On June 17, 1882, Igor Stravinsky was born in Oranienbaum near St. Petersburg in Russia. Sergei Diaghilev, the director of the Ballets Russes, commissioned Stravinsky to arrange a few Chopin compositions for his ballet Les Sylphides in 1909. The Firebird, a collaboration with dancer Michel Fokine, was commissioned as a result, and when it premiered in Paris in June 1910, it made Stravinsky a household name. The performance of Petrouchka in 1911 cemented the composer’s reputation, as did the debut of The Rite of Spring in 1913, which sparked a riot but was subsequently praised for its revolutionary composition. Stravinsky moved with his family to Switzerland and subsequently France, where he composed works like Renard and Persephone. He had four creative periods; the Russian Period (c. 1907–1919), Neoclassical Period (c. 1920–1954), Serial Period (1954–1968), and Symphony in Eb (1907).

Musical style

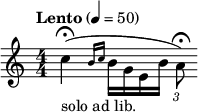

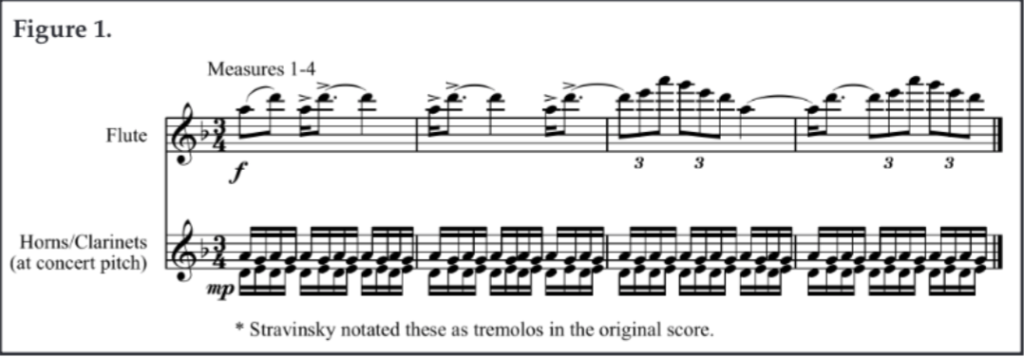

The rhythmic framework of the ‘Rite of Spring’ is the most striking and visible aspect of its full distinctiveness. Stravinsky pushes the boundaries of harmonic structure, drawing on Petrushka’s tactics of constantly varying rhythms and odd meters.1 Separate orchestral parts frequently play opposing and clashing beats, much like an extended hemiola that isn’t bound to the juxtaposition of three over two. All instruments share the available time signature of 2/4 for at least one measure. The unusual syncopated rhythms, on the other hand, destroy any feeling of rhythmic continuity throughout sections, albeit in a wonderful and realized fashion. However, as can be noticed from the beginning, the general time signature shifts from measure to measure, starting in 4/4 and moving to 3/4 for the second measure, then returning to 4/4 and then to 2/4.

- Henry “Igor Stravinsky.” The Musical Times (2019): 268.

The emergence of quintuplets, sextuplets, triplets, and septuplets instantaneously superimposed on each other occurs in almost every standard of measurement of the first two pages of the score (up to Rehearsal 5), at which point the meter potentially maintains its 2/4 identity but is further overthrown by the emergence of sextuplets, quadruplets, and triplets simultaneously superimposed on each other. Furthermore, the musicians are put under even more strain by the high-speed, non-coinciding runs of 10 pitches in one beat (well exemplified in the quintuplets of every measure of Rehearsal 9 and 6 of Rehearsal 8)

In ‘Rite of Spring,’ Stravinsky stresses unexpected placements in measures, thus weakening any regular or predicted rhythmic flow. Part I, “Dances of the Young Girls” (page 12, Rehearsal 13), for example, has a rather basic rhythm at beginning, with consecutive 8th note doubled pauses in each of the four instrumental passages. When French Horns accompany the offbeat on the ends of beats 1 and 2, denoted with sforzandos, Stravinsky underlines the unexpected. Other instruments with accents at the ends of beats 1 and 2 have the same asymmetrical emphasis.2

Thus, in addition to noting accents in the score, Stravinsky uses orchestral techniques to emphasize and draw attention to previously apparent syncopations This method (aided by the orchestra’s overall strong percussive quality) is used throughout the composition, with powerful instruments introduced and spotlighted on rhythmic offbeats.

