Introduction

Beijing Trilogy is a series of three films directed by Ning Ying, featuring three generations of Beijing civilians. Looking For Fun (1993) depicts the story of Old Han setting up a Peking Opera club with other retirees. On The Beat (1995) tells the story of a police officer, Yang, catching mad dogs in the area of his jurisdiction. I Love Beijing (2001) narrates the story of taxi driver Dezi, who looks for true love while picking up passengers. Moreover, the Beijing Trilogy spans the entire 1990s, which was the decade of the rapid development of China’s urbanization. During this period, Beijing underwent irreversible and significant transformations in its urban landscape, individual value system, and social structures. This article analyzes three dimensions of city space in the Beijing Trilogy, examining the impact of Beijing’s urban spatial changes and social transformation on the lives of civilians in China’s post-socialist era.

Literature Review

Although Ning Ying belongs to the fifth generation of Chinese directors, the number of studies on Ning Ying’s films in China and around the globe is far less than those of Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige of the same generation. As Cui Shuqin argues, most of the fifth-generation directors focus on national allegories and visual splendor, like Raise The Red Lantern (Zhang Yimou, 1991) or Master Of The Crimson Armor (Chen Kaige, 2005), while Ning Ying does not (Cui 2007, 242). Her films are more likely to use documentary techniques and narratives without strong plots, restoring the realistic image of Beijing in the 1990s.

Some scholars study Ning Ying’s films from the perspective of feminism based on her gender (Wang 2011; Xiao 2014). This may be suitable for her later film Perpetual Motion (2005) but not for her Beijing Trilogy. As Cui Shuqin argues, “Although Ning is an important female director, her camera frames urban milieu through the male protagonist’s perspective in her early films.” (Cui 2007, 242). In Beijing Trilogy, Ning Ying consciously documents the changing and developing urban spaces of Beijing and aims to preserve them through the medium of film. However, previous research has yet to study her films from the perspective of urban space.

“If you are observant, nothing is trivial.” This is one famous line from the film Lust, Caution (Ang Lee, 2007), and it can also explain why the Beijing Trilogy is a suitable archive for studying the post-socialist era in China. The trivial details of everyday life for citizens and the urban spaces of Beijing form the basis of these three films, making the Beijing Trilogy seem like a random collection of documentary-like segments. However, Ning Ying once mentioned in an interview, “Someone told me that your films simply show a lot of things like a documentary, but they don’t address any social issues. This is the greatest compliment to me, as it proves that when watching these films, they have forgotten that I carefully selected every detail.”(Shen, 1996) While seemingly depicting ordinary daily life, every choice made by the characters is intricately linked to the backdrop of the post-socialist era. By uncovering the designs hidden within the spaces and moving images, one can discern the profound effects of social transformation during the post-socialist period on Beijing citizens.

The theoretical basis of this article is post-socialism. American left-wing scholar Arif Dirlik uses the concept of “post-socialism” to study the socialist practice with Chinese characteristics, analyzing the period after China’s reform and opening up in 1978 when it abandoned the centralized planned economy and moved towards a market economy. In his view, this concept encompasses political transformation, economic reform, and the continuous formation of civil society (Dirlik & Meisner, 1989). Paul G. Pickowicz uses the concept of “post-socialism” to study the fifth-generation director Huang Jianxin’s urban films from the 1980s to 1990s (1994). He points out that post-socialism can capture the distinctiveness and complexity of Chinese urban life in the 1980s and 1990s. Post-socialism refers to the initial stage of socialism and enters the stage of social transformation. The prevailing dystopian cultural conditions in society lead people into confusion (Paul 1994).

The theoretical framework of this article is spatial analysis. Since the publication of Henri Lefebvre’s “The Production of Space,” the academic community has embarked on a new direction of social critique, reexamining societal issues through a critical perspective on space (1974). Then, Swiss German scholar Christian Schmid interprets Lefebvre’s concept of urban space as three dimensions: physical, mental, and social (2005). Physical space refers to the natural and worldly geographical environment. Mental space represents the symbolic and formalized abstract realm of the mind. Social space is the space related to social structures, encompassing both people and the environment (Schmid 2005, 209-210). The three dimensions of urban space are interrelated. Physical space is the tangible and experiential space. Mental space is produced from physical space and is conceptual or fictitious. Social space encompasses both physical space and mental space so that it can be both concrete and abstract (Christian Schmid, 2005). In Ning Ying’s Beijing Trilogy, the most striking aspect is not the narrative itself but rather the visual depiction of Beijing’s urban spaces. Therefore, the article analyzes three dimensions of urban space in the Beijing Trilogy, which reveals the postsocialist era of Beijing during the 1990s.

