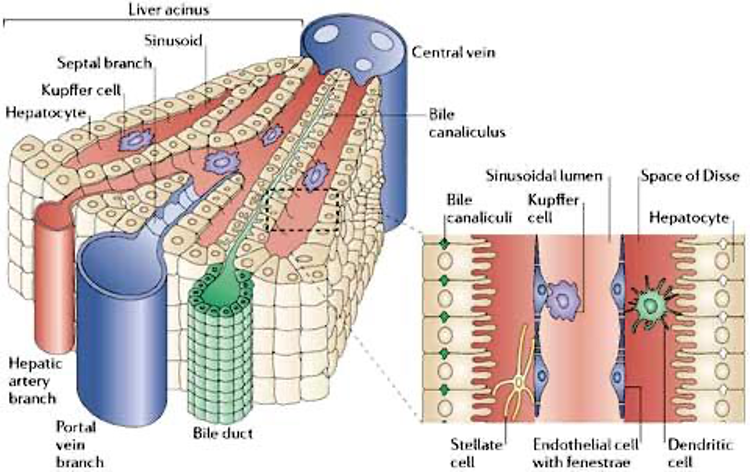

Liver

As the most significant internal organ, the liver constitutes a complex architecture of lobules, which are small functional units with specially arranged hepatocytes. The liver can perform its functions efficiently thanks to its intricate lobular structure. The liver generates bile, a greenish-yellow fluid, as one of its leading roles in digestion which aids in the emulsification and digestion of lipids. It is created by Hepatocytes and subsequently sent via a system of bile ducts to the gallbladder for storage and later released into the small intestine. Bile salts break down Huge fat globules into tiny droplets, increasing their surface area and making it possible for digestive enzymes to work on them (Wang et al., 2023). The arrangement of hepatocytes and the lobular structure of the liver facilitate sound bile generation and secretion, ensuring efficient fat digestion and absorption. The liver’s structure and function in the digestive system complement one another, underscoring this organ’s vital role in preserving overall digestive health.

Figure 3: Lobular structure of the liver (adapted from Cornell University College Of Veterinary Medicine, n.d.).

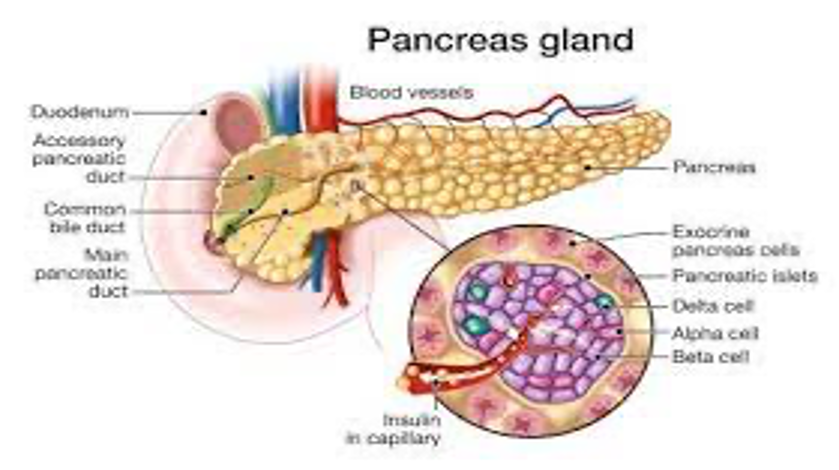

Pancreas

The pancreas serves both digestive, endocrine, and exocrine roles. Pancreatic acini are the structural building blocks of the pancreas. The small intestine depends on the acini to secrete digestion enzymes. The pancreas’ exocrine secretes pancreatic juice, a digestive enzyme-rich fluid. Amylase, lipid hydrolase, and protease are examples of synthesized and secreted enzymes. They facilitate the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins in the small intestine. Pancreatic acini layout and structure are optimized for the production and secretion of digesting enzymes. Pancreatic juice is secreted into the pancreatic ducts and carried to the small intestine with the facilitation of the proximity of acinar cells. The pancreas exemplifies how digestive organs work together due to their complementary structures and functions. The pancreas can perform its exocrine function, which includes the production and secretion of digestive enzymes enabled by the unique architecture of pancreatic acini.

Figure 4: The structure of the pancreas, including the arrangement of pancreatic acini (Rosenfeld, 2023).