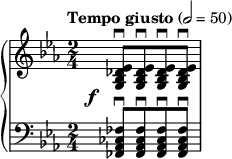

Though Stravinsky’s rhythmic methods may be explored indefinitely, the Rite of Spring’s prominence is also due to its melodic structure and extreme dissonant chords and discord. For example, all of the instruments vibrate a single chord at the start of “Dances of the Young Girls”

- Henry “Igor Stravinsky.” The Musical Times (2019): 68.

From the beginning, this chord is incredibly discordant. It has an F-flat dominant triad as well as an E-flat minor triad. The 7th chord is dominant. As a result, it can be regarded of as being formed from an octatonic pitch as well. It comprises the notes E, G, A-flat, B-flat, and D-flat, all of which are part of the E-flat octatonic scale. At Rehearsal 13, this “chord” is made up of E-flat, D-flat, B-flat, E, F-flat, and A-flat.3

- The Adoration of the Earth

A solitary clarinet plays the opening theme in an extraordinarily high register, rendering the instrument virtually unidentifiable; more woodwind instruments gradually join in, and strings are finally introduced. The sound intensifies before abruptly ceasing. There is a reassertion of the initial bassoon solo, now played a semitone lower, just as it explodes euphorically into blossom.4

- Fuller-Maitland “Grove’s Dictionary.” Music & Letters 9, no. 2 (2018): 97.

- Henry “Igor Stravinsky.” The Musical Times (2019): 268.

The opening dance, “Augurs of Spring,” features a pounding harmonic in the strings and horns based on an E dominant seven superimposed on an E, G, and B triad. On and off the beat, Stravinsky’s frequent changing of the accent disrupts the stomping rhythm before the dance finishes in a collapse, as if from tiredness.

- The Sacrifice (1959)

The music follows a curved path from the commencement of the Prologue to the end of the latest dance. The Introduction features a lot of woodwinds and subdued trumpets, and it closes with a lot of ascending melodic lines on strings and flutes. The shift into “Mystic Circles” is practically subtle; the section’s principal theme is foreshadowed in the Introduction.5 The period for choosing the intended victim is announced by a loud, recurring note. The “Evocation of the Ancestors” that follows the “Glorification of the Chosen One” is rapid and aggressive,

- Fuller-Maitland “Grove’s Dictionary.” Music & Letters 9, no. 2 (2018): 78

With short phrases interspersed with drum rolls. The “Ritual Action of the Ancestors” begins gently, then develops to a succession of climaxes before abruptly returning to the quiet sentences that started the episode.

The Russian folk dialect that runs throughout the music of ballet (and choreography) is also notable. This can be seen in the brief, straightforward melodic segments combined with other fragments to form more significant, more complicated components. The fragments, albeit simple, are harmonic and frequently result from the scalar linkage of chords in lower rhythm. Stravinsky, for example, reshuffles the notes of F-G-A-flat-B-flat to form a melodic strings of lines in Rehearsal 19 of “Dances of the Young Girls.”

Stravinsky first delivers a series of four separate short rhythmic segments in measures 5- 11 of Rehearsal 28 and then replays the four segments six times, although in a reverse context each time. A more harmonious whole is formed using a unique framework of repeated chaotic melodic pieces. The piece’s rhythms, particularly in terms of its ostinato features, reflect this unique approach to melody and its ostinato placing.

Stravinsky appears to move away from self-aggrandizing renown in works like the Symphony of Psalms (1930), Requiem Canticles (1966), and Threni (1957). He sets several psalm verses as solemn prayers in the Symphony of Psalms. 6 The second movement is based on the popular U2 song 40 (1983), which uses the same material (Psalm 40 in Protestant Bibles and Psalm 39 in Eastern Orthodox numbering).

- Fuller-Maitland “Grove’s Dictionary.” Music & Letters 9, no. 2 (2018): 18

- Symphony of Psalms (December 13, 1930)

I patiently awaited the Lord’s response; he bowed and heard my cries.

He dragged me out of the abyss, out of the muck.

My feet were planted firmly on a rock, and my stride were steady.

He taught me a new hymn, a song of worship to our God

Many will see and be afraid, but they will put their faith in the Lord. 47.