Physical Space: The Demolition and Construction of Urban Landscape

In Beijing Trilogy, the most striking feature of Beijing’s physical space in the 1990s is the constant demolition of courtyards and ancient buildings as well as the continuous construction of high-rise buildings. The urban landscape of Beijing in the post-socialist era became increasingly modern. Still, the distance between the residents and the city increased, which gave the civilians a sense of loss and loneliness.

After the reform and opening up, China entered the post-socialist society and transitioned from a planned economy to a market economy. The process of urbanization accelerated, the urban population increased, and the Beijing government initiated a re-planning of the urban areas, aiming for the development of Beijing as an international metropolis. Beijing Trilogy, spanning from 1993 to 2001, captured the changes in the urban landscape through visual imagery. These three films all begin with Beijing street scenes, but they differ in terms of filming perspectives and scenes, representing different ways of observing Beijing by three generations.

In Looking For Fun, the street scenes are captured in full shots, with low-angle and eye-level perspectives. There is a significant presence of bicycles and a few cars on the city roads (see Figure 1). The camera movement simulates the walking speed of Old Han, which shows a close connection between the city and the character. Old Han feels a close connection to the city.

Figure.1 Beijing’s traffic in 1993

Figure.2 The crane is demolishing the traditional buildings

At the same time, Beijing is undergoing the beginning stages of demolition and construction. Due to the urbanization process, senior citizens of Beijing, such as Old Han, witnessed the constant demolition of courtyards, hutongs, and other ancient Chinese buildings in the 1990s to make way for high-rises. In Looking For Fun, there is a long shot of Old Han’s traditional residence with a crane standing behind it (see Figure 2). With the continuous demolition of traditional buildings, the physical space for senior citizens’ lives in the city is shrinking.

Figure 3 Beijing’s urban landscape in 1995

Figure.4 Police ride through the residential area

In On The Beat, it can be seen that more courtyards have been extensively demolished. The residents who used to live in the courtyard have moved into high-rises. Through the conversation between Yang and his police colleagues, it is revealed that in the residential area under Yang’s jurisdiction alone, over 700 courtyards have been demolished. In the high-angle and long-shot scenes, the high-rises in the distance are constantly encroaching upon the courtyards (see Figure 3). Yang and his colleagues ride bicycles, navigating through the desolate and bustling urban landscape, maintaining a certain distance and discretion in their relationship with Beijing, sometimes feeling close and sometimes distant (see Figure 4).

In I Love Beijing (2001), Beijing’s courtyards and traditional buildings have been demolished even more thoroughly, and high-rise buildings dominate the cityscape. The first shot in I Love Beijing is a highly long shot from a bird’s-eye view (see Figure 5). The wide roads, bustling crowds, and continuous flow of vehicles in the frame depict Beijing as a modern city stepping into the 21st century. As the camera continues to zoom in, busy intersections filled with cars and towering buildings lining the streets come into view (see Figure 6).

Figure.5 Beijing’s traffic in 2001

Figure.6 Beijing’s urban landscape in 2001

Faced with the rapid modernization of the city, a faster way of understanding urban space is needed, and cars are the perfect choice. The protagonist of I Love Beijing, taxi driver Dezi, navigates the streets of the city all day long. The camera’s movement in capturing the street scenes also simulates Dezi’s way of observing the city from inside the car. In comparison to the walking of senior citizens and the cycling of middle-aged citizens, observing the city from the enclosed space of a car allows for a more incredible view of the urban landscape. Still, it also creates a greater distance from Beijing and a less sense of belonging to the city.

In the post-socialist era, China experiences a transition of physical space in its cities. Within less than a decade, the urban landscape of Beijing undergoes rapid changes in the Beijing Trilogy. Traditional buildings are demolished, and high-rises emerge rapidly. Beijing has become increasingly modern and trendy, but the civilians of Beijing gradually feel estranged from the city they once knew and loved.