Large Intestine

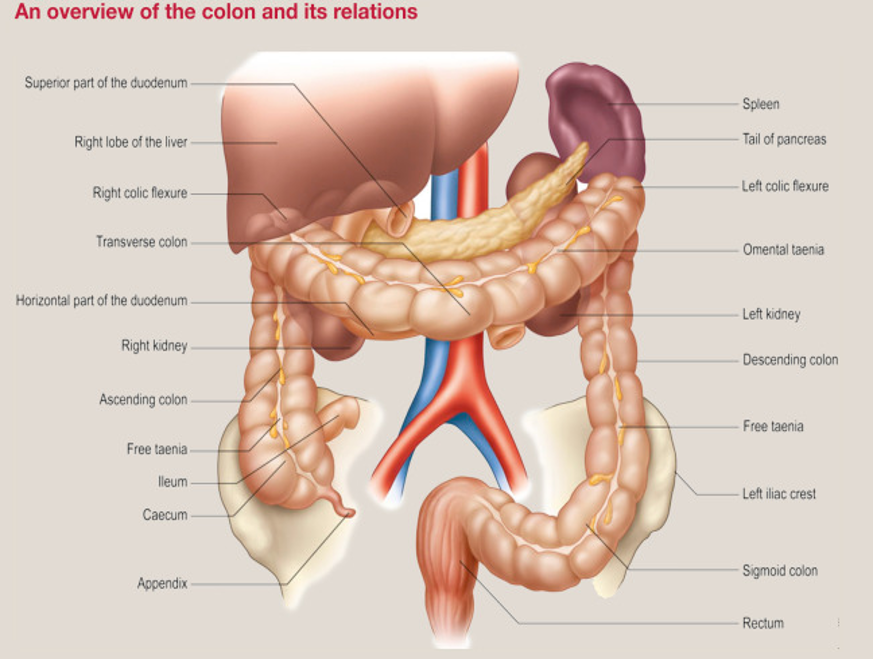

The structure of the colon, or big intestine, helps it perform its digestive roles. It differs in size from the small intestine, finalizes digestion, and excretes waste. The colon comprises a series of pouches called haustra, and muscle bands called taeniae coli contract that generate the haustra. Haustra enables the large intestine to expand and contract in discrete sections. The segmented structure assists in feces transit by mixing and pushing waste through the large intestine. Additionally, the large intestines are lined with three separated bands of smooth muscle known as taeniae coli. The muscle bands help create the haustra by providing structural support and stress. Constant contractions of the Taeniae coli produce a “milking” effect, which propels the waste material into the rectum for elimination. Besides carrying waste out of the body, the colon also absorbs fluids and minerals from the digested food. Its huge diameter and longer transit time allow for more water reabsorption helping the body to keep its fluid levels stable by reducing the amount of water lost in the stool. The unique architecture, including its haustra and taeniae coli, facilitates food digestion and water absorption. The large intestine is designed for digestion, waste removal, and fluid balance regulation.

Figure 5: Structure of the large intestine, highlighting the Haustra and Taeniae coli

Conclusion

The digestive system best demonstrates the interconnectedness between form and function. Each organ’s unique anatomical characteristics allow it to perform its physiological functions successfully. Food can be stored in the stomach’s sac-like structure, while the stomach’s muscular makeup facilitates food mixing and movement. Villi and microvilli in the small intestine improve the surface area for nutrition absorption. Due to its intricate lobular shape, the liver accomplishes various metabolic processes, including bile production. Through pancreatic acini, the pancreas secretes digestive enzymes. The big intestine’s distinct anatomy also helps with faeces production and water absorption. Understanding how the digestive system’s structure and function complement one another sheds light on its effectiveness and the general upkeep of our bodies’ equilibrium.

References

Abreu, S. (2017, May 29). How does the structure of villi allow efficient absorption in the small intestine? Socratic.org. https://socratic.org/questions/how-does-the-structure-of-villi-allow-efficient-absorption-in-the-small-intestin

Bazira, P. J. (2023). Undefined. Surgery (Oxford), 41(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpsur.2022.11.003

Https://study.com/academy/lesson/the-pancreas-structure-role-pathology.html. (n.d.). Structure of a liver lobule. eClinpath. https://eclinpath.com/chemistry/liver/liver-structure-and-function/liverlobule/

Rosenfeld, C. (2023). The Pancreas: Structure, Role & Pathology. Study.com. https://study.com/academy/lesson/the-pancreas-structure-role-pathology.html

Sherrell, Z. (2022, October 17). Cells of the stomach: Types, purpose, and location. Medical and health information. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/cells-of-the-stomach

Wang, Y., Wu, W. J., Zhang, T., Zhang, M. Z., Wu, Q. Q., Liu, K. Q., … & Wang, J. (2023). The digestive system. In Utero Pediatrics: Research & Practice (pp. 139-171). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

write

write