- The Joshua Tree (March 9, 1987)

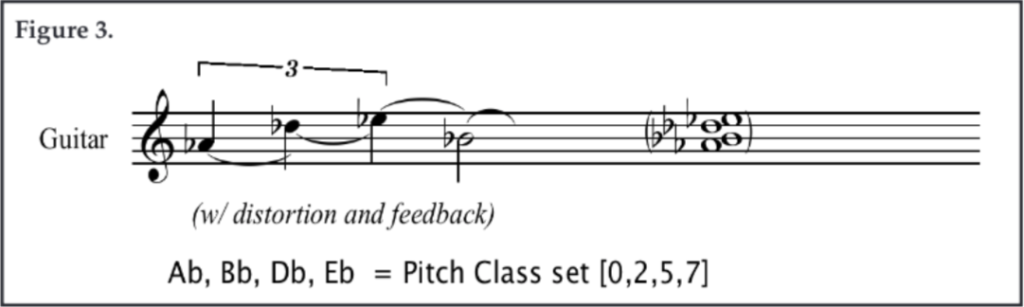

In The Joshua Tree, static textures play a vital part as well. The introduction of Where the Streets Have No Name is a good illustration of this. The song’s opening could be described as “tones through the statement,” instead of advancement, by a theorist. The song’s buzzing, distorted guitar riff develops associations between particular tones that remain consistent throughout. Although there are chord changes in the piece, they generate a very sluggish harmonic beat supported by stable pedal notes in both the lower and higher registers. This produces a sense of stability to the audience and reduces the importance of melodic progression in the musical substance.

- Storm Clouds (April 10, 1930)

In his early ballets, Stravinsky’s rhythmic and poetic palette is built on unique symphonic instrument combinations and applications. Apart from all theoretical assumptions that it manifests, Stravinsky’s music is also intriguing because of the direct, objective exploration of essential harmonic qualities and correlations, which is especially apparent in his utilization of heretofore overlooked periods, such as the second. His songs have gained a nuance of tonal finesse through this exploitation of the more acute intervals, giving his tonal coloring a broadness, abundance, and mosaic uniqueness, a total combined force of appeal and importance and making it a more exact mode for the emotional state than any other yet unearthed. From a strictly musical standpoint, Stravinsky’s style has incalculably increased the store of musical materials, but at the same time.

His modulation technique is independent of any modular durations or chord key connections. Other aspects of his technique reveal a proper psychological understanding. Stravinsky’s tonal writing has been expanded so that it has generated a correspondingly wide and multiple channels of affirmation. He recognizes that no emotional reaction today is simple but almost inevitably comprises mental emotion, owing to the diversity of modern facets and connections. 7 Thus, Stravinsky transformed the earlier writing on a pedal, a defining trait of the neo-Russian group, into a harmonic pedal group, which could be utilized alone on any level of the melodic parts or in a group.

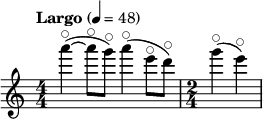

Stravinsky’s use of diverse instrumentation to produce different orchestras of sound is a major trait of Symphonies of Wind Instruments.8 These groups are frequently at odds with one another and seldom cross paths. Another key aspect of the song is the pace. When employing varied meters, Stravinsky uses three main tempos (basically quarter note = 72, 108, and 144), constantly retaining the eighth-note rhythm inside each of them. These frequently shift rapidly, yet they are linked by the 2:3:4 ratio, making them simple to reproduce precisely as Stravinsky requests. Both the orchestration and tempo portions frequently terminate rapidly and without changeover, resulting in a form of blocks that is common in Stravinsky’s work.

- Fuller-Maitland “Grove’s Dictionary.” Music & Letters 9, no. 2 (2018): 97.

- Henry “Igor Stravinsky.” The Musical Times (2019): 268.

Changes in instrumentation and pace, on the other hand, convey hints. The composition is broken into two halves, which were separated at session 42. Before that, Stravinsky presents six melodic blocks and three different types of change-over, all of which are flipped around and presented in various orders, never merging until for a larger changeover passage at rehearsal 11. Only two of those blocks, as well as a new transition type, are treated after 42, with the last harmonic progression block taking up the majority of the second half. As a result, Symphonies of Wind Instruments moves from action and diversity to immobility and uniformity. Stravinsky employs at minimum 37 different instrument combinations throughout the process.

Conclusion

The distinction between Stravinsky’s work and the rhythmic and thematic content of older artists’ work can be loosely described as comparable. Stravinsky’s musical features stem from his realistic awareness, which is concerned primarily with vital realities and their appropriate and accurate assimilation into musical representation.

Bibliography

Henry, Leigh. “Igor Stravinsky.” The Musical Times (1919): 268.

Fuller-Maitland, John Alexander, Grove, George, Pratt, Waldo Selden. “Grove’s Dictionary.” Music & Letters 9, no. 2 (2018): 97.

write

write