Mental Space: The Collapse of Individual Value System in the Blue Rain

When people equate their lived experiences and perceived spaces with conceptualized spaces, the concept of space tends to become a system of signs. Therefore, by interpreting the text of the physical space, the objective reality of space is transformed into an imaginative and symbolic mental space (Schmid 2005, 38-39). At this point, space becomes a metaphor that participates in the narrative of the film. In Chinese culture, rain carries the imagery of tears and is associated with a melancholic mental space in Chinese literature (Yeh, 1987). In the Beijing Trilogy, each film includes a rainy scene where can be observed a common theme of conflicting values, the protagonist always experiences a loss of power and a collapse of values within the rainy space.

In Looking For Fun, the rain occurs when Old Han is searching for an indoor venue for Beijing Opera amateurs. He stands in the rain outside a ballroom dance activity station, watching people dance through the window. The scene is divided into two parts: on one side, the bright and warm indoor space symbolizes the higher discourse power of the community, while on the other side, Old Han is all wet and stands alone in the dark, and the rain makes him look even more pathetic and lonely (see Figure 7). In the postsocialist era, collectivism is challenged by individualism, and senior citizens like Old Han, who have experienced the high collectivism of the primary socialist stage, cling to traditional socialist values and continually seek a community to join.

Figure 7 Old Han looks at people dancing ballroom dance.

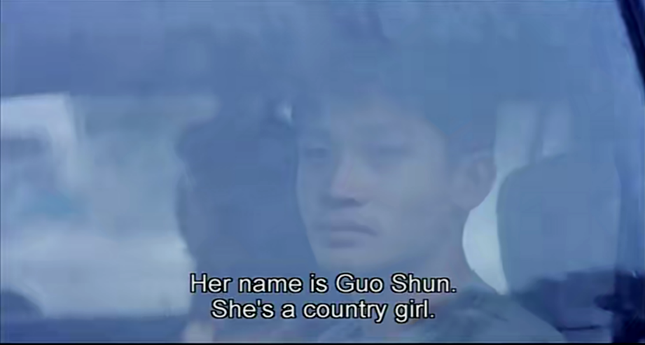

In On The Beat, Yang and his colleagues apprehend a dog hidden by a family. When the police officers find the hidden dog and capture it, the child in the family cries sadly. The police officers seemingly transform from righteous heroes into villains in that condition. Inside the police car on their way back to the police station, the heavy rain outside cast a blue, cool-toned light into the vehicle, giving the space a chilly and gloomy atmosphere (see Figure 8). The police officers and the dog remain quiet on both sides of the car, while the sound of rain outside further accentuates this silence. The contrast between the police officers and the dog is depicted in this scene, with the dog trapped in a cage and the police officers trapped in the conflict between personal values and the system. In the post-socialist era’s transition from a society governed by individuals to a society governed by the rule of law, the police transformed from protectors loved by the people to agents of state violence. They also face oppression from the system, becoming increasingly instrumental zed and objectified. Their faith in the police institution and the government is gradually collapsing, leading them into confusion.

Figure.8 Police officers are smoking silently

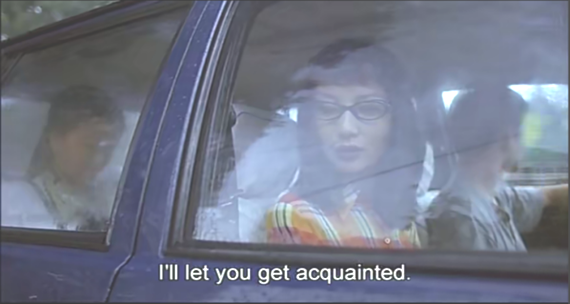

In I Love Beijing, taxi driver Dezi has a romantic relationship with Zhao, who dreams of making big money and immigrating to the United States. However, their love, characterized by Dezi’s romantic ideals and contentment with the status quo, is destined to be short-lived. On a rainy day, Zhao introduces a country girl named Guoshun to Dezi and then breaks up with him (see Figure 9). In this scene, Dezi and Zhao sit on opposite sides of the car, representing traditional notions of love versus consumerism. In the post-socialist era, traditional notions of love are challenged by consumerism, and some people place more value on commodities than on human relationships. Dezi’s stable job and upright character are no longer desirable in Beijing’s dating market. The camera, filmed from outside the car, captures Dezi behind the rainy window, watching Zhao’s fading figure with reluctance, as if there were tears on his face. The rainy space helps the characters in the film express their inner emotions. Compared to crying directly, this expression is more subtle and in line with Dezi’s rough exterior and sensitive inner character.

Figure 9 Zhao dumps Dezi.

From Looking For Fun to I Love Beijing, the camera gradually distances itself from the characters. In I Love Beijing, the character and the camera are consistently separated by car windows, symbolizing their increasing sense of isolation and loneliness. The rain makes Beijing appear blurry, and the familiar things and beliefs of Beijing civilians begin to change, and their value systems are crumbling in the rain.

Social Space: Individuals Squeezed out from Circles under the Changing Social Structure

China entered the postsocialist era in the 1990s, with the market economy challenging the planned economy, society transitioned from being ruled by the party to a modern rule of law, and traditional culture was challenged by Western culture (Chen, 2020). These lead to class differentiation and significant changes in the social structure, while Beijing civilians are squeezed out of the community and experience a postsocialist dystopia.

On the cultural level, one of the most representative aspects of Beijing’s traditional culture, Peking Opera, is similar to Old Han, which becomes marginalized and enters its old age under the pressure of popular and Western cultures. However, the retired Peking Opera amateurs, despite being a marginal cultural circle, Old Han still cannot squeeze in. Old Han joins this circle, aiming to find the social status and personal value he lost in his workplace and revive the collectivism of the early-stage socialist era. At the same time, other senior citizens are merely looking for fun. Therefore, other retired amateurs are dissatisfied with the numerous rules and regulations set by Old Han, leading to his exclusion. At the end of Looking for Fun, the retired amateurs gather in their usual circle to sing Beijing opera while Old Han sits alone in the distance, wondering whether to make peace actively (see Figure 10). As a solitary retired individual, there are no other circles in society that can accept him, forcing him to set aside his pride and request to rejoin the circle that once excluded him (see Figure 11). The problematic situation faced by the elderly in the post-socialist era is quite apparent.

Figures 10 &11 Old Han finally decides to put his pride aside and return to the community.

On the political level, during the post-socialist era of the 1990s, policy adjustments and the realignment of government functions failed to keep pace with social development. Police, as the focus of social contradictions, were the first to feel the pain of being institutionalized as repressive state apparatuses (Chen 2020). At the end of the film, Yang follows the instructions of the commissioner and interrogates Wang, who refuses to hand in his dog. When Wang says, “Police are mad dogs,” he prompts Yang to hit him.

As a middle-aged police officer with Confucian morality and strong identification with the institution, Yang gradually realizes the less honorable aspects of the police force in the post-socialist era. On one hand, the police sacrifice themselves for the government and perform tedious tasks, even losing their time. On the other hand, when facing citizens, the police become members of the state apparatuses, merely executing orders and being completely objectifiedTheat The beginning and the ending of On The Beat can be observed in the same scene of a police meeting, where Yang has moved from sitting next to the commissioner to a distant seat, indicating his demotion (see Figures 12&13). In the postso era of social transition, individuals like Yang, who struggle between institutional obstacles and humanitarianism, become sacrifices of an imperfect political system, squeezed out by the circle of the system and mechanisms.

Figure.12 Yang sits next to the commissioner at the beginning

Figure.13 Yang sits far away at the end

On the economic and class level, during the rapid urbanization of postsocialist Beijing, love relationships among civilians also face the impact of money, and the social structure is shaping. Dezi, a naive Beijinger, ultimately chooses to marry Guo, a country folk from another province. Guo represents a large number of people from other provinces who arrived in Beijing in the 1990s. They work tirelessly to establish themselves in Beijing, even resorting to marriage. When Dezi breaks up with Zhao, they sit in the front seat of the car while Guo sits in the back seat, symbolizing their respective class positions (see Figure 14). As a nati e of Beijing, Dezi and Zhao have a higher social status than Guo, who represents outsiders. Later, Zh o gets out of the car and moves forward to pursue a better life, leaving Dezi and Guo in the same space. Due to money and social status, different women from different social classes make different choices.

Figure 14 Dezi and Zhao sit in the front while Guo sits in the back.

In I Love Beijing, Dezi constantly experiences breakups, and his final breakup is with the city of Beijing itself. One night, after getting drunk and being expelled from the Maxim Western Restaurant, Dezi’s self-esteem is shattered. In the 1980s, being a taxi driver in Beijing was a prestigious profession, and taxi drivers were considered part of the upper class. However, within less than a decade, they gradually fell from grace. Being dumped by Beijing native girls and being expelled from high-end establishments, Dezi feels the same heartbreak as breaking up with girls he had relationships with. He stops the car, leans over by the roadside, and vomits. Then, he cried for the first and only time in the film (see Figure 15). Indi is facing the city he loves, rapidly developing and changing, and realizes that no matter how hard he tries, he cannot keep up. Dezi is squeezed out of all circles; he becomes an exile from the whole city. Under the changing social structure, Dezi, as a native Beijing civilian, gradually discovers that he is quickly falling into the lower class, and the outcome awaiting him is the increasing difficulty of making money and being forced to marry Guoshun, who is from outside Beijing.

Old Han, Yang, and Dezi represent the actual situation of the ordinary civilian class in postsocialist Beijing. A minor issue in the era can feel overwhelming to an ordinary individual. Face with the societal transformation of postsocialist dystopia, civilians without the ability to cope can only silently endure their ordinary daily lives. Instead of focusing on people who adapt to the rapid development of the times, Ning Ying demonstrates her humanistic concern for vulnerable groups and their dilemmas.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Beijing Trilogy depicts the struggles and confusion experienced by different generations amid the dystopia of social transformation in the postsocialist era, using urban spaces as visual representations. While Beijing’s urban landscape, individual value system, and social structure have all undergone changes nowadays, the situation of native Beijing civilians remains far from optimistic. From the 1990s until now, part of the native Beijing civilians have deteriorated to become the poorest group in Beijing, falling into the lowest-middle class of society. The solution to the predicament faced by Beijing civilians remains an unsolved puzzle. Beij ng Trilogy also touches upon marriage and gender relations in the post-socialist era, which couldn’t be covered in this article due to length limitations. Futu e research on Beijing Trilogy and even studies on the films reflecting the post-socialist era in China will delve deeper into these issues.

References

Chen, Tao. (202 ). Watc ing movies through the city: the spatial production and motion sensing of Chinese contemporary images. Beijng: Tsinghua University Press.

Cui, Shuqin. (2007). Ning Ying’s Beijing trilogy Cinematic Configurations of Age, Class, and Sexuality. In The Urban Generation Chinese Cinema and Society at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century (pp. 241-263). North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Dirlik, A., & Meisner, M. J. (Eds.). (1989). Reflections on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. In Marxism and the Chinese experience: Issues in contemporary Chinese socialism(pp.231-384). Lond n: Routledge.

Fromm, Erich. (194 ). Esca e From Freedom. New York: Macmillan.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Lond n: Blackwell.

Lian, Yixuan. (2021). Perspective and expression: a study on the realistic characteristics of Ning Ying’s films (MA thesis). Shaa xi Normal University, China.

Pickowicz, Paul.G. (1994).Huang Jianxin and the Notion of Postsocialism. In, New Chinese Cinemas: Forms, Identities, Politics (pp.59-63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schmid, C. (2005). Stadt, Raum und Gesellschaft: Henri Lefebvre und die Theorie der Produktion des Raumes (Vol. 1). Franz Steiner Verlag.

Shen, Yun. (199 ). An Interview with Ning Ying About Looking For Fun and On The Beat. Contemporary Cinema, 3, 35-36.

Wang, L. (Ed.). (201 ). Chin se women’s cinema: transnational contexts. Colu bia University Press.

White, J. (1997). Film of Ning Ying: China unfolding in miniature. Cineaction, (42), 2-9.

Xiao, H. F. (2011). Inte iorized feminism and gendered nostalgia of the ‘daughter generation’in Ning Ying’s Perpetual Motion. Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 5(3), 253-268.

Xu, Keke & Shen, Zhongyu. (2024). A Space Study of Chinese Realistic Film in the New Era. Radi & TV Journal, 1, 38-41.

Yeh, M. (1987). Circularity: Emergence of a Form in Modern Chinese Poetry. Mode n Chinese Literature, 33-46.

write

write